Conversations with the City: On Dreams of a Summer Past

Spaces of dwelling are prone to perpetual transformation, making them integral subjects of the archive. Tapping into the intimate memories of their beloved city of Bengaluru, three lens-based artists—Indu Antony, Krishanu Chatterjee and Vivek Muthuramalingam—trace episodes of their lives enmeshed with the city in the recently concluded group exhibition Dreams of a Summer Past at Blueprint12, New Delhi. The artists collaboratively run Kāṇike, a community-based artistic space in Bengaluru, encouraging diverse forms of image-making through organic and analogue processes. One of the driving principles behind their initiative is to create “…a space to indulge in conversations.” This conversational approach is mingled with an experimentation with alternative printing techniques—cyanotype by Antony, gum oil by Chatterjee and albumen by Muthuramalingam—to capture lived experience through resulting monochromatic photographs of the city’s architecture, culture, individuals and communities in all their essence.

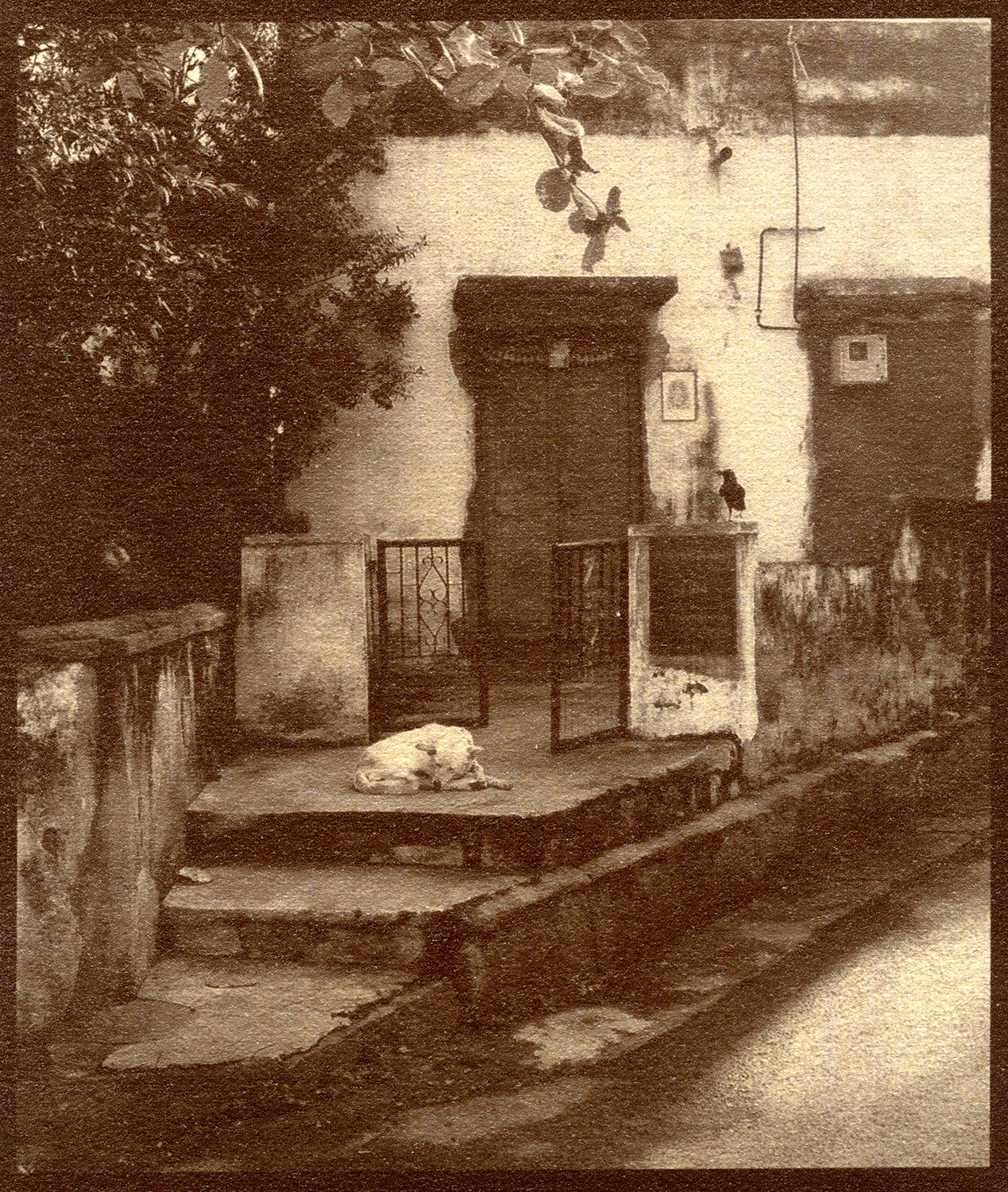

Gandhi Bazaar, from the series Visage in the Dark (Vivek Muthuramalingam. Bengaluru, 2023. Albumen Silver Print, Gold toned on Fabriano Rosapina paper.)

Through an interplay of images with textual and audio narratives, along with the exhibition texts that provide a glimpse into artists’ narratives and older printing processes, the viewer is familiarised with acts of archive making. Deconstructing the city, the artists explore the fragmentary nature of memory through disruptive juxtapositions in their photographic series. While Muthuramalingam employs handwritten text with his shots of the city, Antony embeds printed text in her works along with personal family photographs. As an aural intervention, Chatterjee accompanies his photomontage with an audio narrative.

Bengaluru, as represented in the exhibition, is not the quintessential reflection of “modernisation”—glass arcades, high-rises and airports. The region where modern Bengaluru is situated has witnessed the succession of several kingdoms throughout the centuries, contributing to the influx of diverse communities from around the surrounding territories, especially from the sixteenth century onwards. Its oldest areas, called “Petes” (areas of different trade activities), were established during this time period by Kempegowda I. We come across two of these neighbourhoods, Cottonpete (cotton market) and Akkipete (rice market), in their contemporary mixed forms in Muthuramalingam’s albumen prints. For the artist, old places within these expanded multi-ethnic regions contain the “real” essence of the city, still accommodating a large number of local, small enterprises and hybrid cultures, which are holding their ground in the face of IT boom, the headquartering of big conglomerates as well as unicorn startups and tech parks that flourished by the end of the twentieth century.

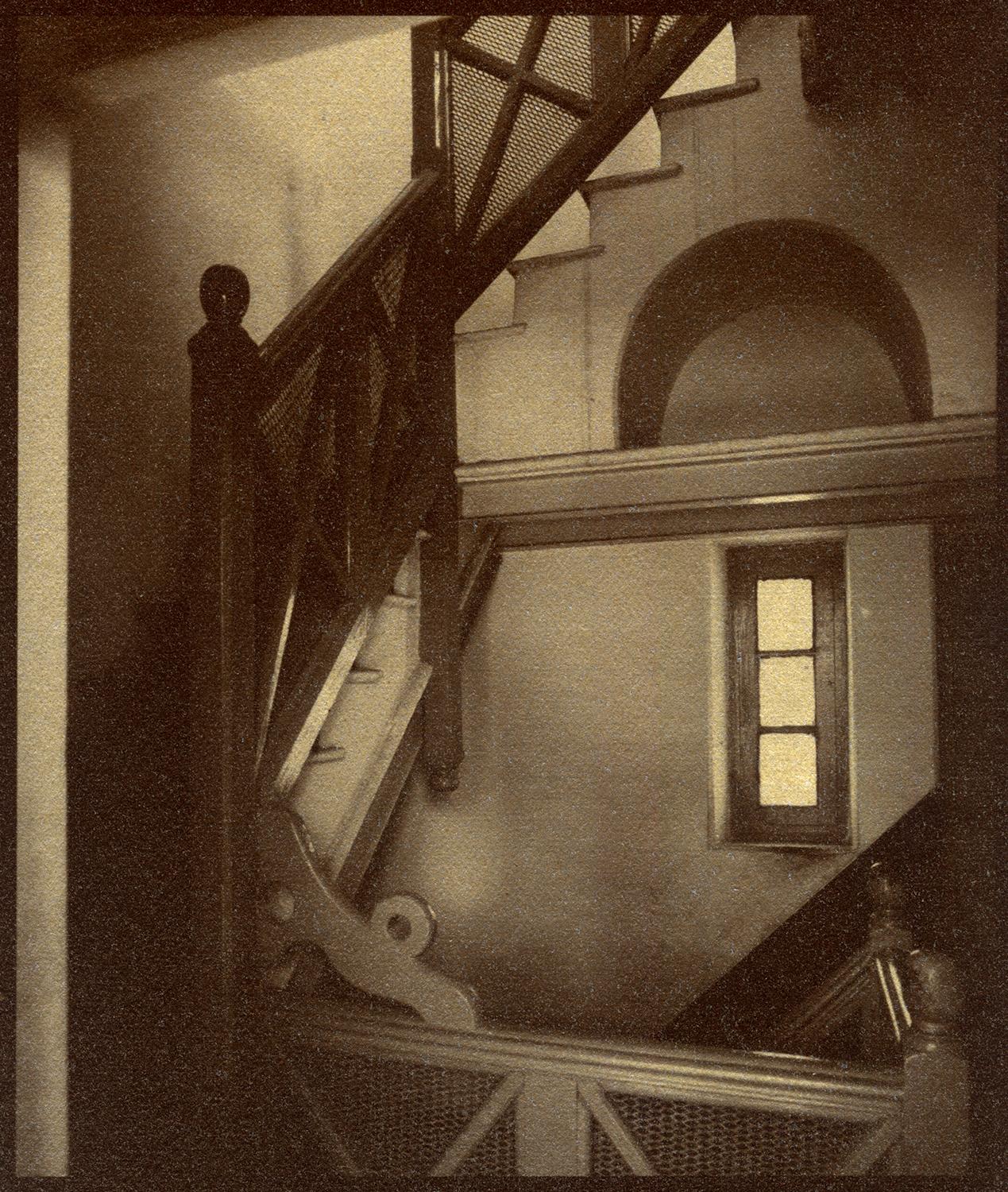

CVMS Hostel, from the series Visage in the Dark (Vivek Muthuramalingam. Bengaluru, 2023. Albumen Silver Print, Gold toned on Fabriano Rosapina paper. Albumen Silver Print, Gold toned on Fabriano Rosapina paper.)

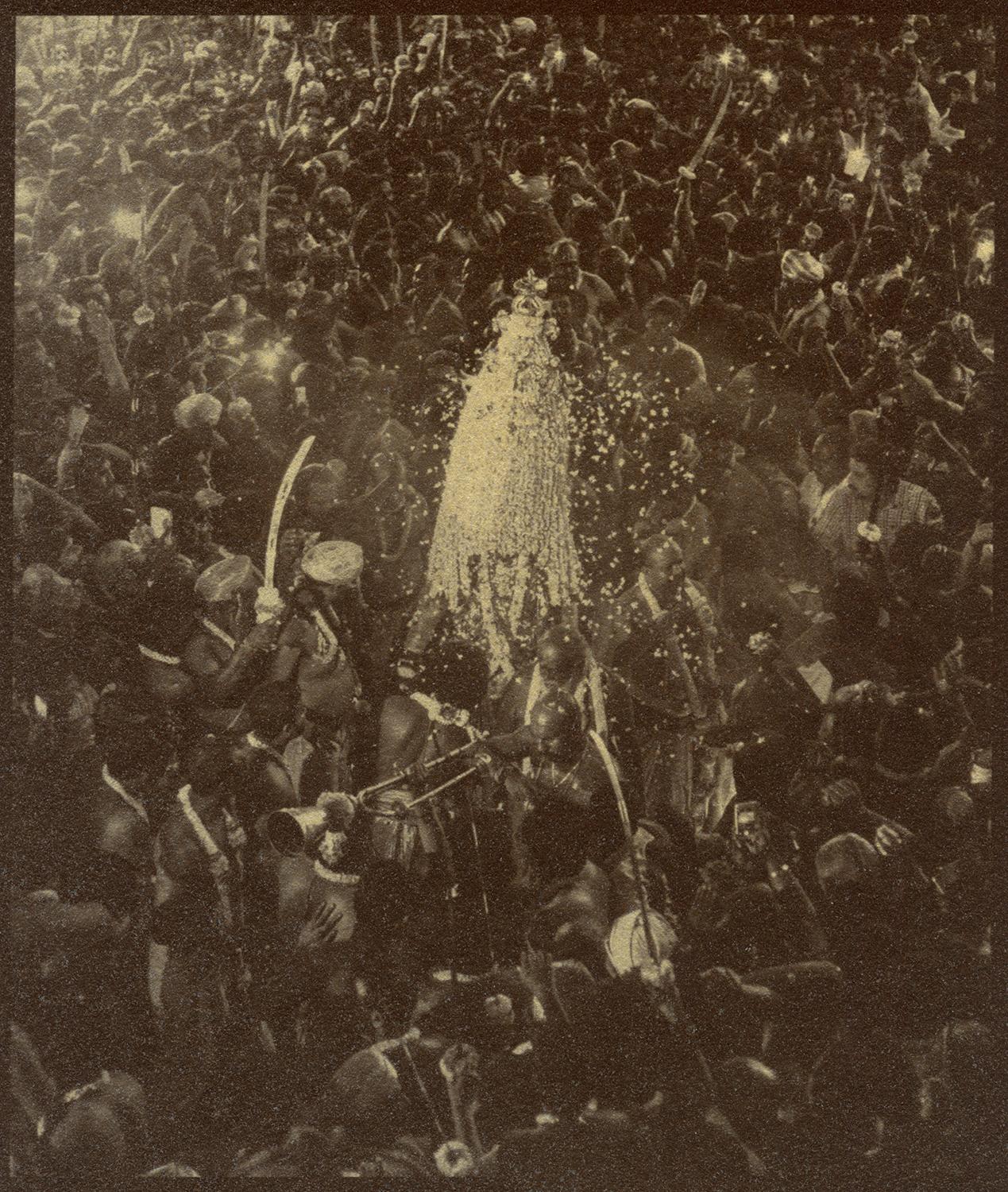

Muthuramalingam’s great longing for the old Bengaluru comes out vividly in the antique appearance of the albumen silver prints titled Visage in the Dark (2023). Their tonal range turns these contemporary images into a distant past that has to be revisited to inform our present and future. The handwritten texts accompanying the images offer insights into the experiences of the artist within the spaces and the communities he engages with. His long walks along the lanes and streets take him to places such as old houses in Basavanagudi. Instead of the facades of “Silicon Valley” Bengaluru, we are transported to Hotel Vandana; the farmers in Bellandur; Karaga festival; Christmas in Lingarajapuram; Tipu’s armoury; Chintalapalli Venkatamunaiah Setty’s Free Boarding (CVMS) hostel that provides affordable housing to students from other regions; and his last outing in 2020 at Avalahalli State Forest, apart from other nooks and corners of Bengaluru that may otherwise get lost in the bustling life of the city.

Karaga, from the series Visage in the Dark (Vivek Muthuramalingam. Bengaluru, 2023. Albumen Silver Print, Gold toned on Fabriano Rosapina paper.)

Installation view of Visage in the Dark series (2023) by Vivek Muthuramalingam.

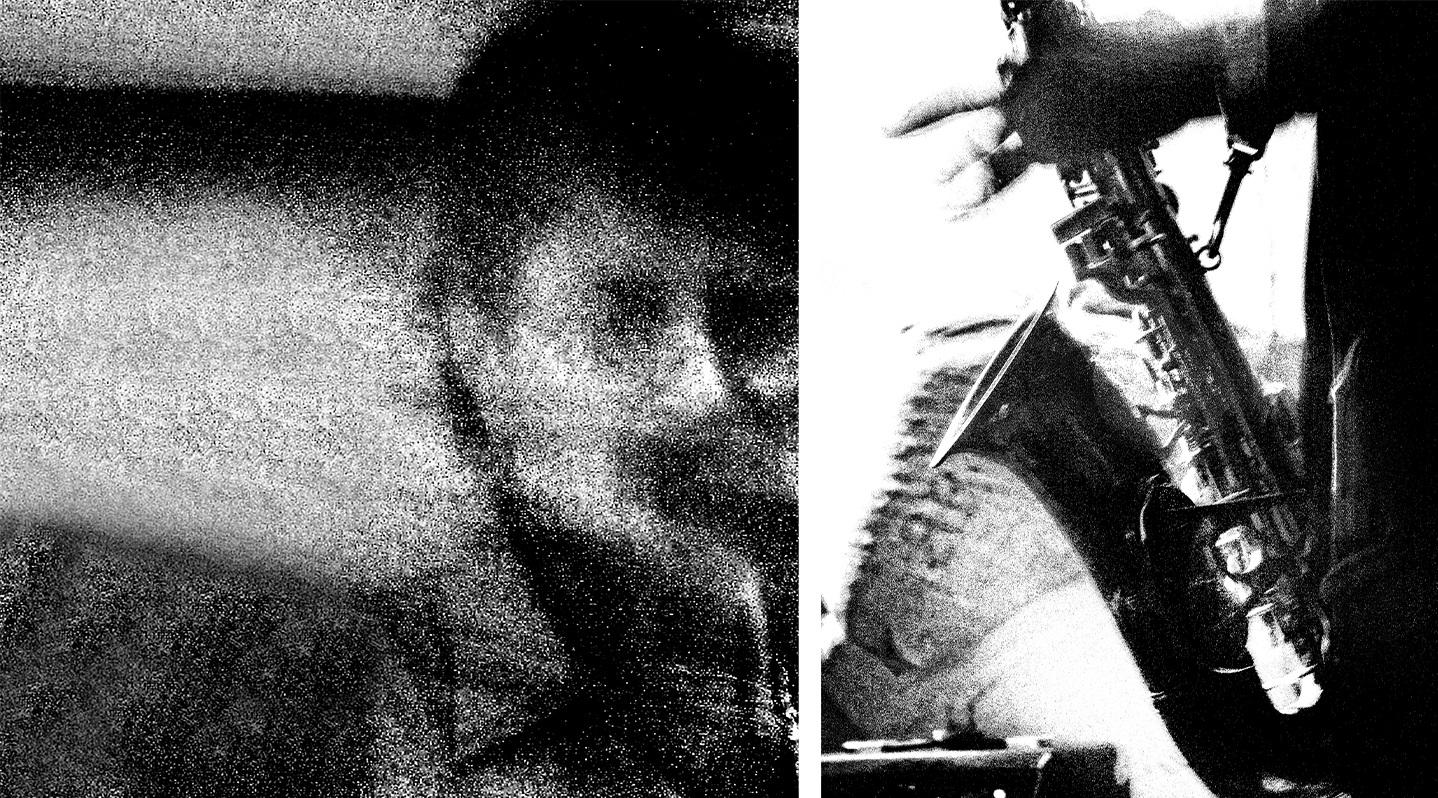

In the three-part montage of gum oil photographic prints by Chatterjee titled So What (2023), an era of Bengaluru’s city life from the 2000s is recounted through “JC” or the Java City café. The oblique frames and blurred shots, capturing the movement of people and objects alike, reflect the ephemerality of such mundane moments. The charcoal-like quality of the prints accord them a painterly aesthetic. The mood of the jazz music and the environment it created in the café are enhanced by the noise and grain of the photographs, making them rhythmic in their visuality. They seem to dissolve into each other like fading memories of the relationships he had developed there, which helped him belong to the city as a new migrant. Through the work, Chatterjee contemplates the building of communities through conversations within spaces of public access such as JC.

So What XXXVI (Krishanu Chatterjee. Bengaluru, 2023. Gum oil on Fabriano Rosapina paper.)

L-R: So What XXXV and So What XXV (Krishanu Chatterjee. Bengaluru, 2023. Gum oil on Fabriano Rosapina paper.)

The hour-long audio work titled SO WHAT: Lores of “JC” (2023) accompanying the collages features conversations on Java City café and its culture, with an ambient jazz number playing in the background. A sharp stare, an old camera, table tops, portraits of jazz artists, coffee cups and silhouettes all become animated like ghosts of the past. Navigating through the works, the series immerses us in the life of Java City café, which provided Bengaluru with a unique culture and identity. As time progressed and new cafés came around after 2012, slowly JC got lost. And now, what is left is the nostalgia that is channelled through these hazy photographs. The audio-visual work becomes a reflection on spaces becoming the birthing grounds of cultures that fade in the face of fleeting time. Yet these built worlds remain through memories, where photographs and oral/textual narratives serve as catalysts for concretising their once flourishing presence.

Installation view of So What (2023) by Krishanu Chatterjee.

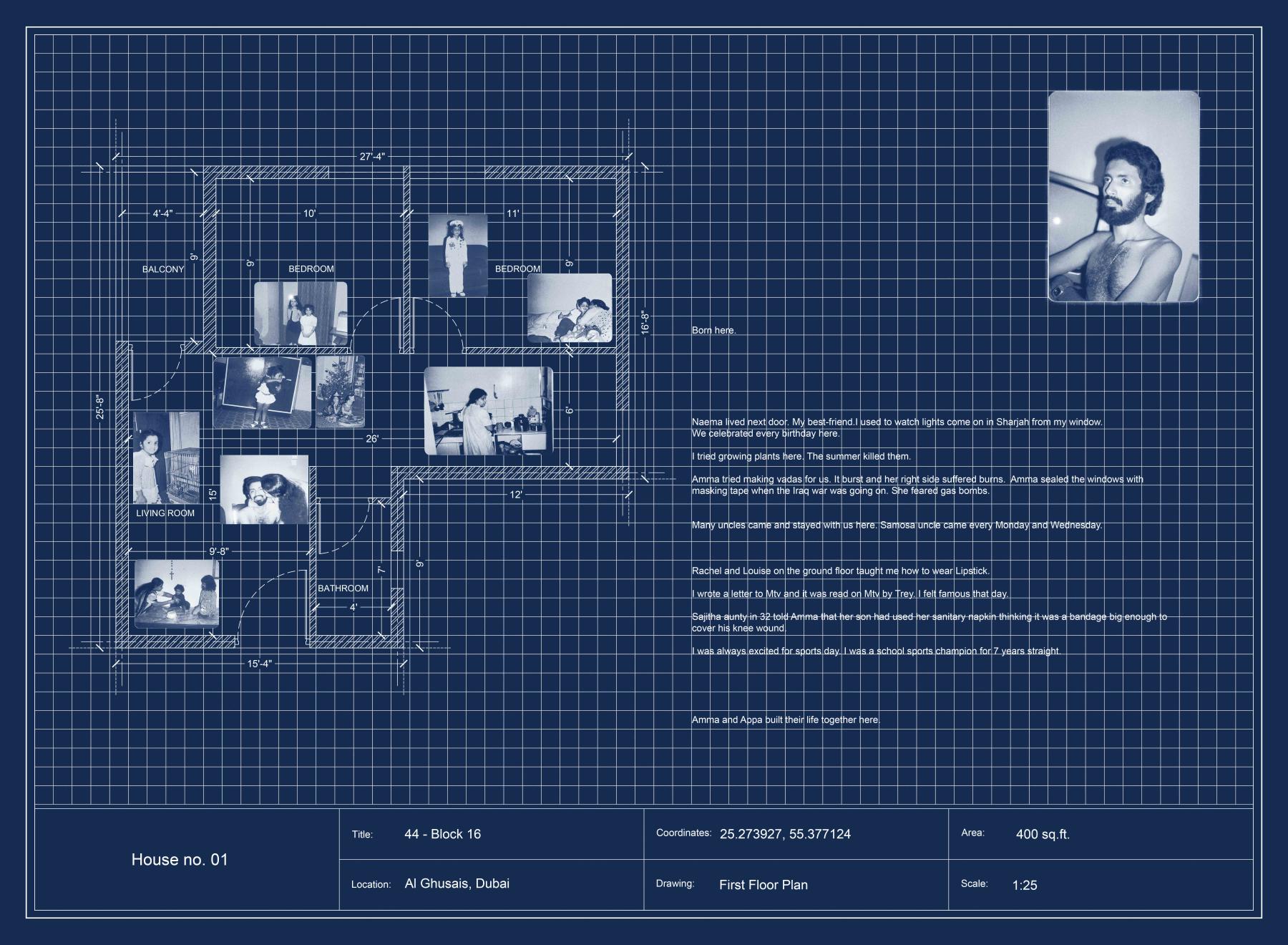

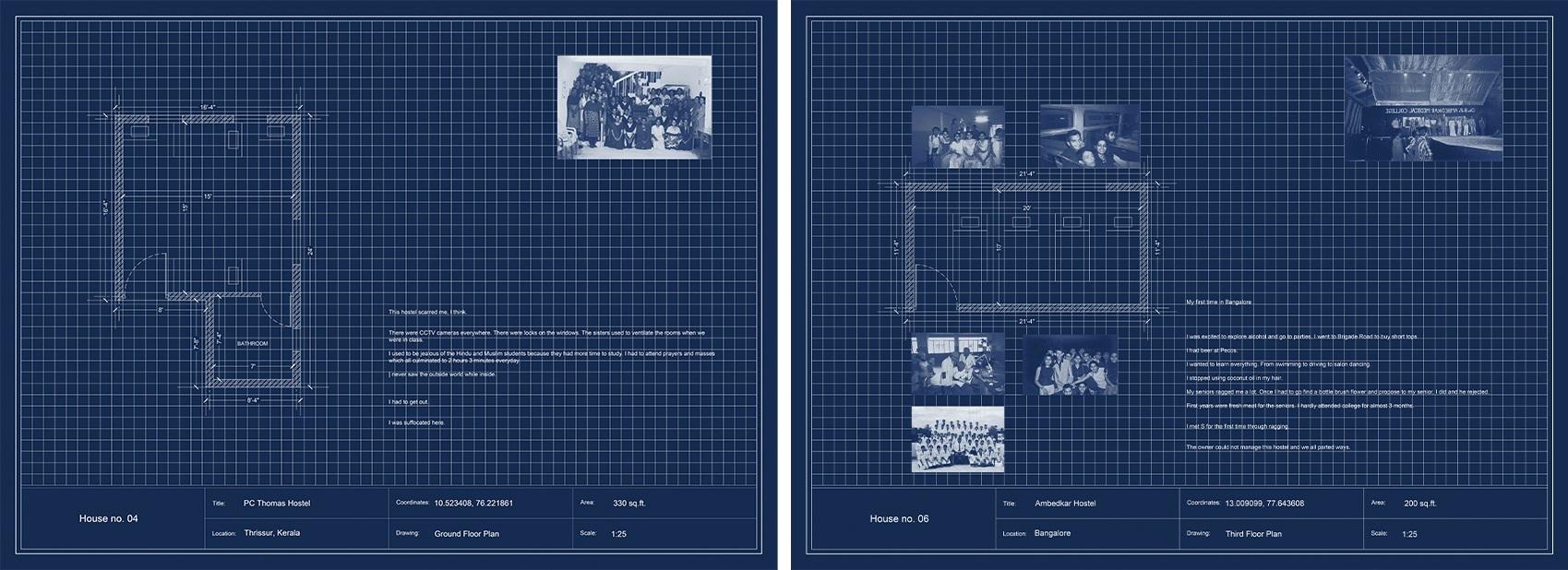

Antony’s series of cyanotype prints, Archive of Memories (2023), explores the city from a deeply personal perspective by intriguingly mapping the contours of her homes and her lived experiences. Each of these blueprints features a technical drawing of the home she has lived in for a specific period of time, such as her home in Dubai, Thrissur and Bengaluru. Old family photographs are embedded in the plan, with one shot stitched with a strand of her hair, symbolising her presence and connection. Antony has been collecting her hair for years now and has turned it into an organic artistic medium to recollect memories and revisit the past. The hair strands also serve as an act of self-representation. The juxtaposition of images with poetic, personal narratives in the form of diaristic text allows us to dive into the artist’s private space. Some people’s names are mentioned by a single letter, while others are mentioned freely. This act of hiding and revealing identities also creates an idea of intimacy of connections that has to be kept encrypted for the viewer while consciously revealing experiences that are an integral part of the artist’s life.

Archive of Memories I (Indu Antony. Bengaluru, 2023. Cyanotype on Saunders 100% rag paper, artist’s hair.)

The timeline of the prints is marked by the changing nature of photographs, from family pictures taken with portable cameras and formal pictures in hostels to photographs taken by Antony of her friends that gradually turn visually experimental. In the print “House no. 04”, there are no pictures in the floor plan except a single image—a formal picture with her hostel mates and teachers—which is stitched. The melancholic tone of the narrative reveals her frustration with the space of the hostel as it bound her, generating feelings of angst and an urge to be free from the authoritative control of religious and traditional customs. The very process directs our attention towards the politics of space through various limits of access.

L–R: Archive of Memories IV and VI (Indu Antony. Bengaluru, 2023. Cyanotype on Saunders 100% rag paper, artist’s hair.)

The exhibition transforms into a multi-sensory bioscope that leads us into the mindscapes of the artists’ visions and versions of the city. Together, the image and text form a visual language that calls for an interrogative reading of the work while problematising the image culture by re-contextualising personal and public spaces. Moreover, the slow and time-investing process of older photographic techniques allows the artists to deliberate on the tactility of handmade prints, which leads to an intimate experience. As an after-effect, our perception of these images is rendered into an embodied experience due to an awareness of their materiality. Challenging existing methods of representation, the artists locate their identities at the intersection of fleeting time and a sustained, accumulated past to rescue the fading memories of the city they inhabit, thereby cultivating new forms of agency and resilience.

To read more about work done by the artists, revisit Hitanshi Chopra’s review of Kāṇike’s exhibition Being in a State of Salax, Anisha Baid’s essay on Indu Antony’s Cecilia’ed and Najrin Islam’s reflection on Indu Antony’s practice.

All images courtesy of the artists and Blueprint12.