Madness and Mandates: Pramod Pati's Film Experiments

A multi-layered audio-visual mix of rhythmic and cacophonic sounds and breathlessly paced visuals, Pramod Pati’s film Explorer (1968) offers a crucial entry point into experimentation with film form at the Films Division of India (FD) with its complete non-conformity to the prevalent style of filmmaking. Explorer was made as India’s entry to the “mission of youth” experimental film festival in Mexico City and was sponsored by the organising committee for the games of the XIX Olympiad 1968. In spite of this mandate, filmmaker Mrinal Sen interestingly interpreted the film as a depiction of intense love for the medium, as an exercise, and a highly stimulating experience—what he called the filmmaker’s “desperate bid to break all tried conventions and create new ones.” Sen claimed that it was good that FD, unlike commercial cinema, was venturing into this less explored “madness” through people like Pati, as they were “undoubtedly breaking new ground.”

Born in 1932, Pati was a graduate of science and a cinematography diploma holder who became renowned for his experimental animation in films. He studied puppet animation at the Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts (FAMU) in Prague under Jiří Brdečka, Jiří Trnka and Eduard Hofman. By the mid-1960s, Pati would join a constellation of filmmakers like S. Sukhdev and S.N.S. Sastry who, under the dynamic supervision of Jehangir Bhownagary (Chief Advisor [Films] to the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting of India from 1965–67), experimented with their artistic styles as FD’s film practice underwent substantial changes. Pati’s films are indeed marked by both a change in content and a radical use of form at FD. His other short films like Perspectives (1966), Claxplosion (1968), Six Five Four Three Two (1968), Trip (1970) and Abid (1972) were all part of the “Experimental” category of films at FD as well. A closer look at some of these films allows us to see that this “madness” of experimentation associated with Pati’s formal engagement is closely linked to the experimental spirit of working creatively with government mandates.

This spirit is on display in Explorer, as it employs an anti-narrative form along with disruptive and flashy imagery to capture the dichotomies of youth culture in India in the 1960s. Not only is there no narration, the soundtrack is as elusive as the visuals in the film. It never “compliments” the visuals, but rather is almost dissonant with them. The film mobilises the use of analogue techniques, like shift-focus and solarisation of the images, to enhance the incoherence of the mass frenzy. True to its evocative title, Explorer captures this frenzy through the mind of an explorer as they engage with their immediate surroundings. With an effervescent psychedelic energy, the camera is constantly searching and registering what it sees, even as everything always seems to be out of grasp. We witness the phantasmic apparitions of the explorer’s mind as objects are rendered unrecognisable or transformed into something else with endlessly rapid montage or shifting focal planes. The film is a statement on the maddening intensity of the changing times, which the filmmaker scours through only to find an ever-intensifying circular journey.

We are introduced to the title of the film through an effect that resembles the tuning of a television to adjust the audio-visual signal to sound and picture. This is coupled with the high-pitched, irregular sounds of electronic machinery and the rhythmic percussion of a Damaru (two-headed drum). It seems like we are seeing a distorted projection of the film’s title on shifting blinds on a window. The text alternates between two different typefaces and plays hide-and-seek with us. Immediately after the jarring opening title scene, which barely lasts two minutes, we hear an infant crying over a visual of a religious idol. The camera then racks focus to a burning lamp, and then to a person chanting something inaudible but what seems like a ritualistic chant. With a dramatic cymbal sound, percussive beats launch a rapid montage of hypnotic visuals of people dancing in a trance. We see split second shots of euphoric youth head banging to the beats, sometimes framed against the light. The camera’s movement matches their rhythmic thumping, thereby making the cuts invisible. The disjointed beats irregularly shift pace, sometimes slowing down or changing rhythm.

.png)

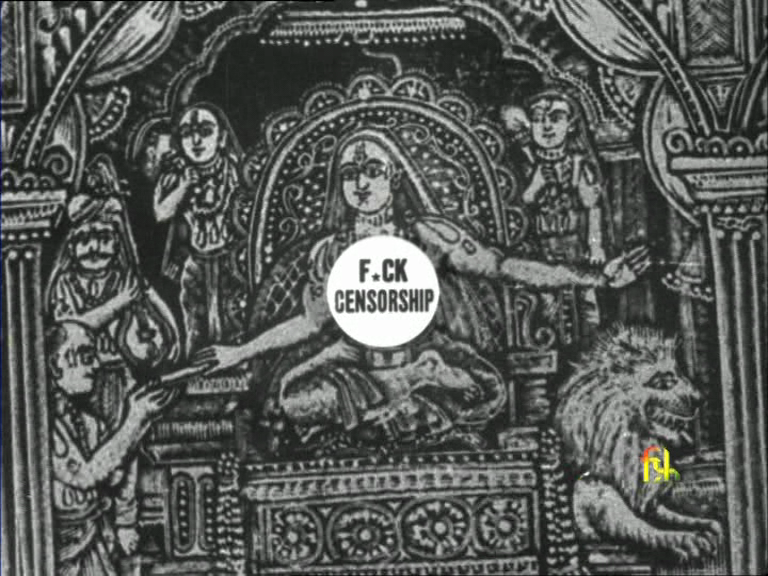

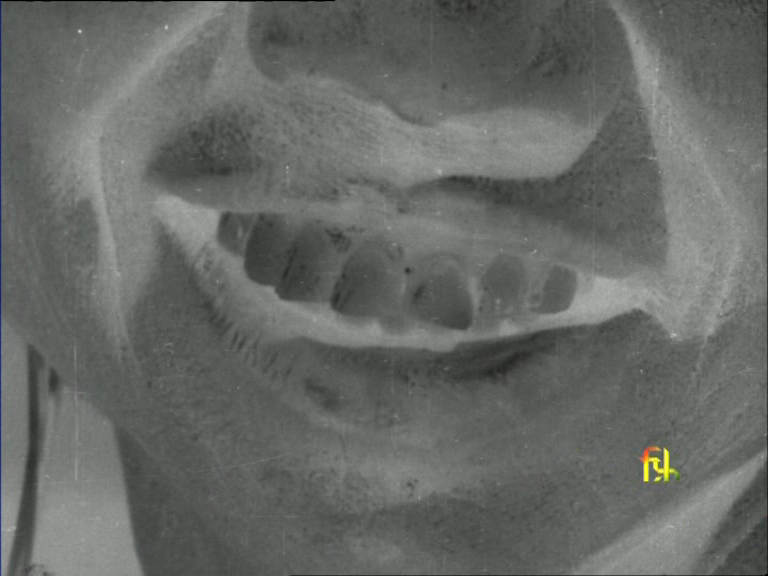

In between these frantic and almost incomprehensible shots, we see a long shot of the big room in which people are dancing. The symbol "Om" looms large as it hangs from the ceiling over the feverish mass of people. The monochromatic images of people are solarised, a technique that reverses the image’s dark areas to white and vice versa. It renders people’s faces unrecognisable and turns them into mere splotches on celluloid, while the iconography remains larger than life. The camera repeatedly pans among the dancers at a breathtaking pace, so they almost seem like a blur, and then systematically cuts to a still image of religious idols. This pan-image-pan editing style is also interspersed with images like a hand showing astrological markers painted upon it and religious icons like the Hindu Lord Shiva with his weapon. One of the most significant images is that of a feminine figure (perhaps a goddess or a queen), marked right in the centre with text that says “F*ck censorship” in a direct indictment against censorship practices at film institutions.

After this sequence, which highlights the dominance of pop-Hindu iconography in the 1960s—directly signifying the counterculture movement and hippie culture of the era—we see a montage that can be described as the impressions in the mind of a meditating man. Pati juggles in between images of modernity like laboratories and computers vis-à-vis religious iconography, implying a curious confluence in pop culture and the youth culture of the time. We see visuals of ritualistic chanting by Hindu pundits colliding with drawings, shapes and objects. On a soundtrack of classical music, we see a destabilising image where the camera constantly changes focus while framing an organic structure like a dense tree with bare branches that appears utterly elusive to comprehension.

.png)

All this while, the soundtrack straddles between repetitive sounds and musical sounds that act as interludes. The only words that appear coherent are “Ramayan, Parayan” and “Puran, Kuran,” which are slowly pronounced and then repeated in a female voice. The film maintains its jarring pace throughout, pausing only at certain multiple shift-focus shots, especially in labs where laboratory technicians seem to be working on different things. The focus shifts from one glass tube to another, finally revealing the person working on, for example, a microscope. As Pati uses the techniques of continuously shifting focus, solarisation, or blurry and incomprehensible visuals, he shifts the optical register of the image to the experiential. Thus, we experience the interiority of the explorer through images and sounds that are destabilising as they reject any finality of meaning. The layered images—with constantly changing focus or the solarised film strip—resemble properties of an X-ray film image. They offer a simultaneous view of the inside and outside, and illustrate a phenomenological use of filmic materiality and form. Not only is the form completely unyielding towards conformity, but the content of the film edges towards a rebellious tendency. The film is not a glorifying edifice of the urban youth of the time; it is in fact an elegy, signifying a hysteric dissonance that dominates the period.

To know more about experiments with film and their histories, read Ankan Kazi’s essay on Bangladeshi short films as alternative cinema and Silpa Mukherjee’s examination of the Emergency and its effects on the star-system in India. Also, listen to a conversation by Debashree Mukherjee, on her book examining colonial filmmaking and ecologies of cinematic practice.

All image stills from Explorer (1968) by Pramod Pati. Images courtesy of the author and Films Division.