Images in Transit: Bharat Sikka’s Waiting for Midnight

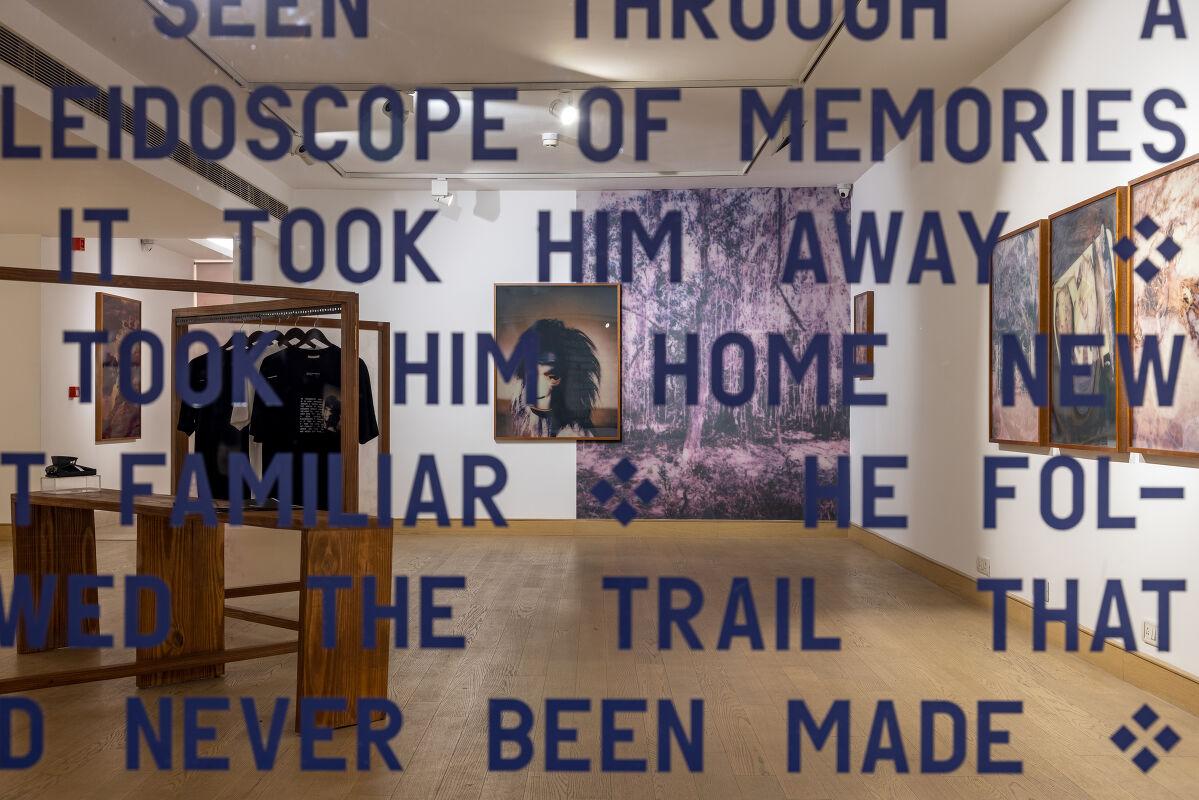

Installation view of Waiting for Midnight at Nature Morte, New Delhi.

In a short reflective piece dedicated to the Spanish painter Miguel Barceló, John Berger enduringly thinks about how a painting manifests or becomes a place. A painter, he writes, stumbles upon a place not in nature or its artistic representations but somewhere in the hollow “frontier between nature and art.” A “slim chance” occurs in the practice and labour of painting when the painter’s body, craft and vision decussate in this liminality. Berger’s oblique yet intuitively perspicuous lines somewhat rang close to Bharat Sikka’s exhibition Waiting for Midnight, which concluded last month at Nature Morte, New Delhi. Collecting quotidian visuals across variegated material renditions, Sikka summons a place tinted with strange familiarity.

Installation view of Waiting for Midnight at Nature Morte, New Delhi.

The work constitutes sixty photographs as an ode to the Goan village of Salvador do Mundo taken over the past fifteen years with a vintage Polaroid SX 70, reportedly the world's first instant SLR camera. In one of his earlier projects, The Road to Salvador Do Mundo (2009), Sikka captured the everyday magnetism of the village and its inhabitants as he moved there after the birth of his daughter. Waiting for Midnight, on the other hand, bears a more spontaneous language, conceived and curated in the last twenty days leading up to New Year's Eve in 2020. From close-ups of a Jenga Christmas tree, a scarf on the clothesline, or an illusory image of a truck inside a glass of water, to figures glimpsed without faces and minimal landscapes of village localities, there is a genial curiosity in the images whose individual references remain mantled in the folds of the photographer’s interiority.

Installation views of Waiting for Midnight at Nature Morte, New Delhi.

Sikka dilates our encounter with these tangible, instantaneous captures as he reiterates and reframes some of them across a range of mediums. The photographer develops the images into large-scale archival digital prints or acrylic prints on t-shirts, one glass partition and a curtain guarding the gallery exit. Through different circuits of representation, the variability of memory and subjectivity manifests in a multi-angulated elicitation of the village. Somewhere between the transits of these multiple image forms and sensations, Sikka mirrors his long-term meandering associations with Salvador do Mundo. The curatorial thrust of the work engenders a place that feeds the individual images and vice versa in poetic reciprocity.

“Untitled” from Where the Flowers Still Grow.

The materialist interrogation of the image has been an invariable occupation in Sikka’s oeuvre, most prominently since Where the Flowers Still Grow (2017), his first photographic monologue that builds an intimate yet undefined account of the people and landscapes in the Kashmir valley. He worked with installations that involved collected objects and often used a scanner to photograph things. Sikka’s conceptual experiments juxtapose different material and image layers to reform our ways of situating narrative components. One recalls Ed Ruscha’s “Ross the Rooster” (1960), where he re-photographed a commonplace image of a rooster by folding and creating multiple creases to foreground the textured interfaces of perceiving images. Sikka’s practice induces a similar perspectival intrigue. In another one of his recent works, The Sapper (2021), redesigning the image form correlates concomitantly with its thematic outline.

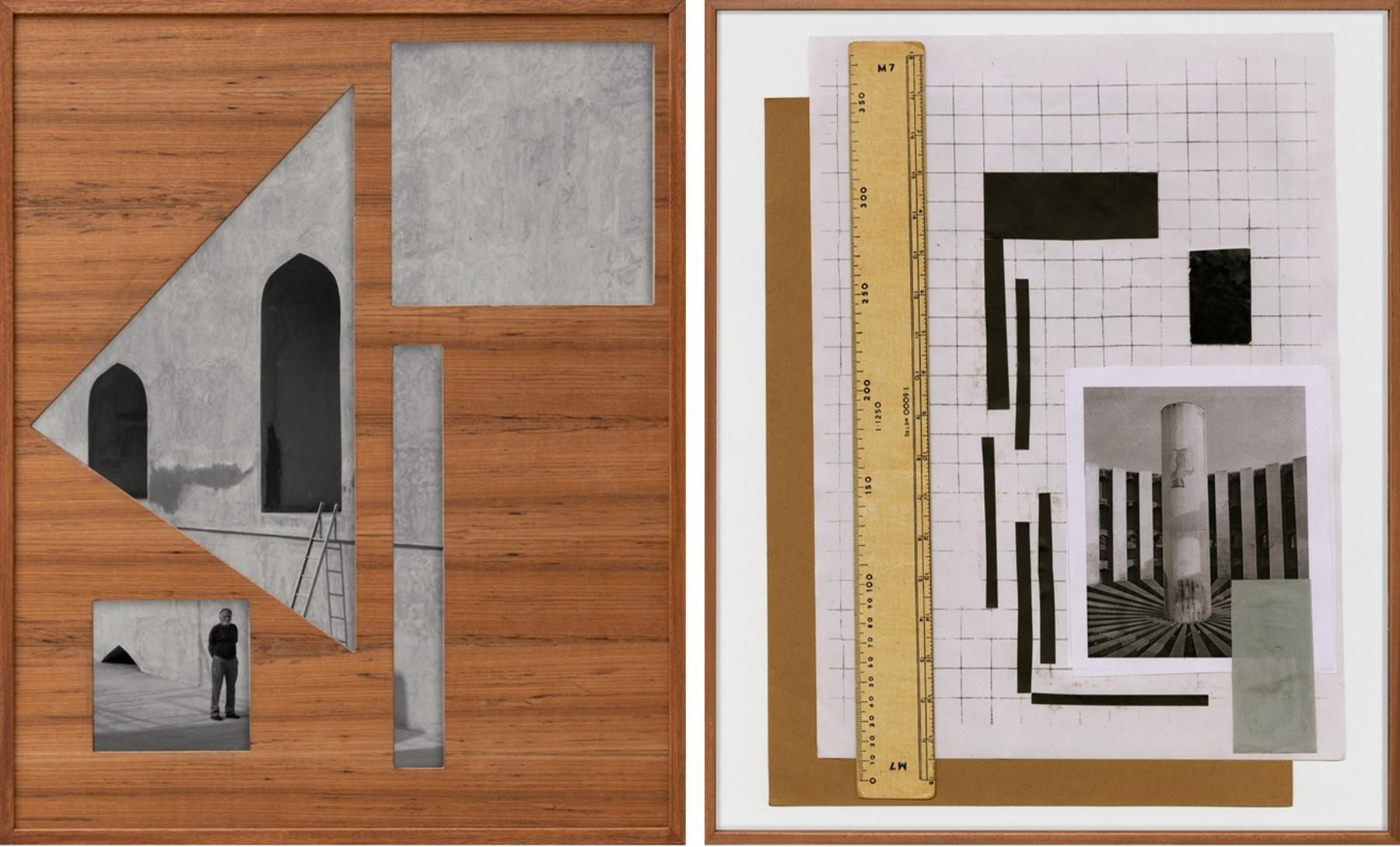

“Untitled” Image from The Sapper.

In The Sapper, Sikka presents a prolonged exploration of his relationship with his father, who worked as a sapper for the Indian Army Corps of Engineers. The artist develops a collaborative method to discern and develop the visual cues of his father’s personhood, preoccupations and professional life. Having witnessed his father play with papers, collages, graphs, blueprints and structural drawings since childhood, Sikka incorporated these material processes into the work. Here, he subjects the image to architectural measures, necessitating the cutting, grafting and reassembling of different elements. In the book’s accompanying text, Charlotte Cotton examines how Sikka enacts his father’s creative mindset to improvise visual strategies, pinpointing “his own parallel actions in the ways that he makes his photographs and photographic objects, orders and assembles.”

“Untitled” from The Sapper.

A steady line of Sikka’s artistic enquiries include questions surrounding masculinity and male identity in India, harking back to his first photography project, Indian Men (2002), which he made while studying at the Parsons School of Design in New York. Reflecting on the solitariness and isolation experienced by Indian men, the work assembles a series of brooding portraits. A similar aesthetic informs The Sapper while occasionally rupturing into slivers of comical absurdity. Running through this and other recent works, his experiments concerning the image form enunciate the processual labour of engineering new visual languages. Thinking alongside John Berger’s ruminations on placemaking, the space between nature and art in Sikka’s photographic works often lies in this labour of continually redesigning and reframing. In Waiting for Midnight, Sikka brings forth places, moods and characters by liberating the image from its material fixity towards new significatory assemblages.

Installation view of Waiting for Midnight at Nature Morte, New Delhi.

To read more about photography in Goa through practices archiving it, revisit Annalisa Mansukhani’s discussions with Lina Vincent and Akshay Mahajan as they speak about their Goa Familia Project.

All images by Bharat Sikka. Images courtesy of the artist and Nature Morte.