Revisiting Black July: ’83 A Very Short Film

The Black July Riots of 1983, which began in Colombo, are widely acknowledged as the beginning of mass violence in the ethnic conflict that would eventually become the civil war between the Sri Lankan state and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). What began as an act of discrimination against the Tamil community, the Official Languages Act No. 33 of 1956, which legislated Sinhala as the only national language of the country, thus escalated into a series of atrocities that ravaged the entire country in the decades that followed.

While several generations of Sri Lankans experienced the war, the manner in which each did so was vastly different. The education system in Sri Lanka often erases contemporary histories of the country from the curriculum, neglecting events that occurred after independence from the British in 1948. ’83: A Very Short Film (2016), a stop-motion animated film by Sumudu Athukorala, Sumedha Kelegama and Irushi Tennekoon, attempts to capture the historical and emotional nuances of Black July.

The three artists present the fictional story of Anton, a Sinhalese man, whose haunting memories of the riots posit the event in the film. The film suggests that he was one of the perpetrators who caused violence during the riots. In the present day, Anton has a nightmare where he hears the Sinhala word baaldiya (bucket) repeatedly; the word was used widely by the Sri Lankan military forces during the war to differentiate native Tamil speakers (who would pronounce the word as vaaldiya because of their accent) from native Sinhala speakers. In his nightmare, as the word baaldiya is repeated in the background by an unknown voice, Anton walks into his garden. Here, he digs into the soil and finds a bucket of blood that overpowers him in a matter of seconds as he ultimately drowns in this sea of blood. The film then cuts to a scene depicting the chaos of the 1983 riots. Anton’s scream looms in the background as the film ends.

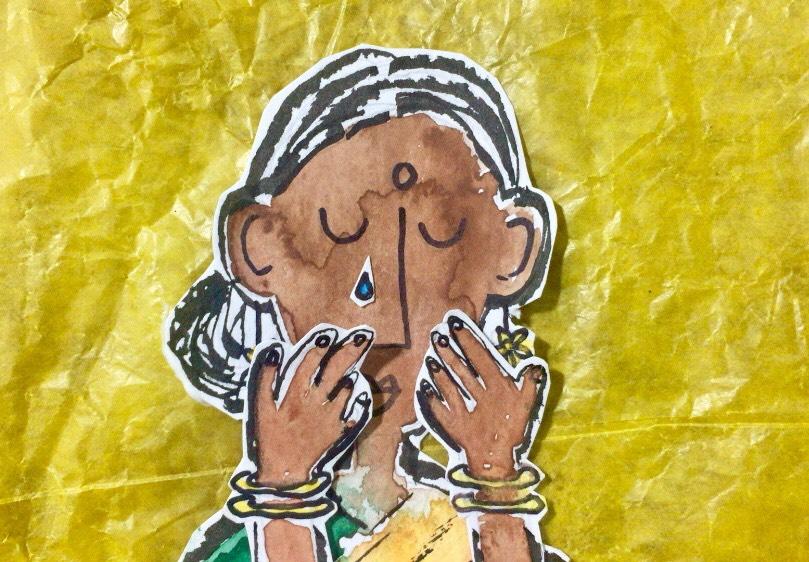

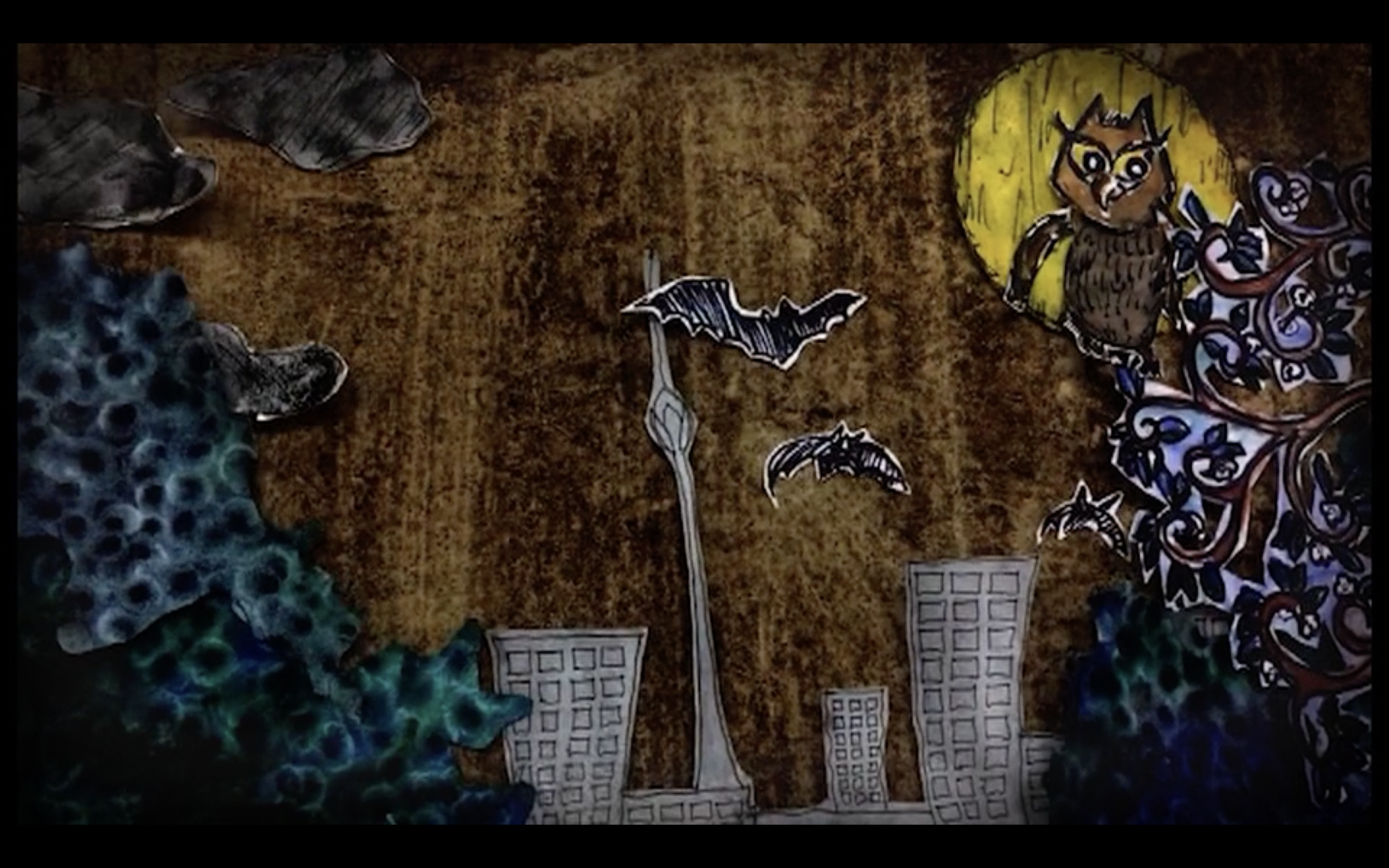

While the film has minimal dialogue, what effectively delivers the story and the emotions are the illustrations and background score. Tennekoon experiments with simple, straightforward silhouettes built of colour, while symbols are carefully positioned in the illustrations. The drawings are detailed and convey volumes about each character, especially Anton. His facial expressions depict impatience, regret, guilt and trauma, as well as the fear he experiences throughout the course of the film. The landscape is rife with imagery of high rises and the Lotus Tower, representing post-war development in Colombo. Anton’s abode in a housing scheme also suggests the fate of many who were displaced due to the war and were then relocated to government housing.

The background score, composed by Chinthaka Prabhath, includes auditory renditions that capture the haunting quality of Anton’s nightmare alongside the collective trauma of the 1983 riots. The film opens with the sound of traditional Sri Lankan drums, signifying a beginning, but the crescendo resonates with the disquiet that mirrors Anton’s perturbations. As the story progresses, the score mainly comprises the sounds of crickets, mimicking Colombo’s nightly atmosphere alongside the deafening silence surrounding the atrocities committed during Black July. A clock ticks in Anton’s room, signalling not just the passage of time but also the delay of his realisation about the role he played in the riots. Finally, the ending scream leaves us with a reminder of the nation’s memories about Black July, as a version of Anton’s memories continues to haunt us.

To read more about forms of resistance and rememberance in Sri Lanka, revist Ankan Kazi’s conversation with Sinthujan Varatharajah on repressed histories of representation, Ketaki Varma’s conversation with Sandev Handy on museum building and Abilaschan Balamuraley in conversation with Liz Fernando on post war migration. To read more about Irushi Tennekoon’s practice, revisit Pramodha Weerasekera’s reflection on the series Animate Her.

All images are from ’83: A Very Short Film (2016), directed by Sumudu Athukorala, Sumedha Kelegama and Irushi Tennekoon. Images courtesy of the artists.