Searching for Colour: On Shahrukhkhan Chavada’s Kayo Kayo Colour?

Shahrukhkhan Chavada’s debut feature, Kayo Kayo Colour? (Which Colour?, 2023), observes the lives of a Muslim family in Kalupur, an old ghetto in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. The film is a part of the programming at the Dharamshala International Film Festival, 2023. Kayo Kayo Colour is a children’s game where a “denner”, or one of the playing children, announces a colour, which the other players then have to seek in their surroundings. The film is shot entirely in black-and-white, serving as a constant reminder of the community’s continuing search for richness, variety and fulfillment in their lives.

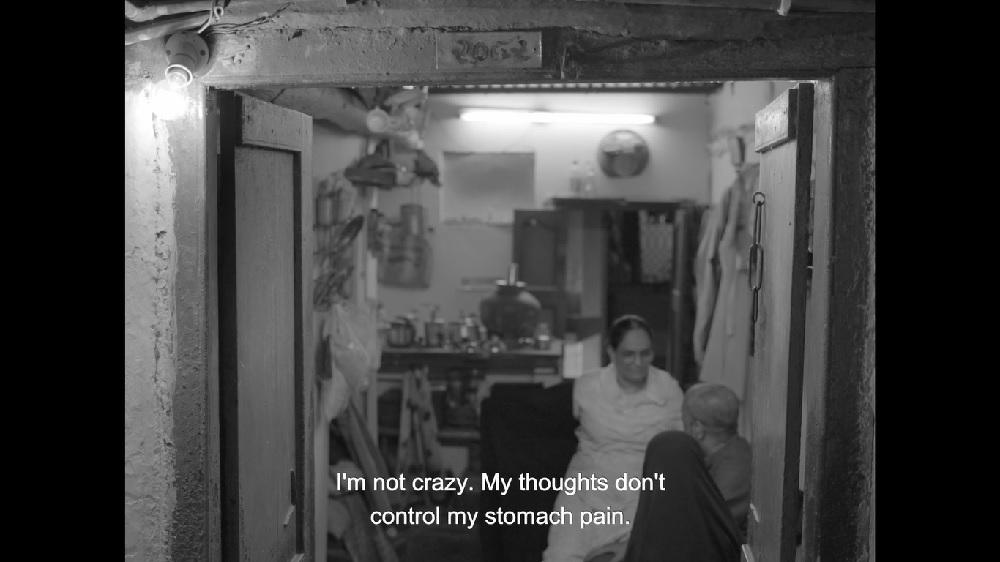

Displaced by the Naroda Patiya riots of 2002, where mass violence was committed upon members of the local Muslim communities by organised political outfits allied to the ruling government in the state, all visceral signs of trauma have been seemingly contained by the veneer of everyday problems—unemployment, downward mobility, and small consumerist fantasies that seek to hold desperately on to an eternal present. Old men still get mysterious upset stomachs, however, rendering them incapacitated and incoherent. The year 2002 is stamped ominously upon the threshold of a door, like writing fate upon one’s forehead.

The men in the film are either reduced to silence or hopelessness by the precarity of gig economies. Razzak’s attempt to take control of his source of livelihood, by purchasing an autorickshaw, instead of doing regular office jobs, results in repeated frustration. This percolates into the lives of his wife and children, but the latter are arguably the central focus of the film’s loose narrative. Their rituals seem to ground the family into a modicum of calmness, even as women continue to do most of the work around the house and struggle to manage their monthly household budgets. The children attempt to help, occasionally distracted by their own problems or enchantments. Plagued by a shoal of sisters, young Faiz faces the wrath of his male friends, who consider him a “sissy.” Ruba, one of the sisters, has her heart set on a particularly expensive, fizzy drink that is called “Drocola”—a beverage that drinks your blood even as you drink it. A particularly eccentric sister is given charge of selling vegetables on the side, which she does by giving some of it away for free to her familiars. Razzak’s mother reminisces about her absent husband with her daughter (who has married into more solvent circumstances)—tracing their misfortunes back to the riots, when their cycle of displacement and depredation began. Lacking closet or storage spaces, their houses are choked with objects scattered all over the floor and under the beds, like a series of wounds open to the gaze of whoever might visit (although no one really does). The neighbourhood wallows in a similarly extended manner, as goats root for food among ruined construction material and boys fight rooster against rooster.

The fiction of the film is a stage upon which reality can unfold. This is often suggested formally, as the actors, all “non-professionals”—and residents of Kalupur—frequently improvise dialogue, stare directly at the camera (that classical Indian cinematic act of witnessing a potentially critical audience and dressing them down into something more akin to a feckless bystander), or conjure up a pleasantly confusing chatter-scape of overlapping sounds. The scope of everyday troubles that ail the family of Razzak, Raziya and their children is traced over the course of two days. Its shock ending allows us to date the events of the film to a couple of days in November 2016, when demonetisation wreaked further havoc on communities stranded without the support of regular state aid and financial security. The “shock” appears to be a slight one—but the film accumulates so many small layers of experience, repressed desires and economic frustration that it acquires an emotional heft that regular, sympathetic and well-meaning films depicting Muslims as victims of stereotypical violence tend to miss out on.

To learn more about films being screened at the 2023 edition of the Dharamshala International Film Festival, read Santasil Mallik’s review of Dominic Sangma’s Rimdogittanga (Rapture, 2023). To read more about moving image works that have examined everyday lives after conflict, read Sukanya Deb’s essay on Desire Machine Collective, and Ankan Kazi’s essay on short documentary programming by Vikalp, tracing communal polarisation in Uttar Pradesh.

All images are stills from Kayo Kayo Colour? (2023) by Shahrukhkhan Chavada. Images courtesy of the director and Dharamshala International Film Festival.