Mourning as Presence: ಮರಣ Marana [Demise] by Vishal Kumaraswamy

Vishal Kumaraswamy is exhibiting photogrammetry and collaboratively generated video works at Église Des Frères Prêcheurs as part of Les Rencontres d’Arles Edition 2023. His work is presented by Party Office and curated as part of the Discovery Award Louis Roederer Foundation show by Tanvi Mishra. Through his multimedia and interdisciplinary works, the artist foregrounds anti-caste thinking across a range of formats in his practice. Recently, Kumaraswamy exhibited his work with the Site Gallery (UK), Movement Radio (Greece), Blindside (Australia), and others, besides being a recent artist resident at the Singapore Art Museum. He is currently a Research Associate at CCA Derry~Londonderry (2022–24), a resident at Onassis AiR in Athens and Grantee with 421 (UAE).

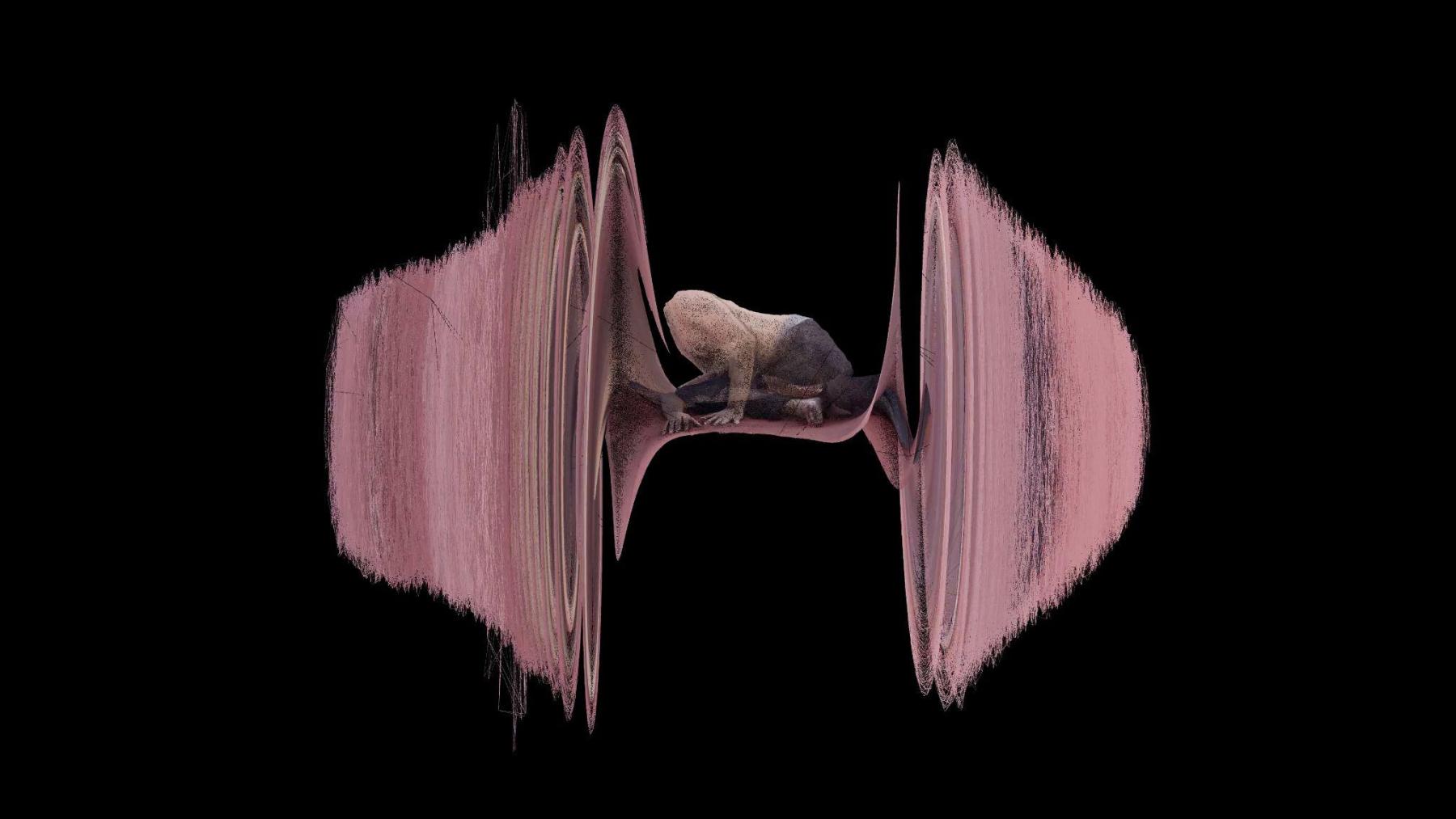

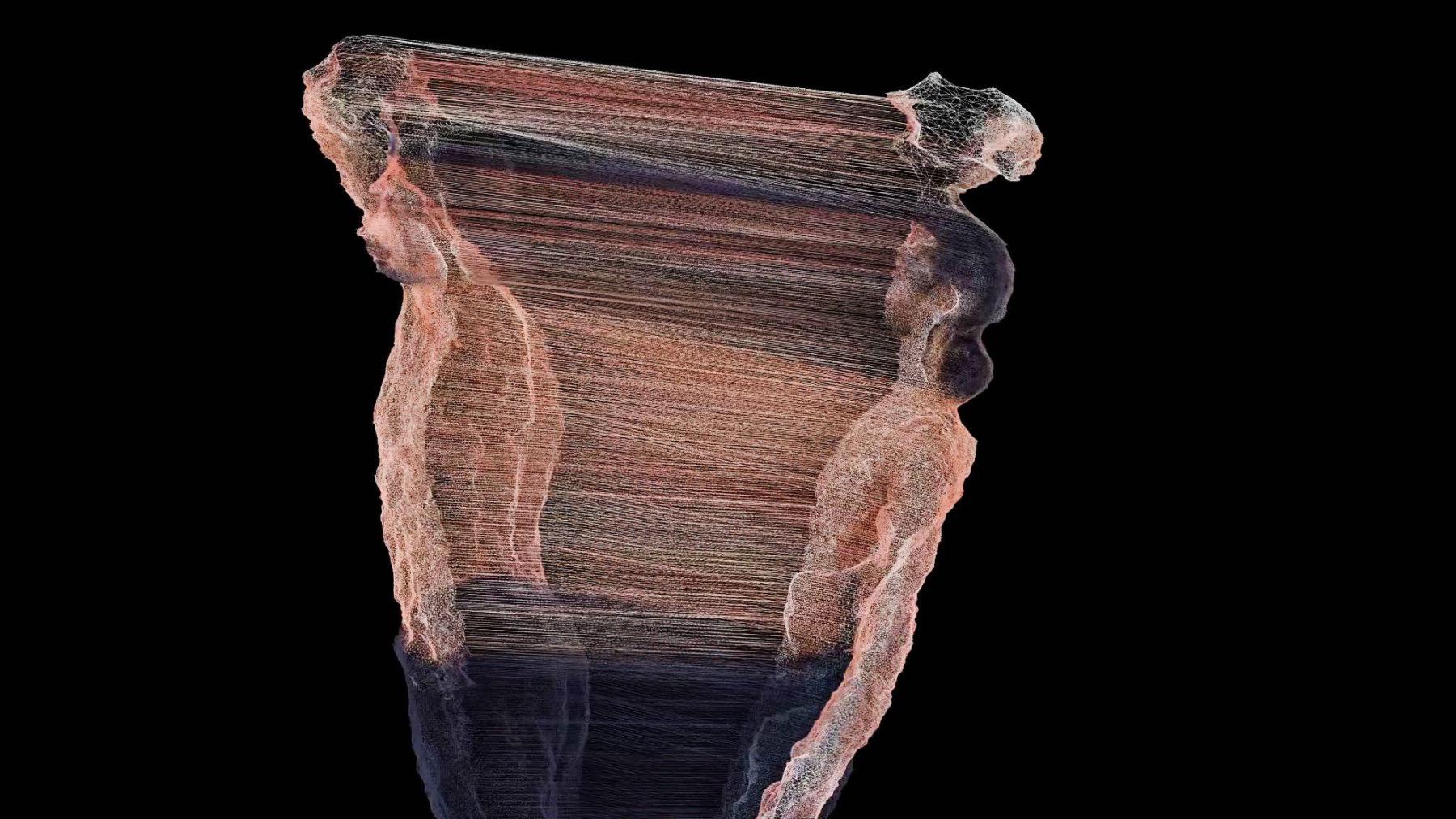

In this edited interview excerpt, the artist discusses his work ಮರಣ Marana [Demise] and the translation of grief following death through mourning as a communal practice. Here, bodily movement and the relay of emotions are conveyed in performative gestures. At the helm of negotiating bodily presence by Dalit communities, these movements foreshadow funerary processions in contested, viciously dominated and hierarchical public spheres. The image—seen in a photogrammetry cast (another relay) and chimaera-like coagulated bodies—enacts the movement of collective mourning towards transformative potentials in digital and physical spaces.

Sukanya Deb (SD): In your video and photogrammetry works, there is a sustained movement that is maintained in the body, individual and collective, perhaps even a set of shifting planes. Could you speak briefly about your articulation of death in ಮರಣ Marana [Demise] (2022–2023)? How do you see the "celebratory" arriving within the practices of mourning in Dalit communities?

Vishal Kumaraswamy (VK): In ಮರಣ Marana [Demise], the movements begin as frozen-in-time renditions of rhythmic movements leading up to a fugue-like state of grief, mourning and celebration within the space of a funeral procession. In this context, the movements come from choreographed re-enactments of bodies within the procession frozen in time to allow for the slow image gathering process of photogrammetry, post-processed with generative programming and re-animated as a continuation of the same movement in digital space. And so, the planes demarcate the boundaries between visible publics and the invisible negotiation of our presence while simultaneously translating these movements from the physical realm into the digital.

SD: It is difficult to ignore the historical and contemporary pretext of Dalit people being denied burial grounds and burning grounds in what can be seen as a breach of the right to grieve with dignity. I also thought of the perverse Upper Caste notion of “contamination” and how specific Dalit caste-based labour prerequisites the removal of corpses. Could you elaborate on the resistant space that you envision and evoke through your works and how the Dalit individual and community intermingle in these movements?

VK: Dalit communities, like mine, bury their dead. The procession that precedes the act is often an assertion of the presence of our bodies within public spaces that are otherwise contentious. Public and private grieving rituals often follow a death in the community. There is an unspoken inhabitation of these spaces, where the status quo of caste-based access to public spaces is temporarily suspended. In this suspended period of time, the procession unfolds both as an expression of mourning and a defiant dismissal of the frivolous rules governing the movement of bodies like ours—both alive and dead. All of this occurs before the procession even reaches the burial grounds. While I understand your point about the context of systemic violence around the many, many atrocities unleashed upon communities like mine, I am preoccupied with the formation of narratives that are richer and broader than these incidents alone. It has been my experience that there is not a lot of space for the same kind of freedom of art-making, artistic rigour and criticality that is afforded to Savarna artists when it comes to the complexity of our lives. In ಮರಣ Marana [Demise], the work takes the event of a death as a starting point, enabling me to shed the weight of that one-dimensional lens through which our bodies, communities and existence are viewed. The work itself moves through the several deaths that the image undergoes and is placed out of reach of the codified Savarna gaze. The resistant space is opened up through the presentation of a vocabulary that is easily accessed by members of the community, while placing conditions of access on the Savarna.

Installation shot of ಮರಣ Marana [Demise] (2022–2023). Image courtesy of Tanvi Mishra.

SD: Could you outline some of the specific movements that were a part of the choreography for the performers and how mourning is inhabited, whether in the body or in public? How do you see collective ritual as a possible emancipatory space?

VK: For me, the movements are akin to heirlooms inherited as tools of joy, celebration, assertion and resistance. The individual movements themselves are an amalgamation of dance, movements of assembly, stillness and movements that are free-flowing in conversation with the rhythmic patterns of the drums. For the specific ones that we froze, we looked at the arc of the body moving across different directions and planes: repetitive back and forth movements, impromptu lateral steps, as well as the full spectrum of the body moving from the sky to the ground, with limbs and extremities pronounced. There are some references to the specific parts of the male subaltern body that are often the site of repeated violence; these are a lot more subdued and coded. The more expansive movements illustrate the widest reach of the body in inhabiting these contested physical spaces and the somatic joy that accompanies unrestricted, non-choreographed flow. The assembly of these images in the context of the exhibition at Arles is the first time that the act of collective ritual moves from documentation into the interpretive space of an exhibition.

Installation shot of ಮರಣ Marana [Demise] (2022–2023). Image courtesy of Tanvi Mishra.

SD: Reflecting on the sonic and cultural aspects of the parai drum as mentioned in the exhibition note, could you comment on the significance of the (imagined) sound in your work?

VK: The work in its current form is part of a larger body of work in which I investigate other digital and media surfaces where individual and collective resistance can be mounted. The parai’s ability to cut through any and all forms of sonic boundaries by ringing in all directions, while crucial to processions in the community, also has other lives. It occupies an integral role within multiple emancipatory movements. In South India, its presence often heralds the start of an event of great importance. As far as the realms that are available to us, the sonic is often the primary mode of engagement in vocalising our arrival, assembly, movements, joy, grievances and currently also our retreat away from these contested public spaces.

Installation shot of ಮರಣ Marana [Demise] (2022–2023). Image courtesy of Tanvi Mishra.

SD: Noting the emergent limbs and chimaera-like forms that resemble a collective form or perhaps a gathering, could you speak to the effect and process of mourning borne in physical gesture and the subsequent breaking and rebuilding of the body?

VK: The collective ritual exists at the time of the actual procession, broken down into individual movements illustrating their different roles. The positions that occur within the procession are reassembled when the entire body of work comes into contact with the gaze of a different audience. I have this preoccupation with shifting the gaze constantly, never allowing it to fix and this is reflected in the extensions programmed into the generative textures as well as the constant refocusing of the subject in the camera movements. The chimaera-like forms, glitches and imperfections of the process illustrate the formation of a collective or gathering, occurring only when the viewer fills in their subjectivities. The gaze must be participatory. The stakes are fully formed only when the viewers can locate themselves in relation to what they are seeing. Whether this is successful or not, a certain kind of grief remains—that of an incomplete image or of incomplete digestion.

To read more about the 2023 edition of Les Rencontres d’Arles, read Annalisa Mansukhani’s two-part interview with Soumya Sankar Bose.

To learn more about image practices around the representation of Dalit experiences, revisit Arushi Vats’ conversation with Diwas Raja Kc as they discuss Dalit: A Quest for Dignity, Ankan Kazi’s reflection on the work done by Dalit Camera and Prabhakar Duwarah’s conversation with Supriya Dongre about examining the oppressive nature of language through her practice.

All images from the series ಮರಣ Marana [Demise], 2022‒2023. Photogrammetry and Direction by Vishal Kumaraswamy. Performance by Parth Bharadwaj and Priyabrat Panigrahi. Photography by Parizad D. Generative image processing by Emilia Trevisani.

All images courtesy of the artist, Riddhi Borua and Manjunath Bonthala, PRNT Gallery unless stated otherwise. Supported by PHOTOSOUTHASIA, INDIA.