Postcolonial Histories of Science: On The Gold of a Yellow Plant

Filmmaker and historian Jahnavi Phalkey’s investigations into the histories of science and technology in India find expression in her films Cyclotron (2020) and The Gold of a Yellow Plant (2021). While the former focused on the life of the eponymous machine housed in the Kuruskhetra University, Chandigarh, The Gold of a Yellow Plant, which Phalkey made with Laurie Sumiye, takes a longer view of postcolonial scientific discourses that were being developed by scientists and thinkers across the decolonising world.

A strain of romantic postcolonial history is kept alive in Phalkey and Sumiye’s short film. Using archival photographs, animation and a haunting soundtrack, the filmmakers present the revolutionary careers of three agronomist-activists—Nikolai Vavilov, Amílcar Cabral and Pandurang Khankhoje—whose work effortlessly upended the political norms of their time.

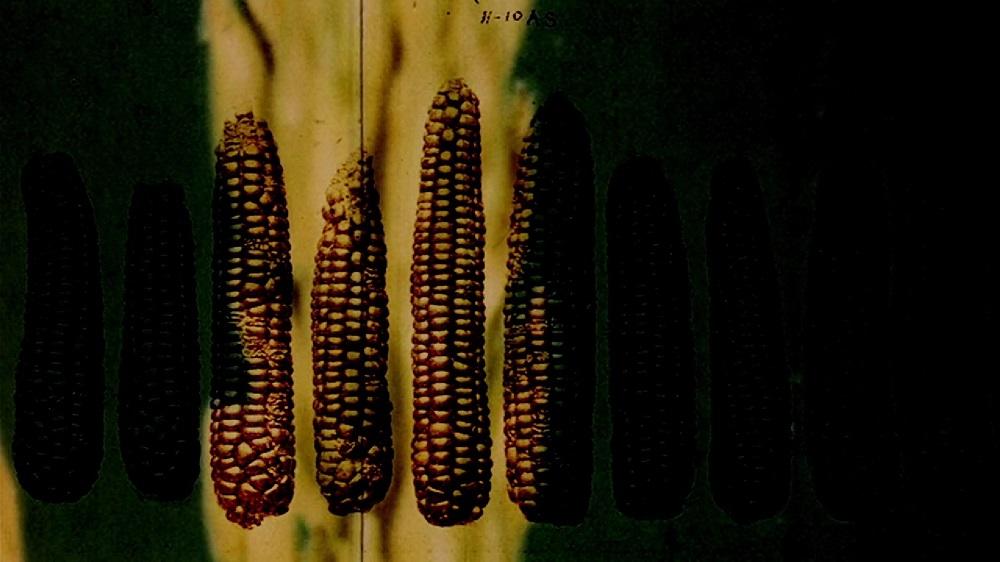

Nikolai Vavilov, who was targeted by a rival scientist and eventually arrested during Stalin’s regime in Soviet Russia, was perhaps the least involved as a dedicated political activist. Yet his work on Soviet-era agriculture, his institution of the famous Leningrad seed bank and his development of potential solutions to reform wheat, maize and cereal crop cultivation to promote greater food security allow him to transcend the strict hierarchy between state-directed scientific research and conscientious humanitarian work under the garb of agricultural engineering.

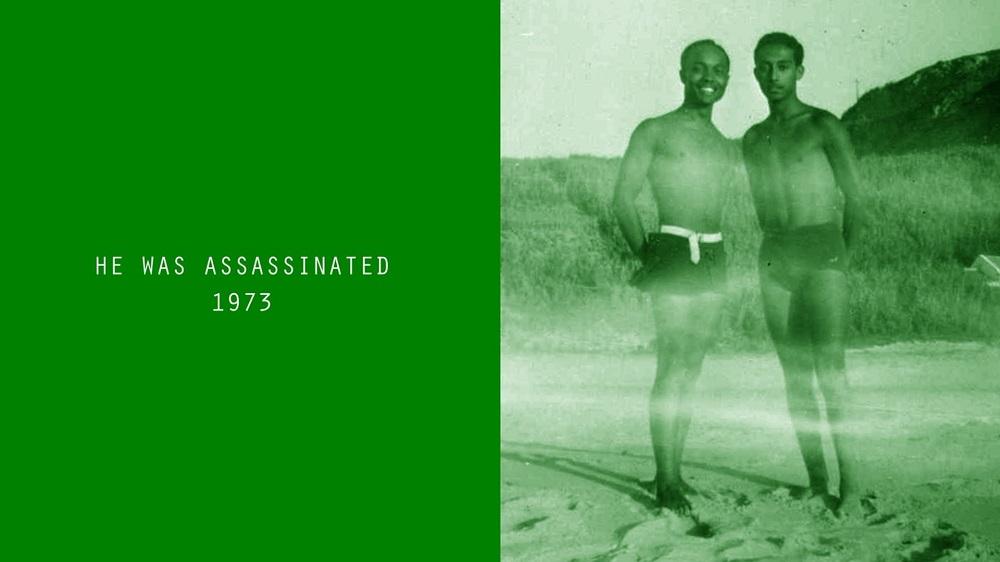

Amílcar Cabral is an icon of anticolonial struggle and a proponent of pan-Africanism. Born in Guinea-Bissau, he led the resistance movement against Portuguese colonisers until his assassination on 20 January 1973, less than a year before his country gained independence. The film focuses on the strong, inseparable link forged between Cabral’s academic interest in soil and seed studies and his political commitment against imperialism. Cabral carried out his early research in Portugal and began organising against their empire at the same time. As some scholars have put it, “Cabral’s understanding of soil and erosion are not dissociable from his project of liberation struggle. His reports on colonial land exploitation and the trade economy, along with his research on soil and erosion, reveal his double agency as a state soil scientist and as a ‘sower’ of African liberation.”

In Cabral’s ecosophical outlook, human ecologies were encouraged to synchronise with natural landscapes in a spirit of political resistance against extractive, capitalist domination. Agronomy became a holistic means towards understanding people’s material living conditions under colonial rule. There was no point in separating the discipline of academic research from the arena of political struggle for the activist-scientist. In his attempt to fuse these discrete domains together, Cabral transformed both, politicising the question of agricultural reform in the context of decolonising societies that were still in the economic thrall of their former imperial powers.

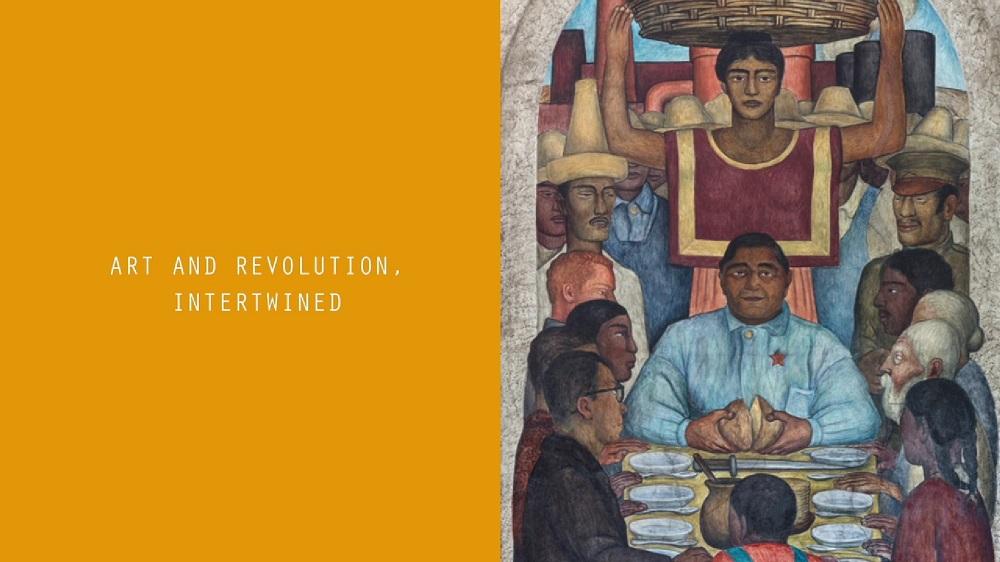

The final figure, Pandurang Khankhoje, was an agricultural engineer whose work informed and clarified the scope of his political struggles against British imperialism. His example offers, in the end, as the film inscribes on an intertitle, “new bread, new hope.” Khankhoje was forced to leave British India as a political dissident. He became one of the founder members of the Ghadar Party, leading a radical, internationalist campaign against British imperialism in India. Having lived through the Indian famine of 1896–97 in his youth, Khankhoje resolved to bring his political commitment and agricultural research in convergence to rally against the larger condition of colonialism. He spent his early student years in Mexico, familiarising himself with Communist revolutionaries. Later in life, when Khankhoje was unable to return to India, he was appointed as a Professor at the National School of Agriculture in Chapingo, Mexico. As his daughter, Savitri Sawhney notes:

“While working with farmers in Mexico, Khankhoje realised their need to learn new techniques and scientific methods to improve the quality and yield of crops. He worked on developing new varieties of high-yielding corn, studying wheat, with particular attention to drought- and disease-resistant and high-yielding varieties. Plant genetics became the subject of his revolutionary endeavours.”

Phalkey and Sumiye’s focus on three radical agronomists from the twentieth-century holds an important lesson. For many scientific innovators, politics was a form of enriching research, informing its blank spaces and committing it to greater universal acceptance. It was not meant to be an object that could be tamed and directed by larger nationalist or corporatist interests in the name of “progress” or scoring civilisational advantages. Instead, as Phalkey and Sumiye’s film shows, the idea of a revolutionary commons was in the making among the decolonial intellectuals of the time, allowing us to glean the solutions for a more equitable future.

In case you missed Ankan Kazi’s reflection on Jahnavi Phalkey’s Cyclotron, read it here.

To learn more about Pandurang Khankhoje’s revolutionary work, revisit Anisha Baid’s two-part conversation with Savitri Sawhney.

All images from The Gold of a Yellow Plant (2021) by Jahnavi Phalkey and Laurie Sumiye. Images courtesy of the directors.