Collaborative Seedings: Grounded Artistic Practices, Pedagogies and Questions

The latest edition of Colomboscope opened on 18 January 2024, guest curated by Hit Man Gurung, Sheelasha Rajbhandari and Sarker Protick, with Natasha Ginwala as artistic director. Titled Way of the Forest, this iteration of the festival explores ecologies, histories, pasts, presents, and most poignantly, collective and individual relationships with the environments that surround us. Across many exhibition spaces, programmes and platforms, Way of the Forest offers a grounding experience of harmony, sorrow, beauty and strength.

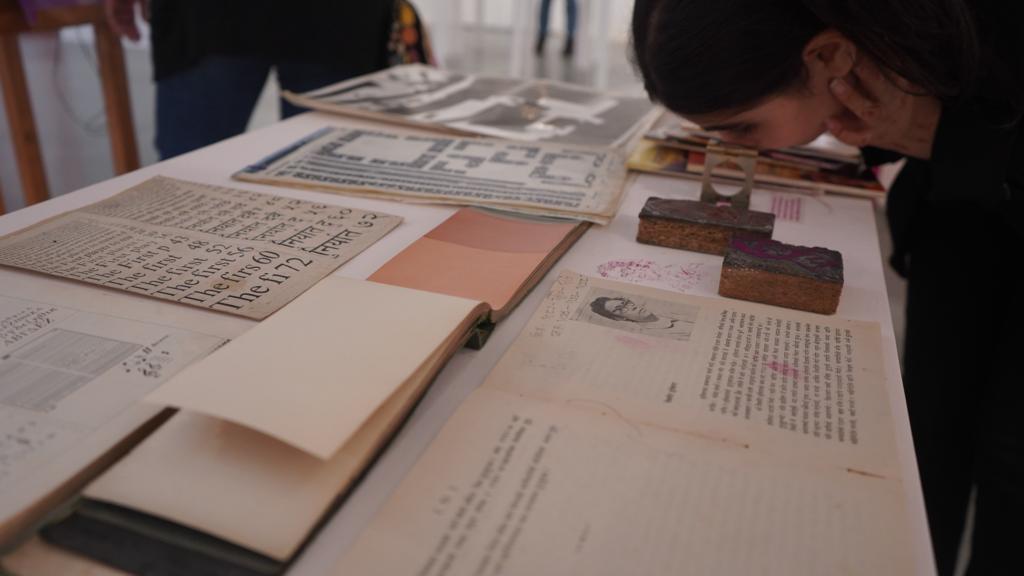

“Seeding a Grove of South Asian Solidarities” comprised of a dialogue between Karachi LaJamia, Priyankar Bahadur Chand, Zihan Karim and Thisath Thoradeniya, moderated by Anushka Rajendran. (Way of the Forest, Colomboscope, Sri Lanka, 21 January 2024. Photography: Isira Sooriyaarachchi. Copyright: Colomboscope.)

On 21 January, Colomboscope hosted a conversation titled Seeding a Grove of South Asian Solidarities, where a range of participants with distinct practices from across the region discussed this fertile ground. The panel included Karachi LaJamia, a space for institutional critique and art education outside the Pakistani university system; Priyankar Bahadur Chand’s work with Kalā Kulo, a collaborative, trans-disciplinary arts organisation in Nepal; Thisath Thoradeniya, an artist with decades of experience in a range of artist-led organisations in Sri Lanka; and Zihan Karim, who spoke about the Cheragi Art Show that prioritises the relationship between artists and publics. Anushka Rajendran, the curator of the previous iteration of Colomboscope in 2022, Language is Migrant, moderated the discussion.

Karachi LaJamia’s course Hamare Siyal Rishte, Pakistan, June 2021. (Image courtesy of Karachi LaJamia.)

Karachi LaJamia was initiated by artists and academics Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani as a reaction to the increased militarisation of Pakistan. Not only were freedoms to speak, teach and learn curtailed by the government, but Rajani and Malkani saw that their students no longer felt connected to or safe in their own city. In 2015, they built Karachi LaJamia as a space for institutional critique and art education outside the bounds of the university, allowing for deep engagement with the environment. An anti-institution, Karachi LaJamia offers long-term courses for the public that are based on collaborative learning and mutual aid. By working with the likes of the Karachi Indigenous Rights Alliance and the Pakistan FisherFolk Forum, Karachi LaJamia reclaims the right to the city by occupying and traversing through public spaces as sites of learning. Their work has taken them from land disputes, brought about by development and threats, to exploring ecologies that predate the city. Through this work, in its collaborative and deeply site-specific foundation, Rajani and Malkani not only aim to educate but also to critique, question and learn. Over the last seven years, Karachi LaJamia has built a large network of collaborators and pushed past traditional pedagogies. By engaging in art education that grows from the land they claim, the ecologies they traverse, the histories they hold, and the politics they fight, Karachi LaJamia seamlessly bridges art, academia and activism.

Exhibition view of "block prints, dot screens, and the technicolor worlds of Tek Bir Mukhiya," curated by Bishal Yonjan, Delhi, 2023. (Image courtesy of Kalā Kulo.)

Priyankar Bahadur Chand spoke of Kalā Kulo and its dedication to creating knowledge and archiving aesthetic practices in Nepal. While their work focuses on post-1950s Nepali modern and contemporary art, the methodologies employed do not necessarily conform to these temporal or stylistic boundaries. Through transdisciplinary practices, Kalā Kulo engages with the long durée, understanding that modern art does not rest in a vacuum. The breadth and fluidity of their work was highlighted through Chand’s presentation. Beginning with a brief mention of Kalā Kulo’s logistical role in bringing Nepali artists to Colombo, Chand spoke of consolidating archives for artists and providing art education that explores novel pedagogical practices away from universities. From the documentation of the work of the renowned Nepali bookcover artist Tek Bir Mukhiya to documenting tattoos, creating zines and focusing on the food that accompanies many of their events, Kalā Kulo is grounded in people, fluidity and collaboration.

Performance by Joydeb Roaja at Cheragi Art Show 6, Chittagong, Bangladesh, 2018. (Image courtesy of Zihan Karim.)

During his presentation, Zihan Karim first situated the audience in Chittagong and then moved on to discuss Jobbarer Boli Khela, a form of wrestling in Bangladesh. Dating back centuries, this traditional form usually accompanied fairs, which brought together many artisans and tradesmen selling goods from ceramics to flowers and toys. This was the inspiration behind the Cheragi Art Show by Jog Art Space. Founded in 2012 by Chittagong-based artists, Jog Art Space aims to cultivate a space for conversations between artists and audiences through a range of disciplines, mediums and practices. Thus, the Cheragi Art Show provides a forum for discourse between artists and the public without mediation or interpretation, working instead through purely collaborative curation. The sheer diversity of the audiences garnered by the Cheragi Art Show was immediately evident in Karim’s presentation, from artists and activists to children and everyday city dwellers. By breaking down the boundaries of gallery and museum spaces—which are limited in Chittagong—and taking art to the people, the freedom of the artists and the audience is mutually ensured. Though many of the founders of Jog Art Space exist in traditional academic institutions, their dedication to creating, showing and learning in everyday spaces is palpable.

Thisath Thoradeniya speaking of “The Collective.” (Way of the Forest, Colomboscope, Sri Lanka, 21 January 2024. Photography: Isira Sooriyaarachchi. Copyright: Colomboscope.)

Thisath Thoradeniya explored his journey as an artist through a range of spaces he has occupied and created to increase the availability and accessibility of art education, practice and exhibition. Beginning with his art education at the Vibhavi Academy of Fine Arts (VAFA), Thoradeniya experienced learning from established artists in opposition to art educators. Founded in 1993 by Chandraguptha Thenuwara as an independent alternative school for art education, VAFA has educated many well-known names in Sri Lanka’s contemporary art world who challenge not only pedagogy but also methodology and aesthetics. In the years following his graduation, Thoradeniya took on the role of project coordinator for the Theertha International Artists Collective. Since its inception in 2000, Theertha has continued to operate as an artist-led non-profit initiative centred around international art exchange, art education, programming, exhibitions and collaborative practice, opening its own exhibition space, the Red Dot Gallery, in 2007. Thoradeniya spoke of the difficulties of such engaged work and ultimately leaving Theertha in 2015 to make time and space for his own practice. Currently, the artist is a part of The Collective, a group of six Sri Lankan artists who came together to create collaborative multi-disciplinary exhibitions. Thoradeniya’s career, as laid out to the audience of Colomboscope, speaks to the importance of artist-led spaces and collaborative practices while simultaneously underscoring their difficulties. The precarity of the art market, the lack of support and also of diversity are everyday realities for artists in Sri Lanka.

Way of the Forest brought together not only artists but activists, practitioners, scholars and other beings of the world—down to the smallest mushroom at the Beneath the Forest Floor workshop. Through these various participants, Seeding a Grove of South Asian Solidarities spoke to pertinent questions and explorations of the festival at large—of solidarities across geographies and ecologies. Almost like branches of the same tree, the conversation highlighted just a few of the many ways in which artists, activists and educators in the subcontinent found intimate and sustainable ways of finding new ways of collaborating, creating platforms and experimenting through different festivals, archives and pedagogical models. Furthermore, in discussion with Rajendran, junctures of overlap emerged, as the panel deliberated over methods of building inclusive support structures amidst the inequitable conditions of the art market, urban development, colonial structures of art education and ecological destruction. These solidarities, whether regional or environmental, spoke to the foundational ideas that underlie the approach fostered by Way of the Forest to knowledge production, curation and dissemination: as intertwined, rooted and generative.

To learn more about the previous edition of Colomboscope, revisit Jyotsna Nambiar’s conversation with Natasha Ginwala, Arushi Vats’ conversation with Anushka Rajendran, Annalisa Mansukhani’s conversation with Omer Wasim and Thisath Thoradeniya and Ankan Kazi’s reflection on the radio programme A Thousand Channels.