Reinventing the Wheel: On Meghnath’s In Search of Ajantrik

Meghnath’s documentary In Search of Ajantrik (2023) revisits the locations where Ritwik Ghatak shot his famous 1958 feature film Ajantrik (The Unmechanical/The Pathetic Fallacy). Seeded by an original short story by Subodh Ghosh, the film was Ghatak’s first to find wide release, even though it “flopped” commercially. Several years after its making, the filmmaker wrote about the ways in which the story spread its roots in his mind since he first read it as a youth who had just graduated from college. Ghatak remarked about his intention to critique the mysterious psycho-social role of the machine and the narrow, conflicting nonhuman part it is usually given to play in mythic opposition to the human. He draws our attention to the importance of the locales in Jharkhand and the presence of members of the Oraon tribe, whose language and culture are presented in stark contrast with the alienated Bengali taxi-driver Bimal, who plies his trade through this countryscape. Ghatak writes,

“The film is, after all, about them (the Oraon), so it could not have been conceived without their participation. The story too is quite simple. If you’re not eccentric enough how would you believe in the central conceit of the plot, where we ask you to imagine that a ramshackle, god-forsaken vehicle could still carry a taste of the human?”

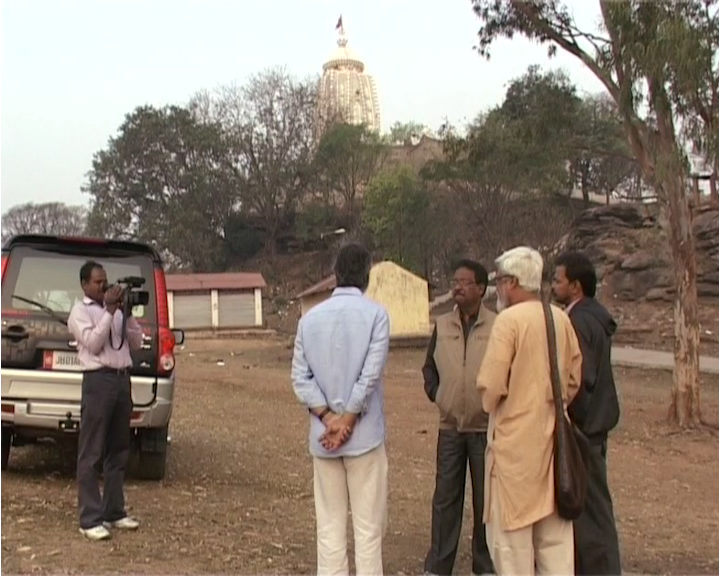

Writers and critics have suggested various interpretations of this relationship between Bimal and his worn taxi, which he affectionately names Jagaddal (the immovable), for its frequent tendency to break down and refuse its ordinary functionality. It is, in other words, more human than an efficient machine—causing him endless agony, but also providing him with moments of comic and emotional relief, as the car occasionally responds with cartoonish noises. Some have pointed our attention to the car’s anthropomorphic presence, while others have seen it as an emblem of modern industry’s propensity to track sideways towards decay rather than stick to the promised, straight path of progress. Meghnath’s film tends towards the second interpretation, anchoring the question of industrial development to the narratives of progress in modern-day Jharkhand. Through discussions with film scholars and activists while travelling towards the original shooting locations and finding much of the landscape transformed by the machinery of industrial mining and road works, In Search of Ajantrik attempts to construct a critical commentary for Ghatak’s film that can restore the radical charge of the original.

Ghatak’s film—and Meghnath’s commentary—is born out of a complex encounter in Indian modernism between the urban and the “folk.” The alienation of urban intellectuals like Ghatak from colonial and then newly emergent postcolonial forms of complicity with world capitalism forced them to look for artistic inspiration from outside the domains of the city. This encounter worked unevenly across the decades. Ranging from simple acts of cultural appropriation to more involved, participatory methods where the agency of the urban artist was freely mixed up with the “surreal” forms of tribal art, these set off newer modes of consciousness and relationships with the world that one inhabited. The traces of this unevenness are visible in the conversations the commentators have in Meghnath’s film as well, as they track Ghatak’s attempt to mediate this relationship between the urban and the tribal-rural. They rightly draw our attention to the importance of a search for home—both as a concept and physical shelter—in Ghatak’s films, which we usually attribute entirely to his feelings about the partitioning of riverine Bengal (Anup Singh’s film on Ghatak, Ekti Nadir Naam [The Name of a River, 2003] focuses on this aspect), which displaced millions of people.

In Ajantrik, the search for home was transmuted into a search for an aesthetic that can embrace the pointedly different worlds—of the taxi driver who loves his car and the members of the Oraon tribe who were the original inhabitants of the land that is now increasingly dispossessed from them. In this scheme of things, the role of the vehicle becomes sharply defined as something poised for obsolescence. However, for that very reason, it is also up for reinvention or re-appropriation into a more positive, life-affirming relationship with the human. It is not simply an opposite of the human, but only appears to be benighted for its lowly, “mechanical” position further on in a contrived spectrum of essences. Ghatak’s emphasis on “eccentricity” was aimed at overcoming this artificial opposition and working towards moulding not just a new cinema but a new audience. This new audience could appreciate the human in the nonhuman and the perspective of the nonurban other, as it was imbued with an active consciousness that worked within the colonised natural landscape. In this manner, he imagined the role that each of these newly liberated conscious subjects could play for an independent country (and cinema). While Meghnath’s film laments the loss of this freshness of vision, it reminds us of a particularly rich moment in a new, postcolonial India, when Ghatak engineered such possibilities for other artists to pick up on.

In Search of Ajantrik is a part of the Kolkata People's Film Festival, taking place between 24 - 28 January, 2024.

To learn more about some of the films being screened at the 2024 edition of the festival, read Ankan Kazi’s reflections on Shahrukhkhan Chavada’s Kayo Kayo Colour? and Santasil Mallik’s essay on Sreemoyee Singh’s And, Towards Happy Alleys. You can also revisit our In Person series which features Arundhati Chauhan in conversation with Shahrukhkhan Chavada and Wafa Refai on their film Kayo Kayo Colour? and Nishtha Jain on her film The Golden Thread.

To learn more about films screened at the previous edition of the KPFF, revisit Santasil Mallik’s essay on Nama Filmcollective’s Don’t Worry About India, Sujaan Mukherjee’s review of Farha Khatun’s Ripples Under the Skin and Ankan Kazi’s reflection on Ajay Bhardwaj’s When the Tide Goes Out. Also listen to Najrin Islam in conversation with Kasturi Basu of the People’s Film Collective.

All images from In Search of Ajantrik (2023) by Meghnath. Images courtesy of the artist.