Daule Daule: Through the Tharu Lens

“Daule Daule/डउले डउले” in the Chitwaniya Tharu language is a form of greeting that translates into “How are you doing?” There are many different variations of this greeting across Tharu communities. In East Nepal, the Tharus use “Gor lagaichhiyai /गोर लागैचियै” and in the West, the greeting is “Ram Ram/राम राम” or “Jaya Gurbaba/जय गुरबाबा.”

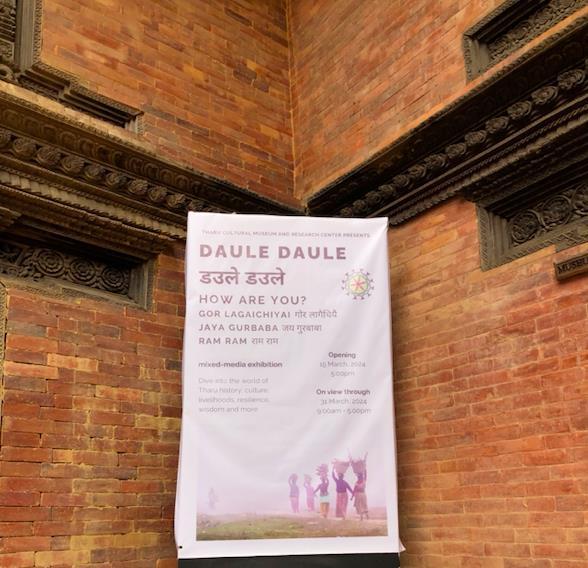

Entrance to the exhibition at the Patan Museum. (Image courtesy of the author.)

How are you doing? can be a complex question—it is a simple greeting and can also be an invitation to go beyond. The Daule Daule exhibition, as the phrase suggests, gives the viewer a glimpse into the lives of the Tharu community of Nepal. It shows us moments from their everyday lives and also dives into their rich repository of indigenous knowledge. Curated by Birendra Mahato, Indu Tharu, Sanjib Chaudhary, Lavkant Chaudhary, Arnab Chaudhary, Maria Bossert and Tom Robertson, the exhibition documented the fishing, agriculture, pottery, culinary and tattooing practices, as well as the religion, art and politics of the community. Supported by the Tharus and Friends Association USA and Fulbright Nepal, Daule Daule was on view at the Patan Museum in Lalitpur from 15 to 31 March 2024.

Tharu women fishing in the river with “Helka” and “Diliya.” (Judith Chase, 1972. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Daule Daule attempted to tell Tharu stories through their own lenses—a perspective that the curatorial team found lacking in previous exhibitions featuring the work or lives of the community. Out of the seven curators that worked on the exhibition, five belong to the Tharu community from different parts of Nepal. Tom Robertson, who has been studying Tharu history since 2007, writes, “The Tharu make up 6.2% of Nepal’s population (as per the 2021 census). One in every twenty Nepalis is a Tharu. They outnumber the Gurung, Limbu and Newa peoples. And yet, most Nepalis often know very little about Tharu culture and history.” The exhibition displayed photographic documentation of the lives and culture of the Tharu community, from archival photographs to more recent images, as well as a video exhibit and a few everyday items like the fishing nets on display.

Tharu women carrying firewood from the forest for the Magh festival. (Vivek Chaudhary, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.)

The first image that one encounters in the exhibition is of a group of women taking firewood home, photographed by Vivek Chaudhary in 2016. Similar images of women of various ages carrying firewood, grass and pottery are present throughout the exhibition. Women and their often invisible roles in the home have been the backbone of the Tharu community’s survival. The selected documented images bring them and their labour to the forefront through visual stories about their lives, struggles and resilience.

Indu Tharu played a special role in curating the photographs related to women from the community. In the curatorial note, she writes, “I don’t see Tharu women as free but as persistent. When an outsider sees Tharu women working in the fields or going fishing, s/he might assume they are free because they are going outside of the house. But the reality is that this is the women’s struggle for their lives.” The most colourful section in the exhibition depicts a time in 2015 when the Tharu women, all clad in their vibrant traditional clothes, became a symbol for the Tharuhat Tharuwan Movement—a political movement about the rights of an indigenous community that came as a response to the constitution of the country.

A woman showing her “Godna,” a traditional Tharu tattoo on her hand. (Maria Bossert, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.)

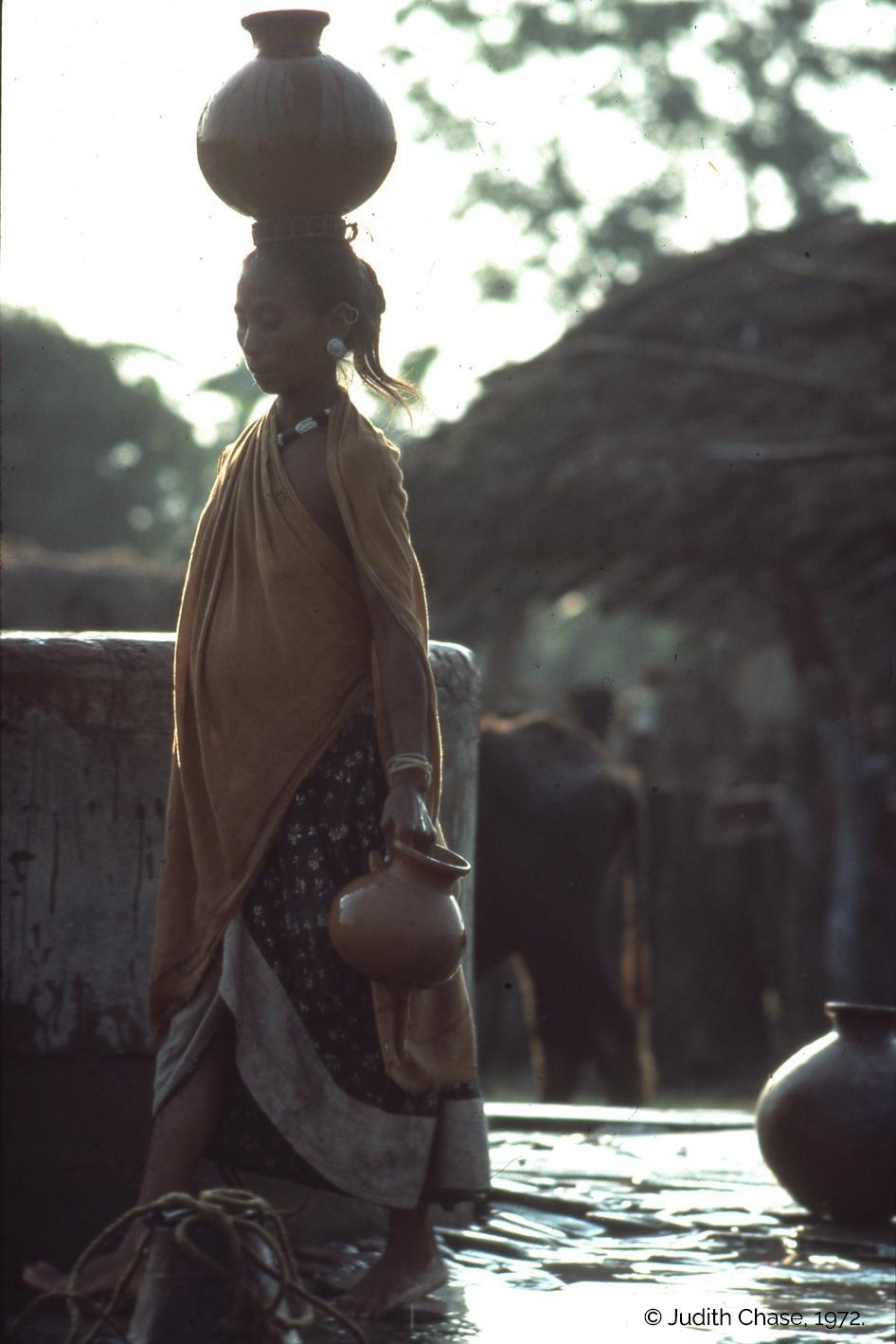

The photographs for the exhibition were sourced from individual photographers—some of whom belong to the Tharu community—and from archives and collections like the Doug Hall Peace Corps Collection. The images on display showed a range of activities along with highlighting the importance of environment and ecology for the community. Some pictures were about the serene beauty of the nature that Tharus live in, while others showed the Tharu people weaving traditional baskets and bags. A photo by Judith Chase from 1972 portrays Tharu deities made from wood placed in village shrines.

The exhibition design also framed these images alongside fishing nets and equipment, highlighting the importance of the practice within Tharu culture. This is also related to the complications around fishing today, as the community is not allowed to fish inside or even access the national park. The practice, however, still sustains a majority of the Tharus. Fishing is also a community activity, and thus Tharus rarely go fishing alone.

Fishing nets and woven baskets used by the community, on display in the museum. (Image courtesy of the author.)

A poignant and pressing question Daule Daule asks is—how can we save the traditional and indigenous knowledge available in the community in these times of rapid industrialisation and globalisation? As with fishing, clay pots are an integral part of the community, but the making and use of such pots is now diminishing. Likewise, the weaving skills of the community that produced the dhakiya, nuiya, bhauka, among others, are also on the verge of extinction. The exhibition reflected on the slow erosion of indigenous ecologies by noting, “Nowadays, plastic materials have taken over. Tharu villages are now filled with plastic bags, plastic ropes, plastic buckets and plastic water bottles.”

The curatorial team believes that the main aim of Daule Daule was to show that Tharus can tell their stories from their own perspective. The sole ownership of this exhibition lies with the community. They believe that the direct involvement of the community and its members, which has often been missed in the past, is a differentiating factor for this exhibition and forms its cornerstone.

Tharu women carrying water in “Gagri” i.e. terracotta pot and “Karuwa” from a water well. (Judith Chase, 1972. Image courtesy of the artist.)

To learn more about the Tharu community, revisit Anisha Baid’s essay and curated album on Nepal Picture Library’s The Skin of Chitwan.