Running Away and Hiding: B.V. Karanth at the Movies

B.V. Karanth’s legacy can be read in a pretty straightforward manner: upon graduating from the National School of Drama (NSD), New Delhi, he set up a roving theatre group named Benaka and dabbled in the emerging parallel cinema movement. He went on to translate Girish Karnad’s play Tughlaq (1964) into Urdu, despite a tenuous grasp of the language—Karanth’s expertise lay in Hindi and the various languages of the Dakshina Kannada region, be it Tulu, Konkani, or Kannada. He later became the director of his alma mater, taking students to the countryside to acquire various folk traditions by osmosis. Following an infamous stint at Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal that led to a media scandal, he finally retreated back to Karnataka to set up Rangayana, a repertory in Mysore, where he lived a pretty discreet life until his demise in 2002.

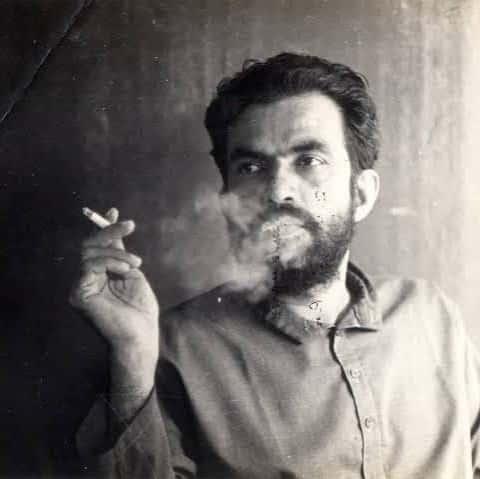

B.V. Karanth.

It is for this reason that Arul Mani’s tribute to Karanth is intriguing, as it focuses more on his relatively brief foray into cinema. Mani highlights Karanth’s seemingly ubiquitous but discreet presence in his life:

“B.V. Karanth was there in every one of the Kannada films I remember discovering via Doordarshan. His music transforms Ghatashraddha via its understated commentary. In M.S. Sathyu’s Kanneshwara Rama, a folk ballad accompanies the sombre procession trailing a captured bandit and the memories it compresses stand in ironic relationship with the tone in which the film unfolds. And in Prema Karanth’s Phaniyamma, it is his themes that amplify our sense of the slowness that is imposed upon a child-widow. When he directed, he seemed always to co-direct. Films like Vamsa Vriksha and Tabbaliyu Neenade Magane seem thus to owe their existence to Karanth’s capacity to step aside for Karnad to do one kind of lifting while he focused on investing layers and textures into the project. Chomana Dudi, where Kasaravalli stepped in as associate director, is this capacity at its peak.”

1.jpg)

Chomana Dudi (1975).

In the documentary B.V. Karanth: Baba (2012), directed by Ramachandra P.N., Girish Karnad presents candid and often rambling reminiscences of his former collaborator. Here, Karnad ruthlessly downplays Karanth’s career after the Bharat Bhavan scandal and attributes his inept handling of the police interrogation in the Vibha Mishra case to a primordial fear of the police after an instance of petty larceny in his truant youth. The incident supposedly caused Karanth to flee his native village, Manchi, in the Bantwal region of Dakshina Kannada and find his way to Gubbi Veeranna’s itinerant drama troupe.

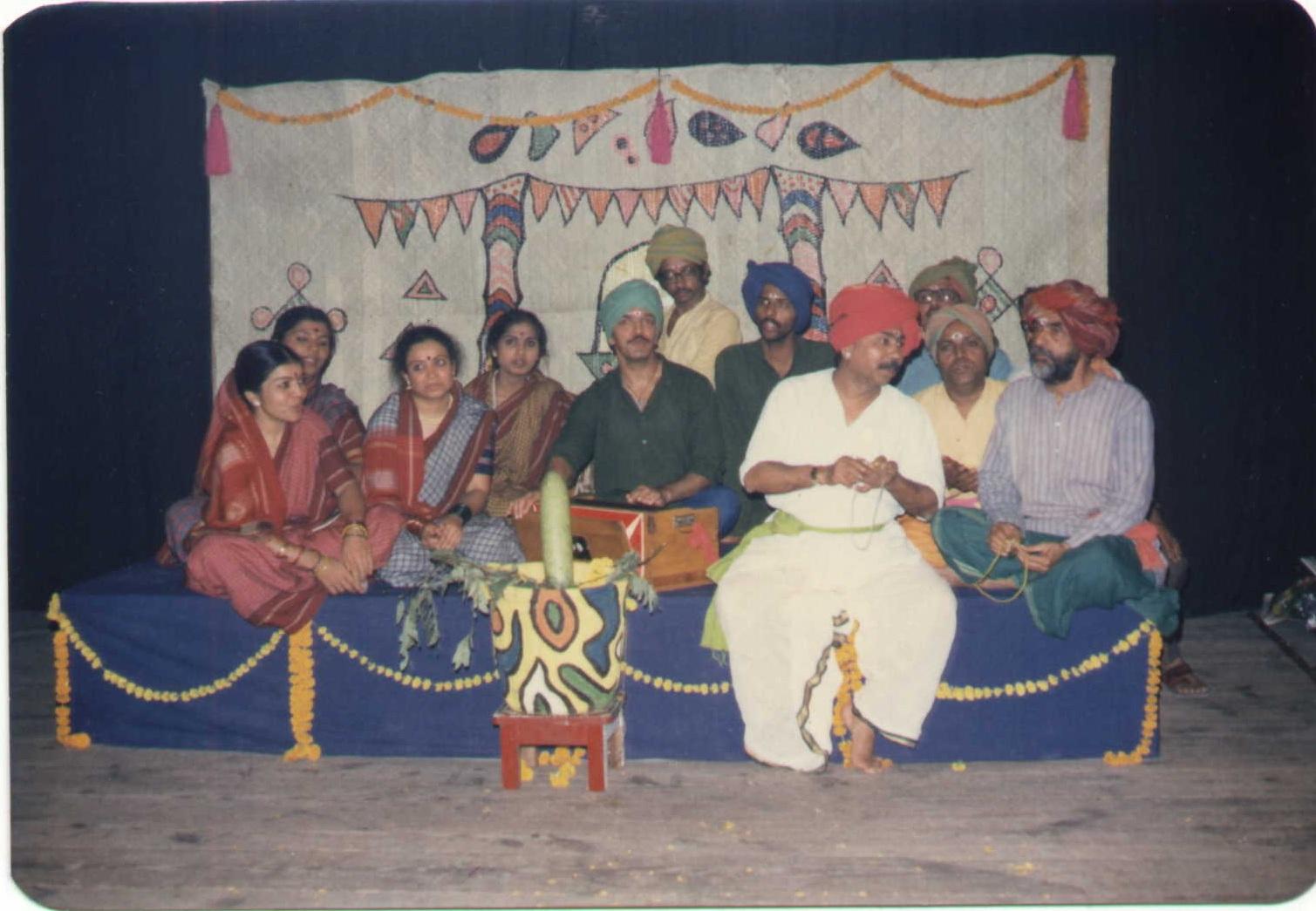

B.V Karanth (far right) during a tour of Jokumaraswamy.

It was on these seemingly terminal yatras that Karanth developed an eye for how people across the country carried themselves and an ethnographic ear for their dialects and music, so essential to imbuing the films he worked on with the aforementioned “layers and textures.” Karnad himself acknowledges the distinct social milieus that led to their rich collaborations, which earned them the sobqriuet “Ka-Ka Jodi”. While both were Brahmin men, Karnad found himself on the more aristocratic side of the caste makeup, with an Oxford education and a studious familiarity with the classics of the Western canon. Karanth emerged from the more pauranic mode, his travels and command over various languages positioning him as a vernacular cosmopolitan.

Karanth (in the middle) with his theatre group.

Perhaps Karanth’s most interesting and criminally neglected cinematic offering was the children’s film, Chor Chor Chupja (1975). Here we see Karanth throwing down the gauntlet against the traditional dictum of the complications of directing children and animals to produce a film that both acknowledges the intelligence and capacity for wonder in its audience. A simple tale of an unlikely friendship between a monkey and a mute boy, starring a wiry, young Om Puri, the film brings to the fore Karanth’s greatest talents, staging the most subtle gestures, his trained ear to the colour that language provides and music. As Mani notes, Karanth did not shy away from crediting the dog that appeared for cameos in Chomana Dudi (1975) and Chor Chor Chupja. Karanth is at ease taking wide shots of a monkey that is rather content not doing any tricks for the camera. For these reasons, a more serious academic inquiry into his films must commence.

To read more about histories of Kannada film, revisit Satyavrat KK’s critical reflections on Shankar Nag, the decline of Bengaluru’s Kannada film industry and the representation of the public sector in cinema.