Postcolonial Gestures: Cultural Transference in Creature

Akram Khan’s Creature is a psychological thriller that captures the fusing of classical European ballet with the formal movements of Kathak, the classical dance form from Northern India. The long hem of the dancer’s military frock coat in a ballet pirouette seamlessly transmogrifies into the whirling tanoura skirt of Sufi dancers or even resembles the cascading long skirts worn by Kathak dancers from the Jaipur or Lucknow gharanas (school of dance) immersed in their laykari (rhythm and timing).

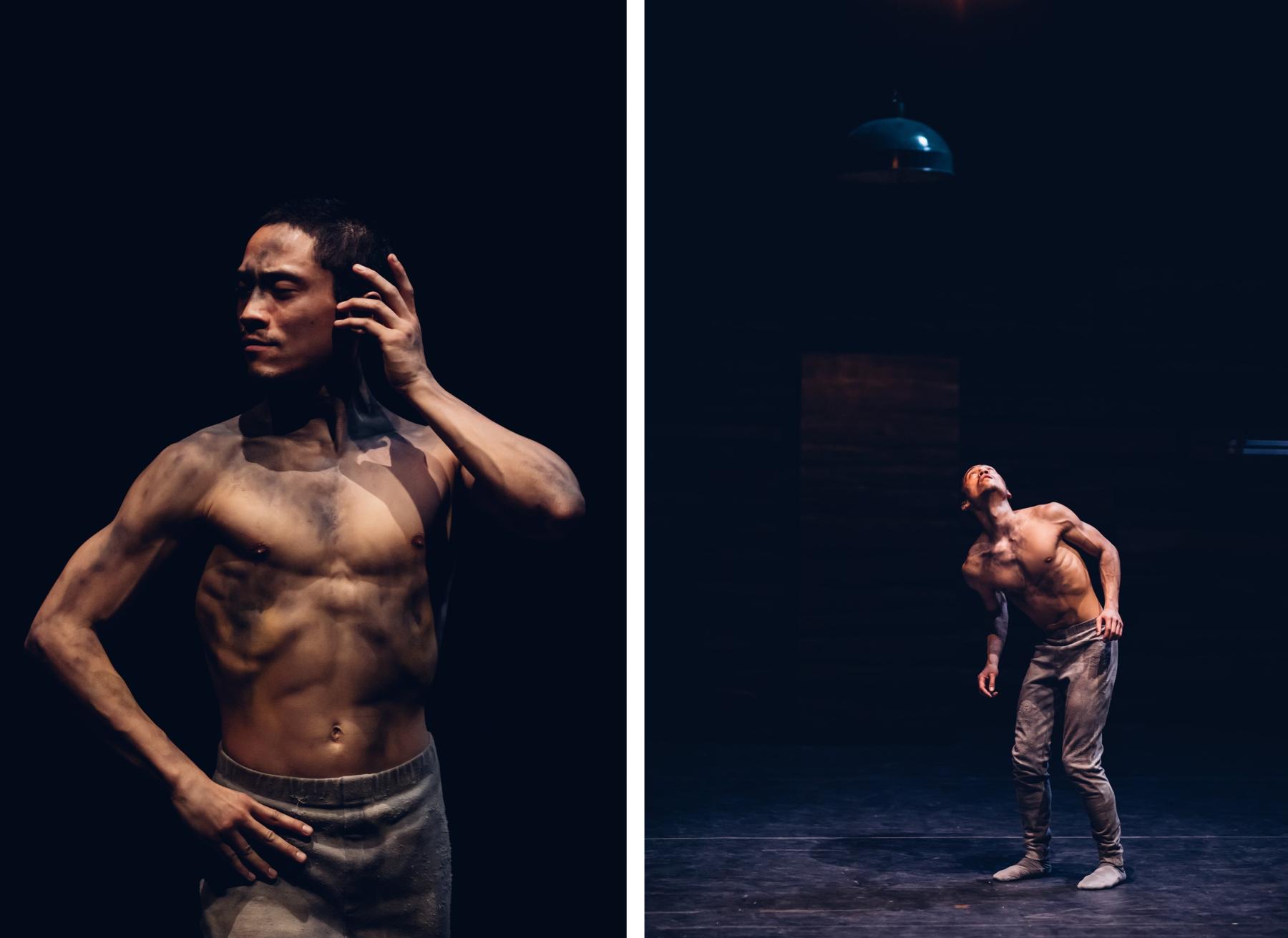

Stills from Creature (2022) by Asif Kapadia. Images courtesy of BFI productions and the Akram Khan Dance Company for the English National Ballet.

Kathak is among the eight classical dance forms of India, and its aesthetics evolved under the patronage of the royal Mughal courts, whereas the remaining classical dance forms of India originate from temple dances practised by the devadasis, who were sacred prostitutes for upper caste men. The sacral figure of the devadasi (temple dancer), as the subaltern, is often highlighted in the sexual economies of pre-capitalist feudalism in India. This context is replete with the problematic sanctioning of temple prostitution in collusion with religious morality and the social hierarchies instantiated through the caste system. It resulted not only in the economic exploitation of the subaltern women but also in their spiritual domination. The predicament of temple prostitutes has been famously depicted in Vijay Anand's film The Guide (1965), based on a novel by RK Narayan. It stars Dev Anand as a young tour guide who falls in love with Waheeda Rehman, the daughter of a devadasi who has been asked to stop dancing after attaining a respectable social status by marriage to a wealthy archaeologist. To this effect, it was only through the legislative action of the Madras Devadasi Act (1946) that devadasis achieved autonomy as political citizens, and the practice of dedicating young girls to temple prostitution was abolished.

Waheeda Rehman and Dev Anand in The Guide (Vijay Anand, The Guide, 1965).

Kathak originates from the Sanskrit word “Katha” meaning stories. The narratives often allude to tales from the repertoire of Hindu mythology. However, as an art form that flourished under the patronage of Mughal kings and for a courtly audience, the spiritual aspects of these stories were circumvented by an added emphasis on highly stylised choreography that focused on aesthetics and techniques. For instance, the Tatkar, known as the fundamental footwork for Kathak, is a grounding force set to a rhythmic pattern and accompanied by the rainfall of ghungroos (anklet bells). This signals towards the prior Indo-Persian fusion of dance forms, previously attained in the gestures and movements of Spanish Flamenco with a similar use of castanets (clackers).

Waheeda Rehman performs the snake dance (Vijay Anand, The Guide, 1965).

In Akram Khan's Creature, we find a hybrid meeting point for cultural transferences, where the gestural composite of South Asian classical dance form melds with the grammar of classical European ballet. This form exhorts us to think about colonial and racial hierarchies that are operative in dominant representations of modern dance. And further, how these inequities are non-verbally reproduced through the dancers’ bodily gestures and comportments while remaining outside language. Khan’s oeuvre and his existing repertoire of gestures pose relevant questions about the search for one’s roots by interrogating the histories and legacies of colonialism. The text can be read as an exploration of the abuse of power and authority vested in classical art forms as cultural heritage, thereby placing them above and beyond criticism, or through the racialised insinuations pulsing through popular stories about a feral boy from the colonies in this modern adaptation of the canonical literary text by Rudyard Kipling, The Jungle Book.

The intersection of colonialism and the gestural repertoire of classical Kathak in Indian cinema has been depicted in the 1977 film Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players) by Satyajit Ray. In one sequence, the Nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah (Amjad Khan), who is a poet and connoisseur of Hindustani classical art, watches a Kathak performance by a courtesan immediately after receiving news that he has been abdicated from his throne. His close friend, General Outram (Richard Attenborough) of the British East India Company, has robbed his kingdom and dishonoured a longstanding treaty of friendship between the Nawab and the Company.

Saswati Sen performs a Kathak sequence at the court of Wajid Ali Shah (Satyajit Ray, Shatranj Ke Khilari [The Chess Players], 1977).

For this sequence, Ray recruited the veteran Kathak dancer Saswati Sen to perform “Kanha Mein Tose Haari”, which was choreographed by the late Pandit Birju Maharaj. The choreography depicts Radha's modesty being outraged playfully and flirtatiously by Krishna. At court, the stylised performance of Radha's dishonour serves as a veiled metaphor for the Nawab's own colonial subjugation. As Sen gracefully enacts the indignation at the overtures of sexual courtship, the implicit meaning is tainted by Wajid Ali Shah's own shame and colonial subservience. The Nawab is left with no option but to accept General Outram’s betrayal and the resulting occupation of his kingdom by the Empire.

The classical gestures (abhinaya) of love, beauty and honour in the Kathak tradition staged at the court of the Muslim Nawab, albeit with the aid of lyrics, collaterally communicate different registers of meaning. On one hand, the cultural transferences depicting the sexual economy of love fuse Hindu mythology with Islamic aesthetics. On the other hand, it also transmutes the operations of colonial greed, which has no qualms about dishonouring treaties or violating human subjects for the sake of material acquisitions, as one has historically witnessed in the making of the British Empire. Revenants from the Kathak performance in The Chess Players may as well haunt the latest collaboration between Asif Kapadia and the Akram Khan Dance Company.

The East India Company and the King of Oudh (Satyajit Ray, Shatranj Ke Khilari [The Chess Players], 1977).

Asif Kapadia’s cinematic capture of the gestures and choreographies of movements in Creature explores the terrain of fusing Indian classical forms with Western ballet. Creature succeeds precisely because it is able to highlight the racial and colonial hierarchies of cultural transferences that are precursory to language. It leaves us to reflect on how one cannot begin to examine the attribution of value to cultural art forms without adequately interrogating the material histories of colonial extraction. This includes the systemic institutional desecration and hoarding of postcolonial cultural artefacts as fetish objects in the basements of museums located in North America and Western Europe.

Saswati Sen performs a Kathak sequence at the court of Wajid Ali Shah (Satyajit Ray, Shatranj Ke Khilari [The Chess Players], 1977).

In case you missed the first part of this essay, you can read it here.

To read more about artists that question the representation of the colonial body, revisit Najrin Islam’s conversation with Renluka Maharaj’s on her practice of reclaiming women’s agency in the archive.