Expanding the Field: Curators' Roundtable

As part of a series of talks curated by Priya Chauhan hosted at the fifteenth India Art Fair 2024, Curators’ Roundtable: Criticality in the Contemporary saw the coming together of curators from across a range of institutions and diverse approaches to practice. The discussion featured Vidya Shivadas, Director of the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art (FICA); Neeraja Poddar, the Ira Brind and Stacey Spector Associate Curator of South Asian Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; Rattanamol Singh Johal, Assistant Director, International Program at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA); Sabih Ahmed, Associate Director and Curator of the Ishara Art Foundation; and Anushka Rajendran, Curator of Prameya Art Foundation. The panel was moderated by Arnika Ahldag, Head of Exhibitions at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru.

.png)

Curators’ Roundtable: Criticality in the Contemporary at the India Art Fair (New Delhi, 3 February 2024. Image courtesy of India Art Fair.)

Ahldag started the discussion by asking the panellists to introduce their practice and speak about how the role of the curator has changed in the present. The positionality of the curators as working with and within institutions framed their answers. For Poddar, who works in America, the need to engage with audiences becomes an important aspect of the curatorial process. In agreement, Rajendran highlighted the creation of communities and the fact that, as curators, they think of their practice in an expanded sense by providing and creating support structures for artists. Commenting on the shifting role of the curator, Rajendran argued that while their role continues to be one of care and that of maintaining the artists’ conceptual and material integrity, it has expanded into more discursive modes of doing so. Shivadas spoke about the manner in which the curatorial and the exhibitionary have moved away from static forms to more dynamic forms, where relationality, dialogues and coproductions allow for more creative ways of engaging with curatorial practice. Speaking with reference to his work at MoMA, Johal highlighted the possibilities for conversations across space and time between artists that have not been well represented in narratives of history, by creating context and connections through research-driven practice. Ahmed traced the etymology of the term “curation” to care, and how that raised questions about the role of the curator in the post-Covid era, where so many layoffs led to a certain disillusionment about what the nature of this “care” was. He stated that perhaps a new conversation around such concepts needed to be framed that allowed for the curatorial to be dissociated from the museological. Complicating this relationship by drawing attention to the closeness of the museological with the mercantile (visible in the increasing privatisation of museums and their participation in art markets), Ahmed’s provocation was to think of the radical possibilities of curatorial practice. He argued for the need to address the transformative potential of the curatorial through attempts at deterritorialising and re-territorialising subjects, objects and knowledge.

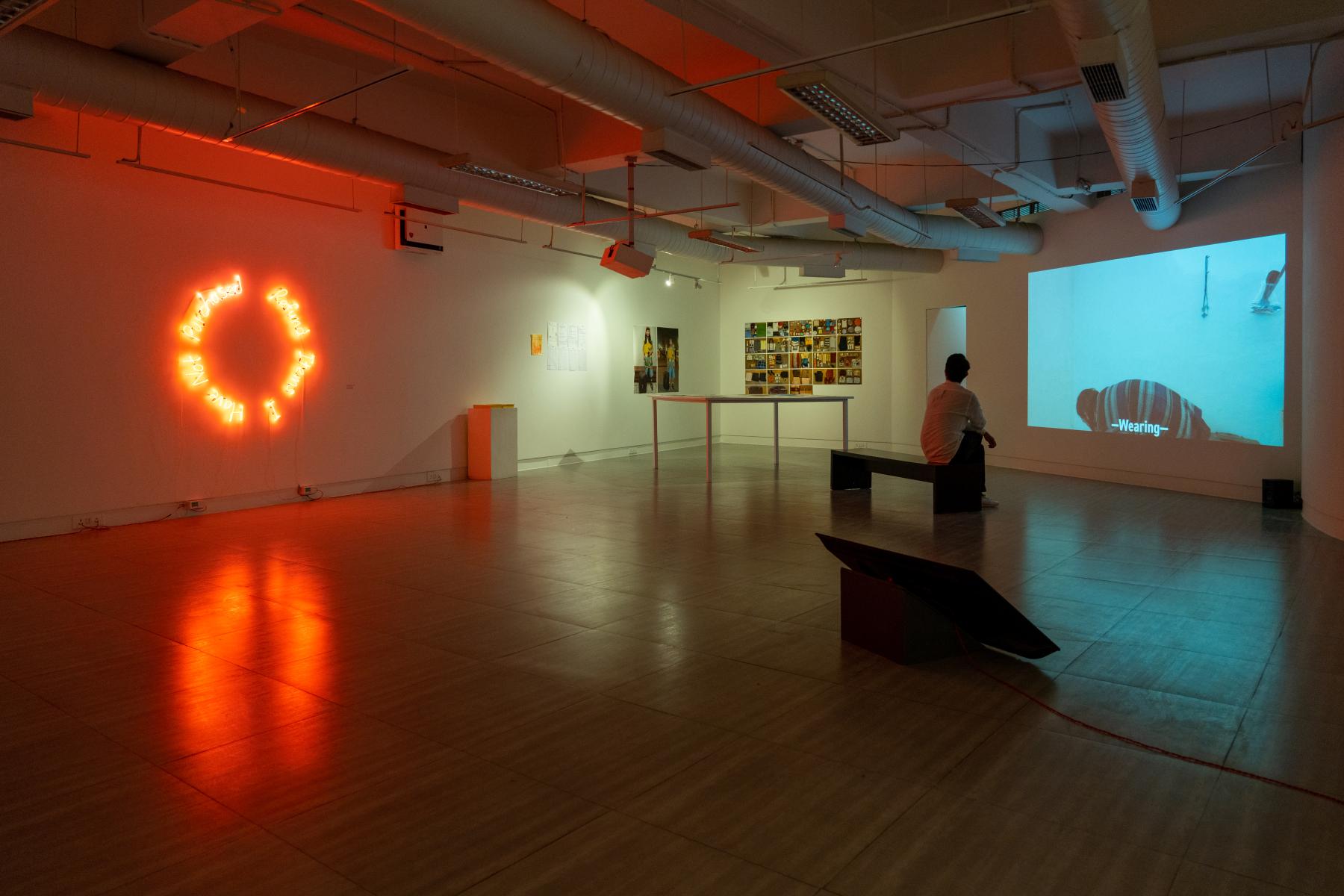

Exhibition view, Yoshinori Niwa: Rehabilitating our human spirit under capitalism, at the Japan Foundation in New Delhi, presented by Prameya Art Foundation, 2023. (Image courtesy of Prameya Art Foundation.)

The panel was then asked to respond to the notion of South Asia as they dealt with it in their practice. Rajendran spoke about moderating a panel at the 2024 edition of Colomboscope on forms of solidarity, where overlapping histories and modes of working allowed participants to share and learn from each other. She pointed out that South Asia could also be thought of as a way of working against various infrastructural odds by thinking beyond the literal borders of nations to arrive at a regional state of mind. Since FICA primarily works with artists from India, Shivadas spoke about the idea of the region and the necessity to consider diversity within as well, referring to their recent grant for Himalayan practitioners. She also emphasised the mutual process of exchange with artists, which informed her experience as a curator. FICA has sought to maintain and sustain relationships with artists by offering a space of care and nurturing in Delhi. The space of the exhibition, for Shivadas, then offers itself as a charged site, with an assemblage of energies and creative forces that disperse through the bodies that visit the site. For Johal, South Asia as a conceptual category offers an important vantage point to approach and think through transnational research. Johal agreed with Ahmed’s point about the need to maintain sensibility around the radical aesthetic and political aspects of practice, while taking into account its complex terrains. He spoke of the way in which connections could be made between artists like Mrinalini Mukherjee and Ana Mendieta through their figurations, or Amar Kanwar’s The Torn First Pages, which spoke to Paris-based Turkish artist Nil Yalter’s work in their exploration of politics and video on view as part of Signals: How Video Transformed the World (2023). Thus, dialogue is possible between things that may not necessarily be directly connected in an art historical narrative that is regional or geographically-specific.

Dealing with historical collections, Poddar highlighted the challenges of maintaining the unique character of South Asia within contemporary transnational dialogues. Given that forms of organisation within the museum are chronological and region-specific, the curatorial intervention is in the form of display, where the focus then becomes on themes that everyone can relate to. Poddar spoke about working with the New York-based Pakistani artist Shahzia Sikander, who was invited to create a video installation as a contemporary interpretation of a seventeenth-century manuscript from their collection, the Gulshan-i-Ishq. She also spoke about the exhibition Encounters in Exile, which she worked on as a response to the pandemic. Drawing on the theme of exile in the Ramayana, the exhibition became a way of activating the historical objects in the collection through the contemporary moment. Ahmed referenced the concept of “complex geographies” to foreground the fact that South Asia is not a geographic region but a historic formulation. In this way, the term is viewed differently from different locations. In order to complicate this framing, the approach at the Ishara Art Foundation has been to invite artists to curate and share their perspectives as well as bring others into this conversation. Ahmed also argued that he noted an increasing trend where the contours of South Asia are beginning to be framed through xenophobia.

Installation view of Sheher, Prakriti, Devi, curated by Gauri Gill at Ishara Art Foundation, 2024. (Image courtesy of the artists and Ishara Art Foundation. Photography by Augustine Peredes/Seeing Things.)

Ahldag also posed a question about the future of curatorial practice. Ahmed responded by stating that the terms and impulses behind what curators do need to be reassessed. He believes that the exhibition as a space for discussions or contemplation can also become a place for testing the ways that things have historically been assembled, thereby enabling attempts at undoing these. For him, the exhibition of the twenty-first century seeks to dissociate the exhibitionary complex from exhibition making. Poddar added that in her practice, she always tries to return to the questions “Why does what I do matter?” and “How do I make what I do matter?” Shivadas was optimistic about the open-ended forms that exhibitions can take. She stated the example of an online reading group with artists working on agrarian practices, that was developed into a reading room featuring images from their WhatsApp conversations and engagements throughout the year. This form also allowed others to participate in the conversation, generating many productive possibilities. Ahldag mentioned that these creative configurations coexist with everyday challenges of censorship, the curator’s self-censorship and negotiating between the demands of institutions.

Extending the question of censorship, an audience member asked about strategies that the curators used to work around it. Rajendran spoke about arriving at the realisation that her primary concern as a curator is to sustain critical conversations in ways that are safe for artists by using various subversive strategies. She brought back the question of the audience as a contingent community, where the exhibition model could be thought of as something incidental to the formation of such meaningful communities. Such communities can exist before and persist beyond the exhibition itself. Johal added that one such historical strategy was to resist the instrumentalisation of art by highlighting the complex ways of reading the works. Ahmed argued that such strategies or approaches to censorship may vary from context to context. However, curators could also try to find ways of saying things without necessarily saying them, or resist the trap of liberal declarative politics and also declare their politics when necessary.

Exhibition view of With great ease: The photography of T.S. Satyan, MAP, Bengaluru. (Image courtesy of Philippe Calia and MAP.)

Inextricably linked to politics, the panel offered compelling insights into the discourse around curatorial practices in the present, giving a sense of how the participants have personally mediated and navigated everyday challenges over the course of their careers. It was interesting to note the manner in which they overlapped as much as the way in which they differed in their opinions. As the conversation moved across space and time, it served as a reminder that criticality in the contemporary is dependent on the possibilities and co-existence of multiple viewpoints simultaneously. The curator thus operates as a mediator, straddling the institutional while also affecting change from within established networks. Some of the issues and questions raised by the panel extend and can be applied to thinking not just about art but also about engagements with all forms of expression and everyday experience. To approach critical thought requires the possibility of forums to discuss, debate and disagree in order to combat stagnation around ideas. As the panel wrapped up by addressing a question about the importance of pedagogy as linked to curatorial practice, Ahmed spoke about the manner in which there is a great transformation underway as solidarities between students, teachers and practitioners are emerging. He concluded by emphasising that the focus should not be on the future generation(s) but on the future of ideas.

.png)

Curators’ Roundtable: Criticality in the Contemporary at the India Art Fair (New Delhi, 3 February 2024. Image courtesy of the India Art Fair.)

To learn more about programming and parallel shows associated with the India Art Fair, read Shankar Tripathi’s review of Zahra Yazdani’s show Scripted Selves: Sutures of Signs and Symbols at Latitude 28. To learn more about curatorial and academic perspectives on/within South Asia, read Mallika Visvanathan’s piece on the colloquium Imaging South Asia and watch a discussion around How Secular is Art? On the Politics of Art, History and Religion in South Asia (Cambridge University Press, 2023), edited by Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Vazira Zamindar.