In Search of Paradise: Bawa’s Garden by Clara Kraft Isono

Mediated by a slow unravelling of history and memory, Bawa’s Garden (2022) by Clara Kraft Isono follows the work of renowned Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa. The feature-length documentary film is being screened as part of the 12th Dharamshala International Film Festival 2023. Led by its unnamed protagonist—a young woman searching for Bawa’s famed estate and beloved home, Lunuganga (Sinhalese for salt river)—the film opens up gentle encounters with people and places in fond remembrance of Bawa’s life and the sheer expanse of his work.

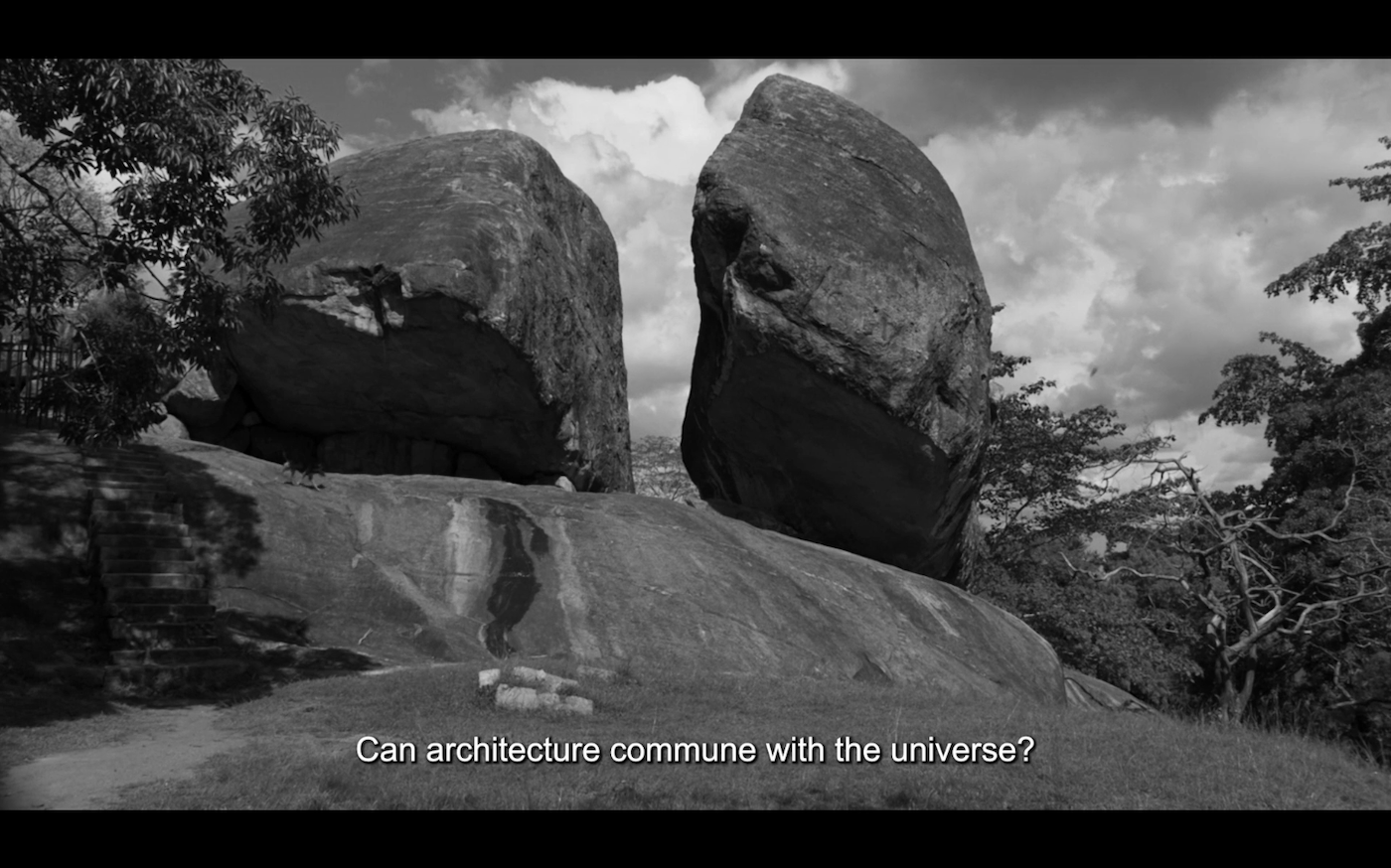

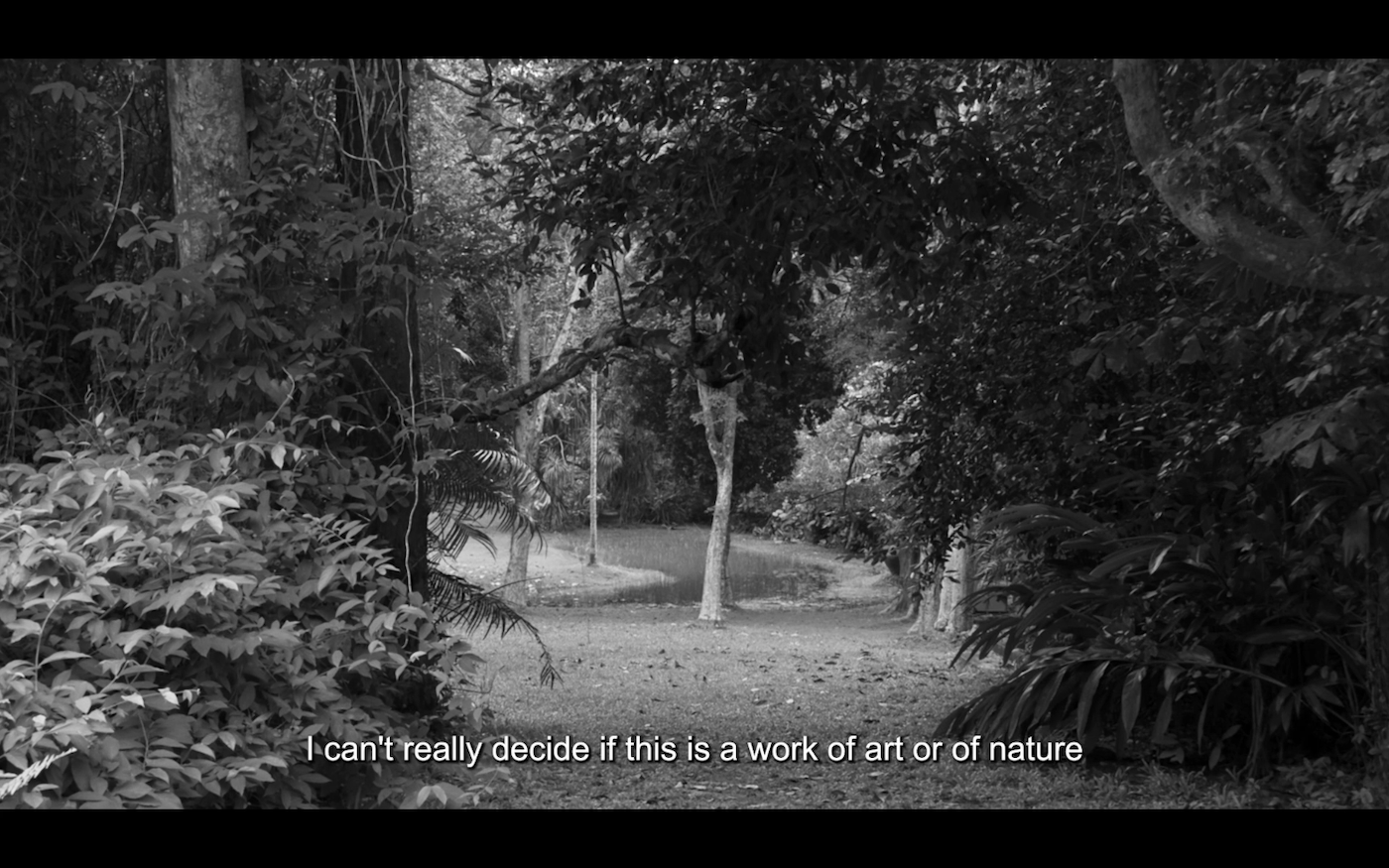

Isono treats us to a staggered narrative, orchestrated through fifteen chapters—“Beginnings”, “The Visitor Book”, “The Spirit of the Place”, “The Past”, “The Rain”, etc., to name a few—that isolate moments from Bawa’s life, his buildings and their inhabitants, captured across spectacular frames in vivid hues and stark monochromatic splendour. Over the course of the film, we are introduced to Bawa’s lifelong fascination with gardens, an infatuation that plays out in the designs he conceived and executed and their relationship to the surrounding environment. Bawa’s visions for space-making are illustrated with a few examples: the hotel in Kandalama is a monumental work of visual and spatial choreography, activated and sustained by its climate-responsive architecture and integrated seamlessly into the untouched landscape. The chapel in Bandarawela, a deeply evocative space for prayer and contemplation, is made even more profound by Bawa’s careful use of local material, adapted to conjure an atmosphere of serenity for the community.

Keeping with a certain poetics of architecture, Isono’s film centralises the experiential in its efforts to map in immense detail Bawa’s practice. Akin to the logic of Bawa’s own creative strategy—slow and recalcitrant in its approach, reluctantly aware of and distinctly moving away from the spectre of over-explanation and hyper-definition—the cinematography is immersive, paying homage to his predilection for the same, indicated by the largesse of his structures and spaces. Isono ensures that beauty as a notion, trope, form and frame is unmissable and unmistakeable in its representation and interpretation across the film.

“Bawa wanted us to look. To look out from within.” In this excerpt from the voiceover, Isono highlights yet another important tangent: the question of position and inherent positionality. Bawa’s lineage and privileged upbringing find brief mention within the scope of the film, but Sri Lanka’s turbulent colonial past remains a citation in the background, open to the viewer to delve deeper into. Isono maintains that Bawa was more than just an elite eccentric, as these perspectives briefly open up a more complex lens—one that adds to our understanding of his rootedness as well as his alienation, shedding light on his associations to the landscape without taking away from the dreamscapes he crafted with immense care.

One of the later chapters, titled “The Women of Aluwihare,” looks at artist and textile designer Ena de Silva’s house in Colombo, which was built by Bawa in 1962. The house became a space for gathering alongside de Silva’s batik-making practice. Here, Isono also mentions the weaver and colourist Barbara Sansoni and artist Laki Senanayake, with whom de Silva worked in close collaboration, along with Bawa. de Silva’s efforts at community empowerment culminated in a women-led cooperative, something that Isono connects to Bawa and his ability to encourage people to “value their disappearing traditions.” In the latter half of the film, in a section focusing on Senanayake, a contributor to one of Bawa’s buildings in Galle, one senses the mingling subtleties of friendship, awe and inspiration. These episodes mark an interesting segue in the reading of Bawa’s socio-cultural influence outside of his architectural contributions, offering us a perspective into his role as a pivotal node in the expanding fabric of Sri Lanka’s development.

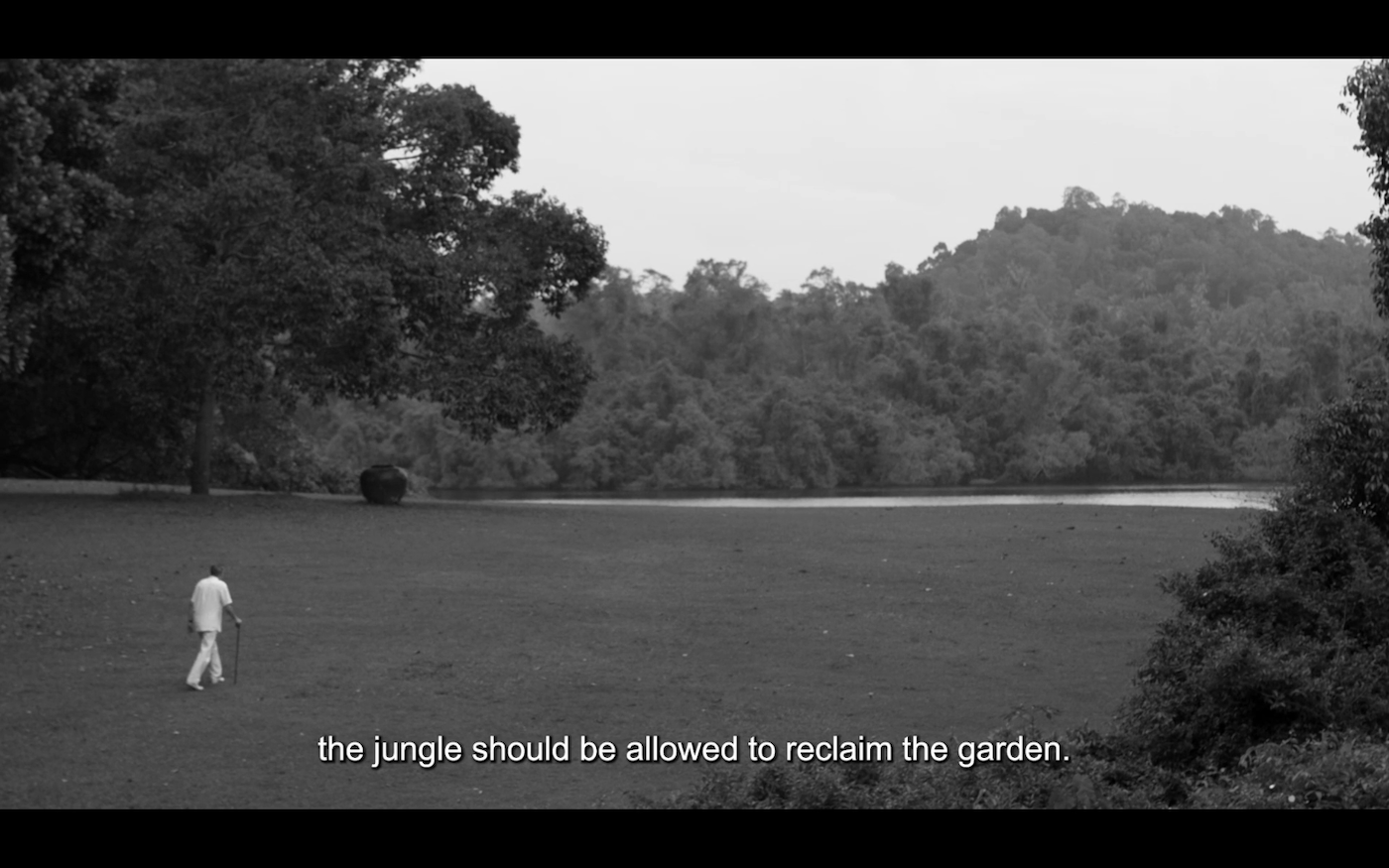

The film asks a question soon after the one-hour mark: “What did he see that others missed?” It is made apparent to the viewer that Bawa did not build for posterity; he built for pleasure. He built not for the megalomania that persists in leaving a mark on a landscape but instead persevered towards the eventual subsumption of everything into the nothingness of nature—true supremacy lay always with the vines, leaves, boulders, light and air. A friend and collaborator, the architect Anjelandran Chelvadurai, states succinctly, “Geoffrey never taught architecture. He had his own methodology, which, if you were close enough, you could learn from.” It is difficult to produce alongside the weight of history and the scales of the past; it is even harder to comprehend and respond with immediacy to the exigencies of the present. During a conversation in the film, Chelvadurai speaks of how gardening is not about what you grow but what you cut. As he recollects his memories of Lunuganga, he remembers distinctly the four-month-long pruning cycle for the garden that would lead only towards the inevitability of having to start all over again. This extends to how we might also read Bawa’s intentions with each site of creation; a proclaimed “outsider,” he worked with and towards absorption—complete and utter surrender, renewed each time around as though a loyal, reciprocal friendship with the landscape.

In the closing scenes of the film, the protagonist asks locals in and around the area about Lunuganga, “Do you know the place? Have you been there? How does one get there?” Lunuganga always remains just out of reach, skirting the fence of certainty. In some way, this mirrors the opening proposition in which Isono places before us the possibility of having this film be many things in itself—a record of movements, a study of hope, a dissipation of form and meaning—something Bawa desired his buildings would succumb to, something Lunuganga eventually did.

Geoffrey Bawa spoke to a contemporaneity that he helped shape definitively with his understandings of language, material, form and function. He saw great potential in the most simple acts of looking, a sentiment demonstrated through his experiments with objects and spaces in conversation with each other. In the concluding verse of his Sabbath poem IV (1983), Wendell Berry writes, “Unmaking makes the world.” For Bawa, domesticity and wilderness did not remain binaries, much like ideas of the inside and outside; they were merely provocations for him to think through, create against and be with, gradually tending towards dissolution.

To learn more about ASAP | art’s special coverage of the films being screened as a part of DIFF 2023, read Santasil Mallik’s essay on Rapture (2023) by Dominic Sangma, Ankan Kazi’s piece on Which Colour? (2023) by Shahrukhkhan Chavada.

All images from Bawa’s Garden (2022) by Clara Kraft Isono. Images courtesy of the director and the Dharamshala International Film Festival.