Pramod Pati’s Film Experiments: Negotiating Film Form within Governmental Frameworks

In the first part of this essay, we looked at Pramod Pati’s Explorer (1968), which was produced by the Films Division of India (FD). The subjects of the film seem like they are madly in search of something, and this is echoed in the camera’s relentless movement and refusal to stay at any one image. The film visualises the innermost recesses of the mind of the youth of the 1960s as they search for meaning. Yet its circular structure highlights how this is always out of reach. In its style and structure, the film invents a form that mirrors the frenzy of the youth, where the filmmaker refuses to capture a stable image, and instead, shaky, dizzying, hypnotic and trance-like sequences follow.

Still from Explorer (1968)

Another film by Pati that follows the same course of exposing the interiority of the artist’s mind is Abid (1972). Based on the painter Abid Surti, who once expressed his desire to “live within a painting”, Pati decided to make a film on him with the same idea. The film was made in collaboration with various animation artists and featured music by Vijay Raghav Rao. Abid employs the pixilation technique, where a moving object is shot frame by frame and then made to appear as if in motion through editing. The result is a new kind of movement that appears lively, agile and erratic. Following the psychedelic style of Pati’s other work, the film shows the artist emerging from a hole in the ground and continuously transforming the white room with painted images on the walls, ceiling and floor—as if creating a live painting. With an eclectic soundtrack and the surface of the room undergoing continuous change, the film exteriorises the interior life of the artist’s mind with a style that blends pop art aesthetics with trance film.

Still from Abid (1972)

Like Abid, which used pixilation to create an unreal temporality and movement within a single frame, Trip (1970) also experiments with movement and the passage of time within the same frame. The film can be seen as a city symphony film, where places in the city of Mumbai are shot through time-lapse photography. These shots are then sped up to show the entire happenings in that space in a matter of a few seconds. Along with the visuals, the audio is tweaked too, as city sounds are made to appear strange with the qualities of a rhythmic drone. Thus, unlike city symphonies, it does not employ a melodic use of sound and is not interested in the microcosmic details of city life.

Still from Trip (1970)

Trip shows the following spaces in Mumbai: a train track, a wide street in Mumbai with parking, the dhobi ghat, a beach, a street in South Mumbai, Racecourse and the Gateway of India. In every space, time from dawn to dusk is captured. The resulting images are shown at a highly accelerated speed, so much so that they seem completely animated. The frame is always fixed at a long shot of the place and then, through time-lapse, the activity in the place unfolds. While the monuments, buildings and beaches remain static, the movement of people continuously changes the image. We see shadows move across the frame as the direction of the sun changes over the course of the day. As the same frame gets layered with the movement of people, objects, shadows and light, the surface of the image transforms. Curiously, every sequence has interludes of illustrations of the sun. Thus, the elusive city is seen on the surface of these frames, marked by the changes in time, i.e., the changes in the day and night cycle. The frames are weighed by the passing of time and yield an experience of time condensed within a single frame composition.

Still from Trip (1972)

Even in his other films, where the State mandates became much more pronounced, Pati managed to explore the cinematic medium in his own individualistic style. Pati’s films on family planning, such as Claxplosion (1968) and Six Five Four Three Two (1968), are interesting examples of the complex negotiations between the official mandate and the film text and form. Claxplosion uses the pixilation technique and electronic music to show an artist struggling to make a sculpture. Finally, he makes a sculpture of a couple with two children. The camera then moves onto the reference image used for the sculpture, which has a couple with five kids and strike-off marks on the other three. The film directly makes a point about the State’s promotion of family planning with two kids per couple.

Still from Claxplosion (1968)

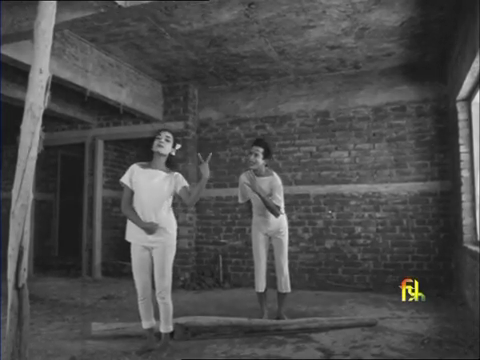

The same minimalist aesthetic is visible in Six Five Four Three Two. Here, the filmmaker chooses a construction building as a site, where two mime artists act as a couple that are planning their family. While deciding how to organise their prospective home, the husband hints at six children, but the wife says two. The negotiation continues as the husband hints at five, but the wife still says two. Finally, after a long discussion, they decide to have two children and the couple seems happy. The mime artist Irshad Panjatan’s dexterity, the starkness of the location of the set and the simplicity of the topic—all of these factors make the film an interesting experiment within State-mandated film, just like the use of sculpture and an artist in Claxplosion. Thus, these films do not merely remain films about informing and educating the masses; they become important cinematic negotiations with the filmic medium and the mandate or use attributed to the film.

Still from Six Five Four Three Two (1968)

Exploring the interiorities and experimenting with newer forms of cinematic renderings and techniques, Pati’s “madness” can be seen as a microcosmic spirit of the time at FD. His films symbolise the changing face of documentary film practice in India. Reading his work today, Pati remains relevant not only in terms of being the pioneer of techniques like pixilation but also for his phenomenological explorations of the medium within the framework of a government organisation.

In case you missed the first part of this essay, you can read it here. To read more about experiments within the film form, read Ankan Kazi’s study of Ayisha Abraham’s work. See also Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Still City (2017), which responds to the city streets of Mumbai.

All image stills from films by Pramod Pati. Images courtesy of the author and Films Division.