A Love Letter in Camera: And, Towards Happy Alleys by Sreemoyee Singh

It is inexorable for new cinephiles to experience that sense of reverential delight when they discover the poetic opulence of Iranian cinema, traversing the country’s complex cultural geography through the lenses of world cinema maestros like Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Jafar Panahi and other usual suspects. The same fate befell Sreemoyee Singh more than ten years ago while she was a film studies student at Jadavpur University. Soon, she took up a PhD project around Iranian cinema from the same department, which for her became her passport to visit Iran and interact with artists and filmmakers. Singh’s documentary, And, Towards Happy Alleys (2023), gradually materialised when she began capturing all those enviable encounters during her journey.

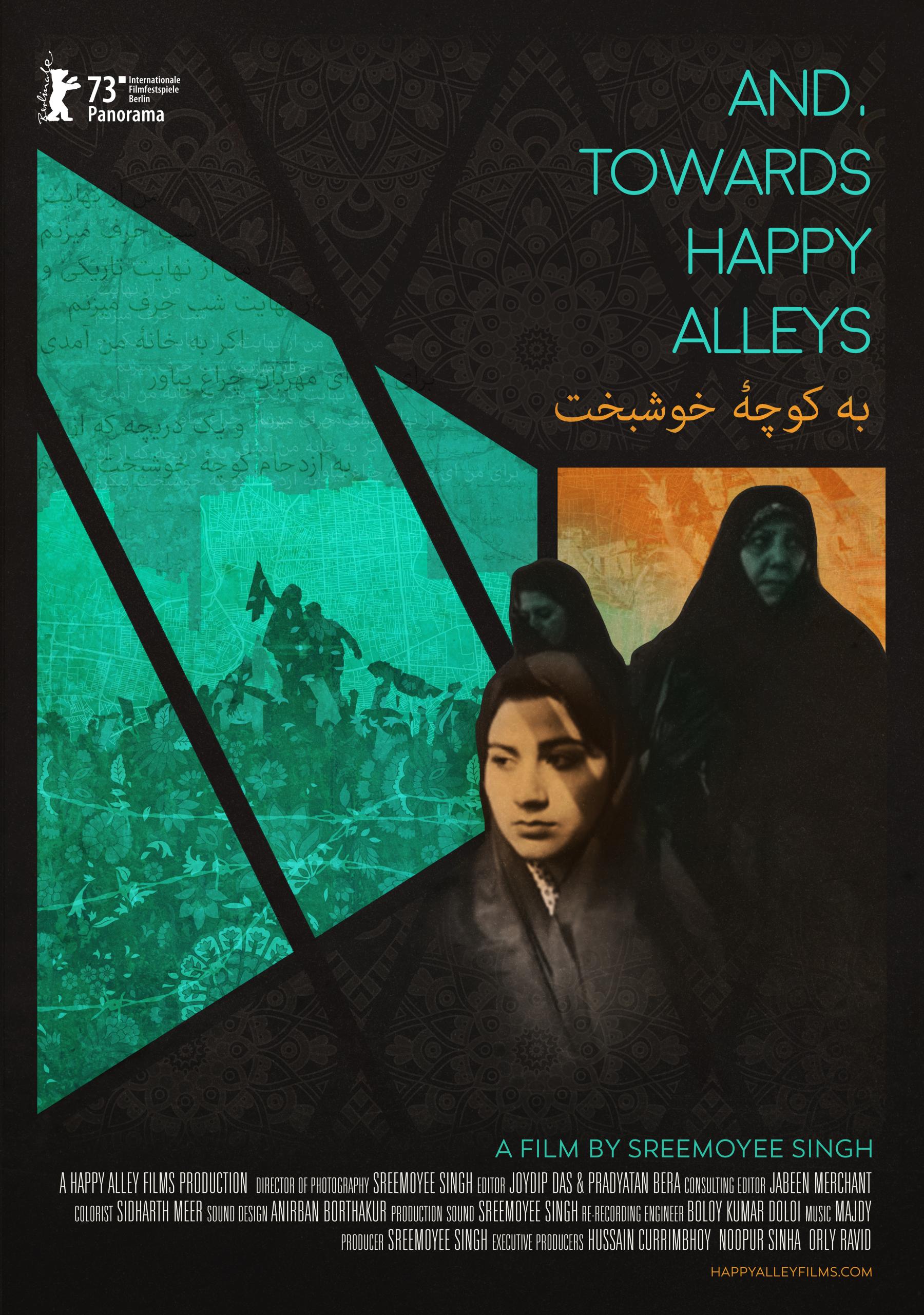

After premiering at the Panorama section of the Berlinale, winning Best Feature Film at BAFICI, and playing at a dozen other prestigious avenues like CPH:Dox, Sheffield DocFest and DMZ Docs, the film reached Indian audiences recently at MAMI and at the 12th Dharamshala International Film Festival. Singh’s creative endeavour is hardly a wryly programmatic documentary exercise and more of, what one might call, a lover’s discourse.

Equally central to her attachment and the film’s concerns is the feminist poetry of Forugh Farrokhzad, whose lines interweaving love, desire and yearning infuses the film’s narrative. Farrokhzad’s poetry comes up in recitations by the author Jinous Nazokkar, from a scene in Kiarostami’s The Wind Will Carry Us (1999), or through the filmmaker’s daily reminiscences in and around the streets of Tehran. Given that Singh’s research looked at “The Exiled Filmmaker in Post-Revolution Iranian Cinema”, it is unsurprising that Jafar Panahi also becomes one of the documentary’s preoccupations. Most of the time, Panahi appears behind the steering wheel as he drives around and reflects on his artistic adventures, almost as if it were a continuation of his film Taxi (2015).

.jpeg)

The pivotal motivation of the documentary is Singh’s enthusiasm for filmmakers and reel characters, those who instilled in her an attachment to Iranian cinema. She slips a letter underneath Kiarostami’s door shortly before his untimely death, has jocular encounters with the maverick Mohammad Shirvani, and engages in a trivia-laden conversation with Farhad Kheradmand, the protagonist of Kiarostami’s And, Life Goes On (1992). And, in a delightful sequence, she catches up with the now-grown-up protagonists of classics like Panahi’s The White Balloon (1995) and The Mirror (1997): Aida Mohammadkhani and Mina Mohammadkhani. Undoubtedly, the characters they played as children are indelible in Iranian film history, arguably as illustrious as Bruno Ricci in Bicycle Thieves (1948) or Tadzio in Death in Venice (1971), classic films from Italian neorealism.

.jpeg)

There is an atmospheric playfulness, laughter and some happy accidents in the filmmaker’s interactions with her subjects, which are not devoid of a critical reflection of Iran’s regressive political regime. Such moments manifest briskly in the film, such as while conversing with Mohammad Shirvani about eroticism in his works, a neighbour’s construction noise inadvertently interrupts them, or her friend Majdy’s musical retreat is cut short by people cutting trees around. These “accidental censors in the city,” as Singh notes, figure like allegories of Iran’s pervasive censorship. More gratifying accidents occur when Singh discovers staying in the same property that Farrokhzad had rented several decades ago. The film’s methodological spontaneity and intimacy also stem from her thorough grasp of the Persian language, which she claims to have imbibed more through Farrokhzad’s verses than through language training. Some of the political questions touching on hijab laws, repression of women’s public expression and the omnipresent morality police are more visibly present in other sections.

1.jpeg)

The shadow of Jin, Jîyan, Azadî (Woman, Life, Freedom), popularised after the institutional murder of Mahsa Amini on September 16, 2022, looms large over the film. Indeed, the film archives several conversations with the human rights lawyer and activist Nasrin Sotoudeh, who was sentenced to 38 years of imprisonment by the regime. A section of the film further explores the contested perceptions around the hijab vis-à-vis women’s autonomy across differing sociopolitical contexts. Local cultural phenomena gather layered densities when Singh politically contextualises them, be it crowds of women watching football matches in shopping malls or Tehran being the hub for nose job surgeries. Yet, none of it is analytically restrictive, as the film wrests free from categorical processes and follows the curiosities and emotional affinities of the filmmaker as an ardent admirer of cinema and poetry in Iran. One might put it this way: Singh has rendered into this film a journey that all Iranian film enthusiasts dream of undertaking.

1.jpeg)

To learn more about ASAP | art’s special coverage of the films being screened as a part of DIFF 2023, read Santasil Mallik’s essay on Rapture (2023) by Dominic Sangma and Ankan Kazi’s reflection on Which Colour? (2023) by Shahrukhkhan Chavada, Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Bawa’s Garden (2022) by Clara Kraft Isono and Mallika Visvanathan’s piece on Clement Town (2022) by LI Kuei-Pi.

All images from And, Towards Happy Alleys (2023) by Sreemoyee Singh. Images courtesy of the director and the Dharamshala International Film Festival.