On Collective Documentary Practices: Ektara Collective’s Ek Jagah Apni

As explored in our brief survey of collective filmmaking practices earlier, a shade of authoritative filmmaking survived into the 1980s in the work of groups like the Odessa Collective. However, that decade in India also started registering a turn away from such practices. Minoritarian political groups entered the fray and instituted more radical features into the very modes of producing new films on collective action, even as funding bodies for such exercises began to run dry. These changes were also signalled globally, especially through the rise of alternative feminist filmmaking collectives. Rachel Pronger suggests that “(c)reeping neo-liberal ideology and new funding structures began to incentivise individual over collective making, while schisms within the second wave feminist movement started to fracture the networks of artist, activist, and community groups that had fed the movement.”

It is not a surprise, therefore, that Ektara Collective’s recent film Ek Jagah Apni (A Place of Our Own, 2022) resurrects debates around filmmaking collectives at the level of decentralised production as well as at an allegorical level, where the collectivist spirit leaves a mark on the narrative of the film.

This could very well be an alternative model of the collective experience in filmmaking as a transmuted form of film watching. This is the direction in which the Left Humanist People’s Film Collective in Kolkata has oriented itself, for instance, as it tries to mould a film audience into a politically conscious community. To create such communities, especially in times of extreme political and social marginality for resistance movements, is surely necessary. But the latter differs from the Odessa Collective by exorcising the ghost of the auteur as “Hitler.” And it is largely this strand of its legacy that animates other filmmaking collectives in India today, such as the Ektara Collective or the transnational Nama Filmcollective, whose new film was also screened at the Kolkata People’s Film Festival 2023.

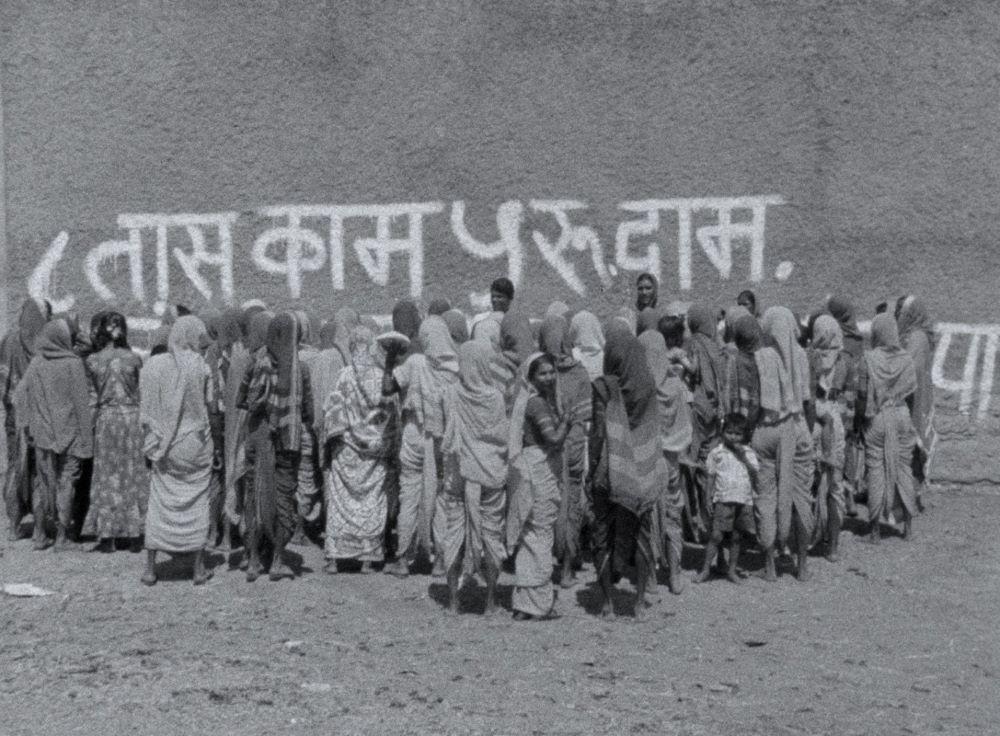

Instead of the Odessa Collective, therefore, one may find echoes of a similar practice in other collectives formed around the same time. For instance, the radical feminist filmmaking collective Yugantar, which was active between 1980 and 1983. They made four films that embraced collective decision-making in every aspect of production. This ranged from the politics of representing working women on camera to employing an aesthetic that communicated their concerns directly, even if it subverted aesthetic norms of the thematically coherent, personal essay or documentary film. Quoting a conversation with Nicole Wolf from June 2002, founding member Deepa Dhanraj writes about their self-reflexive methods:

“What was very unique and new to see, even in the film practice, was how participatory one could be. How one could maintain participation, not control. How much could we bring them on board at all stages of filmmaking? Though we had the apparatus, the camera, and even the information; we acknowledged where they could influence the process. It was tedious work to show rough cuts and develop the narration iteratively… So there had to be a very respectful relationship and they may have been decisions that led to an aesthetic mess, or proved to be politically a bit difficult. But once we were committed to the participatory process we had to take it to its end.”

Even after the dissolution of the group, such practices remained visible in the later work of a member like Dhanraj. In her film Invoking Justice (2011), the subject is collective solidarity—for Muslim women who want to form their own council of justice, after being denied places in male-dominated Jamaats. The film is concerned with communicating the minutiae of their struggle, especially the contentious discussions that frame their political work. The conflict, therefore, rests not in an imaginary binary between the romantic individual and the realistic collective, but on an aesthetic mode as well, that can reflect the world in a communal register—an actionable world instead of the ironised world or the dream and fantasy world invoked so often by viewers and filmmakers elsewhere. Focusing on its curative properties, Federico Rossin suggests that the world can be shorn of its cinematic trappings by the adoption of alternative cinematic traps:

“So the cure we can take from collectivist cinema can be a coming back to a strong and deep belief in the real, in the world, in the people. Cinema is not just a dream machine: it can be a strong mean to understand, analyze and change reality: the formal researches of these films is an open factory in which we can find old but perfectly functioning tools. We have just to polish them, and to adapt them to our present situation.”

By fusing the collective dimension in production with an interest in representing collectivity in narrative terms, Ektara Collective’s films reinvigorate the legacies of this heritage. Their new film, Ek Jagah Apni, screened at the Kolkata People’s Film Festival, bears a title that reflects the terms of this debate ironically. It suggests that a community is essential even for realising dreams of individual freedom for those who belong to minority communities. This includes the transgender community in Bhopal, two of whom form the central protagonists in this lightly fictionalised feature, as they look for housing in the city. The film leads up deliberately to a climactic sequence where other members of the local trans community and friends of the protagonists, Laila and Roshni, debate the mixed results of their journey across their own city. They try to savour their small victory, suggesting that the meaning of the narrative is also actively produced by its participants. Emending Virginia Woolf’s classic requirement for female creativity to blossom, the need of the hour is to find a room not for oneself but one where excluded communities can discover their individual states of freedom.

Read the first part on the histories of collective film making, Santasil Malik’s review of Nama Filmcollective’s Don’t Worry About India and Ankan Kazi’s piece on archiving collectives.