Body, Landscape and War: In Conversation with Aziz Hazara

In narratives around war and conflict, each side introduces their own version of the events as they happen, often in real time. Foregrounding the everyday experience of growing up in the middle of war in Afghanistan, interdisciplinary artist Aziz Hazara channels his coming-of-age in such a space. While Hazara experiments with a variety of forms and techniques, a sense of the body and the landscape in conflict remains dominant in his work. Hazara’s acute indulgence in new mediums, the ease with which he brings them together and the subjects he chooses to make a commentary on add to the experience of interacting with his ever-evolving work. Having exhibited across the world, Hazara currently lives and works between Berlin and Kabul. He is also the winner of the sixth edition of the Future Generation Art Prize.

In this edited excerpt from our conversation with the artist, Hazara shares his experiences of living and working in Kabul, the important elements that contribute to his practice and the ways in which the landscape of Afghanistan has changed since the American evacuation in 2021.

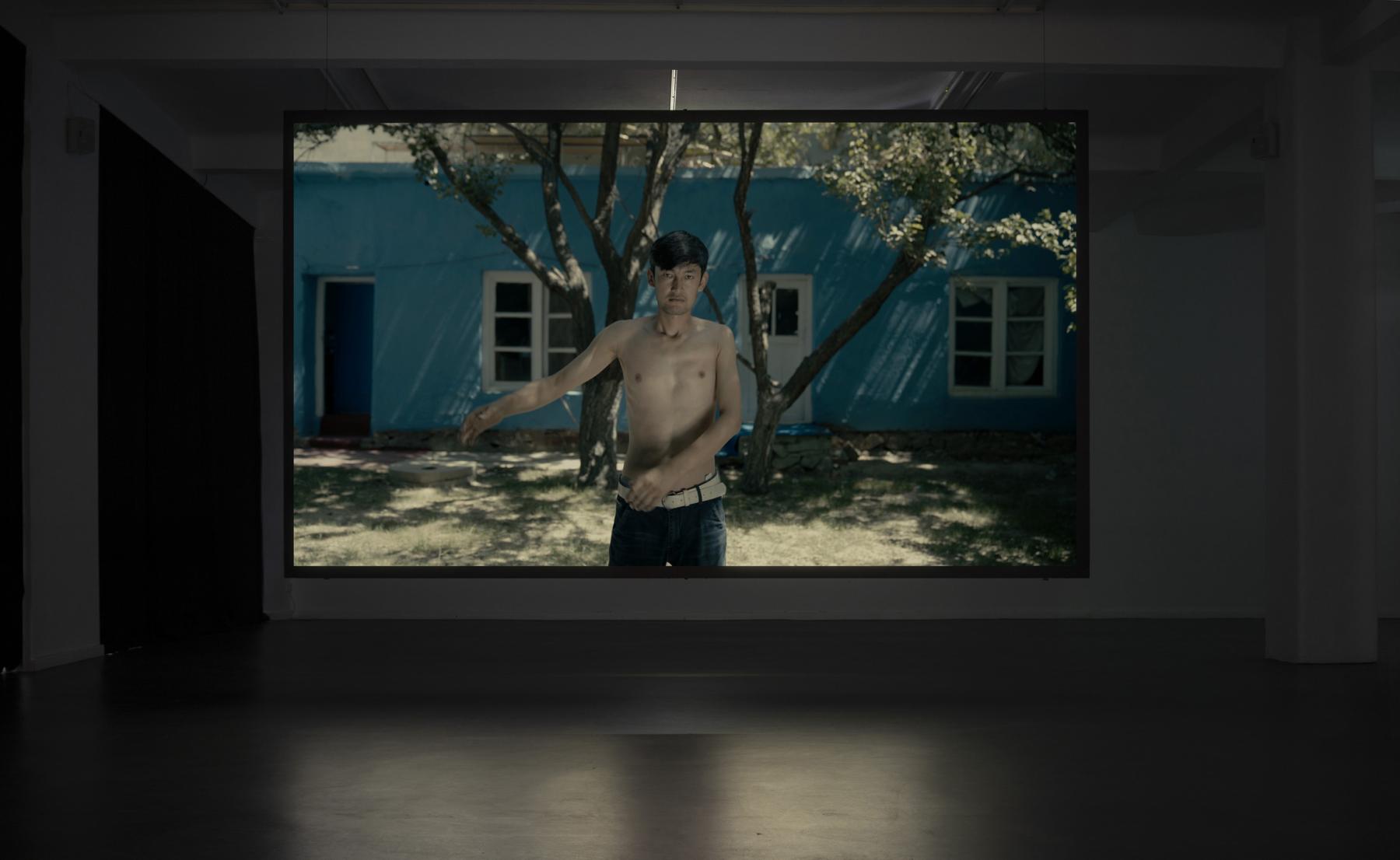

Documenting the body, the landscape and the war in Afghanistan. (Takbir, 2022. Single channel video, colour, surround sound.)

Ankita Ghosh (AG): You currently have several exhibitions running parallel across the world. What has the experience been like for you, to take this story of Afghanistan to so many different parts of the world? Are there any special moments that you witnessed in the audience’s response to your work?

Aziz Hazara (AH): I think the weirdest thing is that at this moment, I am sitting in Berlin while my work travels, but I cannot travel. It is a situation that I do not really know how to describe. But with regard to the works being shown currently, it is mainly because of Covid that most of these are on display right now. Things that were supposed to be shown two years ago got delayed. So yes, it feels good to have all of these reaching different corners of the world, but I wish I could also be a part of it.

AG: Sound forms an important part of your artistic practice. Could you please elaborate on how you began experimenting with sound? What role does it play when you conceptualise a body of work?

AH: When I am conceptualising a work, the vision, for me, is largely sonic and it is only later that the visuals come in. Growing up in Kabul, the sonic experience was very rich and diverse. And then, at some point—maybe by chance or by accident—it just started developing as a part of my practice. I personally feel that sonic experiences stay with me for longer. Whenever I think back to a particular moment in time, it is always the different sounds of a place that stay with me, rather than the exact visual picture of it.

AG: During your time at the Tandem Residency at Colomboscope, you focused on researching the sonic rituals of Jaffna, Sri Lanka. Are there any such traditions from your childhood that contributed to your fascination with sound?

AH: The music of Kabul has developed over time. The city would have resembled something like the streets of Old Delhi in India. From the 1980s until the early 2000s, loudspeakers became very popular in the region. It almost felt like one could not say anything important unless there was a loudspeaker. And then it was everywhere—from the sabziwallah (vegetable seller) to the NGO buses and the mullah (mosque leader) singing. I also grew up at a time when drones and helicopters were introduced into the landscape. When one combines all of this, the sonic experience becomes a cluster of things. Upon listening carefully to these sounds, one is able to identify where each of them is coming from and how far these wavelengths travel. It stays with you for a long time.

Hazara’s experiments with sound mimic the natural landscape where his work is based. (Eyes in the Sky, 2020. Single channel video installation with sound.)

Sound is also strategic. When one looks at the documents of how proxy wars are carried out through loudspeakers, sound forms an important part of the strategy. Be it in Ladakh at the border with China, or in Kabul, or Peshawar. The loudspeakers in Kabul are constantly blaring. Because of the way the city is located geographically, surrounded as it is by mountains, sound also reflects far and wide, creating an element of an echo. This adds to the importance people attach to speakers, because if there is no echo, people would not consider them to be good speakers. People who lack this charismatic echo try to create this effect externally by repeating their words multiple times. All of these little elements feed into the sonic environment of the city.

AG: What is also interesting is the use of text in all of your works on view. How does that take place? And would you say it contributes to your work as a whole?

AH: Often there are incidents or anecdotes that tie into how I think about the titles. For example, I am looking for you like a drone, my love (2021) has an interesting story behind it. It goes back to when the search for Osama Bin Laden was in full swing, and there was a bounty on his head. This was also the first time that drones started to appear in the landscape and were constantly around. And there was a Pashto poem that became quite popular, which went like,

“I am looking for you like a drone, my love;

you have become Osama,

no one knows your whereabouts.”

A lot of poetry that developed around this time made mention of these American drones. Then, in 2021, when the Americans were evacuating, they left behind a massive mountain of trash in Bagram. I thought that it was an interesting juxtaposition when photographing this pile of junk.

Zooming into the expanse. (I am looking for you like a drone, my love, 2021. UV print on paper.)

AG: As an artist, how do you see the negotiation between what we understand as “documentary” and a work that stems from imagination or creativity? Is there a difference between the two?

AH: For me, the lines are very blurred. In a conflict zone, every image that comes out becomes a documentary and it does not matter if it is fictional or real. Most of the time, I work around real time and real events. Fictionalising documents is another strategy, but most of my work happens around particular moments. Sometimes, in my imagination of these events, they take on a new shape that could look like a documentary. But if I look at it another time, it may not. For me, a single event that has an effect on my process becomes, sort of, a documentary.

AG: Takbir (2022) had footage from the American military evacuation. What was the experience on the ground for you while shooting this work?

AH: It was such an interesting time in relation to history. Looking back at it now, one realises that everything was happening so fast. It was so rapid that there was absolutely no sense of time for us at that moment. For example, some of my friends from Kabul, who were waiting to leave, found themselves in Doha six hours later with no idea where they were heading, and then twelve hours later they were in Paris. This moment in time was all about the act of waiting for ordinary people. The airport was only able to accommodate the American evacuation, so people were stuck waiting for extremely long periods of time. There was also Western media propaganda, which created a lot of panic around the event. Everything happened so rapidly that, for us, it felt like everything could change in a few minutes’ time.

Installation view of Takbir from Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, 2022.

AG: Similar to how you revisit the idea of Takbir over a span of a year, do you also find yourself going back to any particular space that you documented over the years? What have you observed with regard to how these spaces have transformed with a change in the power centre of the country?

AH: One of the things about growing up in Kabul was that there were certain green zones within the city. These were fortified areas for diplomats and other foreigners. As an Afghan, one was not allowed into the area unless there was permission from inside. The fortifications were massive and it was a completely different environment there. I had a few friends who lived in the green zone, and I would call to ask them to let me through. Once inside, I would spend hours going around this side of the city and taking in all that was happening because it was not accessible to me otherwise. When the Taliban took over, the whole space completely changed. In terms of the landscape or architecture, Kabul as a city has rapidly changed. I am reminded of this on my visits to its different corners.

For Hazara, sound and light act as metaphors in a land involved in constant conflict. (Takbir, 2022. Single channel digital video, colour, surround sound.)

AG: Finally, but most importantly, I wanted to know if you have been able to showcase your work in Afghanistan.

AH: During the American occupation, there were quite a few opportunities in terms of exhibitions organised within embassy spaces and other such zones. Now, I have no idea if the Taliban would allow for such public viewings or installations. Being from a place where an artist cannot showcase their work when it is about that particular place presents a dilemma. So, I often think of other ways to bypass the current problems. One of the things I figured out early was to make videos, because videos do not need that kind of physical space. They can travel through different mediums and digital transfers. It becomes widely accessible for people who are interested in seeing my work. To this day, accessibility is key to the way I work. For example, for texts in English, I always make sure that they are translated to the local language and then published. I always have video links readily available to share with people who want to see any of these works and reach out. That is my way of making sure my art reaches the land where I come from.

Aziz Hazara’s works are currently part of multiple exhibitions taking place globally. His first solo exhibition in India, No Starting Point for Revolution, is currently ongoing at Experimenter Ballygunge Place. Other exhibitions showcasing Hazara’s works include Condemnation at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), Milan; No Dress Code at PSM, Berlin; and Bow Echo at the Mercer Union in Toronto.

To read more about reflections on Hazara’s work, revisit Sukanya Baskar’s essay on No End in Sight and her conversation with Hazara and curator Muheb Esmat as well as Ankita Ghosh’s review of Hazara’s recent solo exhibition at Experimenter Ballygunge Place.

All works by Azia Hazara. Images courtesy of the artist.