Following the Rhino: On Sahil Naik’s Karkadann of Land and the Dark Seas

The Goan artist Sahil Naik’s film Karkadann of Land and the Dark Seas (2023) considers the fate of the rhinoceros in history. The work starts with a mysterious, early mythical account of a people gaining enlightenment in the woods and finding a “beast” that carried an anthill on its nose, which “walked in a straight line, trampling the growth and paving a pathway.” From these impressions, Naik moves on to focus on three recorded instances of the animal’s encounters with Europe.

Karkadann of Land and the Dark Seas seeks to investigate architecture as “witness” as well as “evidence”—including the symbolic structures adopted by myths as they seek to enter the domain of history. Both aspects come together in the form of the rhinoceros, seen as an exotic object of exchange between Europe and India. It symbolises a difficult, ongoing relationship built on wonder, curiosity and distrust, all underwritten by violence. Naik traces the fate of the rhinoceros as a passive witness to history from a mouldering lighthouse built centuries ago (in the Fort Aguada, to guard against the Dutch) that directed incoming vessels from Europe, to the Roman Colosseum that witnessed mass animal (and gladiatorial) slaughter under the rule of Philip the Arab, which also saw a solitary rhinoceros caught up in the violence. The animal serves as evidence of the mysterious ways in which it has witnessed the unfolding of history and even shaped it. Reflecting on a much-restored mural image of a rhinoceros in the chapel of Our Lady of Good Voyage, Naik suggests that the animal had become an abstraction by that point: “it is a spectre, evidence and speculation.”

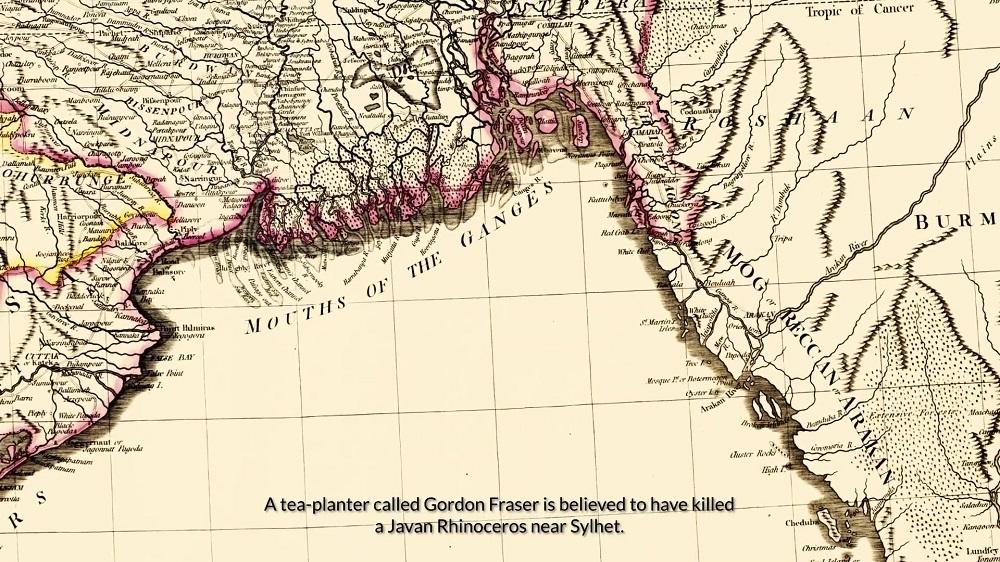

Rhinoceroses may have existed during the Harappan period and in more diverse landscapes than previously imagined or observed. The animal leaves traces of its existence behind in archaeological objects (some dating back to the Harappan period) that tease the line between myth and reality, asking us if these were seen in the mind’s eye or through the naked eye. A rhinoceros that was sent to Portugal on the ship Nossa Senhora da Ajuda found celebrity in Europe as a result of the famous woodcut made by Albrecht Dürer, which was reproduced across the continent. The artist had not seen the animal himself but had created the image from written descriptions, resulting in a confection that expressed a battle-hardened animal-knight in steel armour instead of what the rhinoceros actually looked like. The surrealist artist Salvador Dalí was said to be obsessed with rhinoceroses as well, seeing their shape and beauty in everything anyone says in his brief (fictionalised) cameo in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris (2011). Dalí would go on to make sculptural installations featuring the rhinoceros’ horns, which he saw as “indeed the legendary unicorn horn, symbol of chastity” (as well as violence), and valued for its logarithmic spiral. One can see this as a surreal dream work that took its cue from geometry, forging an essential link between fantasy and science that underwrote several chapters of European modes of knowledge-formation under conditions of colonial contact with unknown lands (and people and creatures) in the East. Naik wonders if the rhinoceros is a figment of our imagination, much like Dalí does, restoring wonder as another essential mode of apprehending the exotic and those that are only partially known.

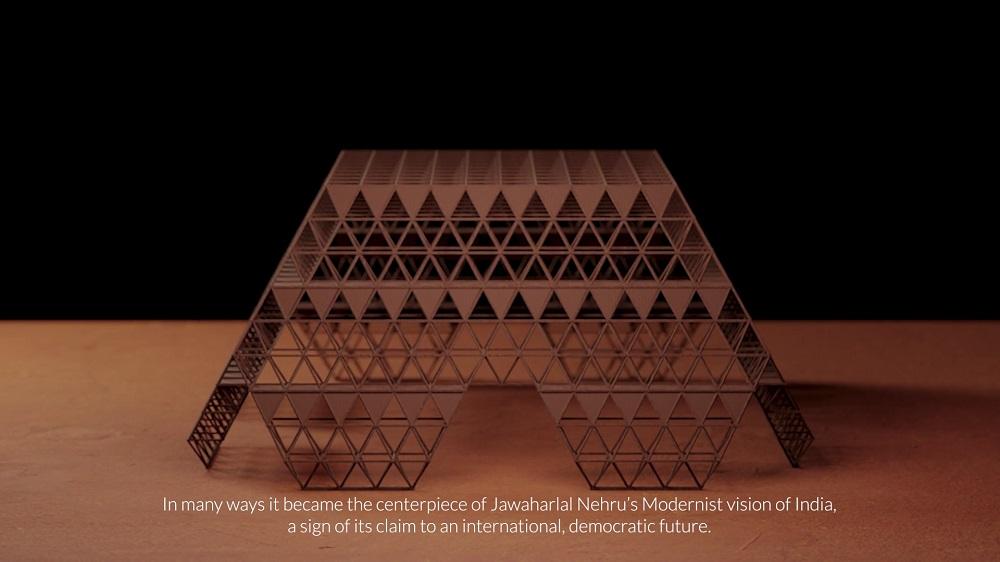

Another historical frame that Naik appends to his investigation of the rhinoceros is the transition of the Indian state’s ideological moorings. This shift can be tracked from Nehruvian visions of scientific achievement and the building of institutions like the National Museum of Natural History in New Delhi (which has a rhinoceros image as its official logo) to a post-2014 era of obscurantism, which witnessed a mysterious fire gutting the Museum. In Jawaharlal Nehru’s post-independent secular, non-aligned India, architecture (and politics) were said to have embraced futurity, and “The rhinoceros became a symbol of strength and forging an independent path. For the rhino treaded the untrodden.” As evidence of the rhinoceroses’ influence on this futurism, the film points to the famous Hall of Nations built by Raj Rewal and Mahendra Raj in New Delhi’s Pragati Maidan for hosting international expositions (it hosted the 1972 International Trade Fair). The structure prominently featured horned ribs, or truncated triangles, which are reminiscent of the form of the rhinoceros horn.

A certain mode of embodying the imagination of the future, as one that is full of risk and the promise of uncertain reward, has been reversed since then. Naik’s subtitle text informs us, “Since 2014, several modernist structures have come under attack and have been demolished in a concerted attempt to erase Nehru’s legacy.” Following the fire that destroyed most of the possessions of the National Museum of Natural History, the film points out that the humble gainda (rhinoceros) that was lodged in the Museum survived the fire “possibly as one of the witnesses of this scene of crime.” Its resilience proves, in the end, that even as history stumbles into the domain of the strange, the rhino’s skin will probably be able to endure it—and, from an unbearable present, perhaps speak to an unimagined future to come.

To read more about ecological visions that reimagine the past and future, revisit Najrin Islam’s essay on Himali Singh Soin’s static range and Annalisa Mansukhani’s reflection of Tejal Shah’s horned creatures in Between the Waves.

All images from Karkadann of Land and the Dark Seas (2023) by Sahil Naik. Images courtesy of the artist.