Metonym, Anthropocene: Our Conspiring Hosts

Our Conspiring Hosts, a group show curated by Adwait Singh for Anant Art at Bikaner House, ran from 28th March to 8th April 2024. Telescoping across jamnapaar Delhi, Amazonian floods, villages dotting the coast of Odisha, oil fields in Assam, alluvial mounds in Kashmir, coastal Colombo and a National Park in Nepal, the exhibition assembled a geography of disaster, dispossession, and damage, ravaged by the oft-cited watchword of our age: the Anthropocene.

The curatorial note establishes three “metonyms” which group the works displayed into ecological units: rivers, vines, and microbes. While organised conceptually, there were no spatial enclosures binding the works of each category together. They are instead spread diffusely around the gallery, with works of one category in proximity and conversation with another. It is a carefully choreographed microcosm, where one swims through a sprawling biome of forms to encounter an attentive reinvention of South Asian ecologies.

Imaad Majeed, The Impossibility of Leaving / The Possibility of Coming Out, 2022.

We are confronted by the long-cast shadow of colonial interventions in Karan Shrestha’s Mikania micrantha (2021), known popularly in Nepal as banmara—the killer of forests. Native to Central and South America, this invasive weed was discovered in Nepali forest tracts in the 1990s and has emerged as a vexing threat to the ecological system. Its outgrowth eats away plants fit for animal consumption, endangering not only its cohabiting plant life but also animals who depend on forest vegetation as well as pastoral communities that draw on the resources of the forest, such as firewood and fodder. Shrestha’s tableau brings banmara to the show by inscribing it as a botanical drawing in monochrome, a looped video of an insect dying amidst this weed, and a small parcel of tortured landscape with a barbed wire cutting through.

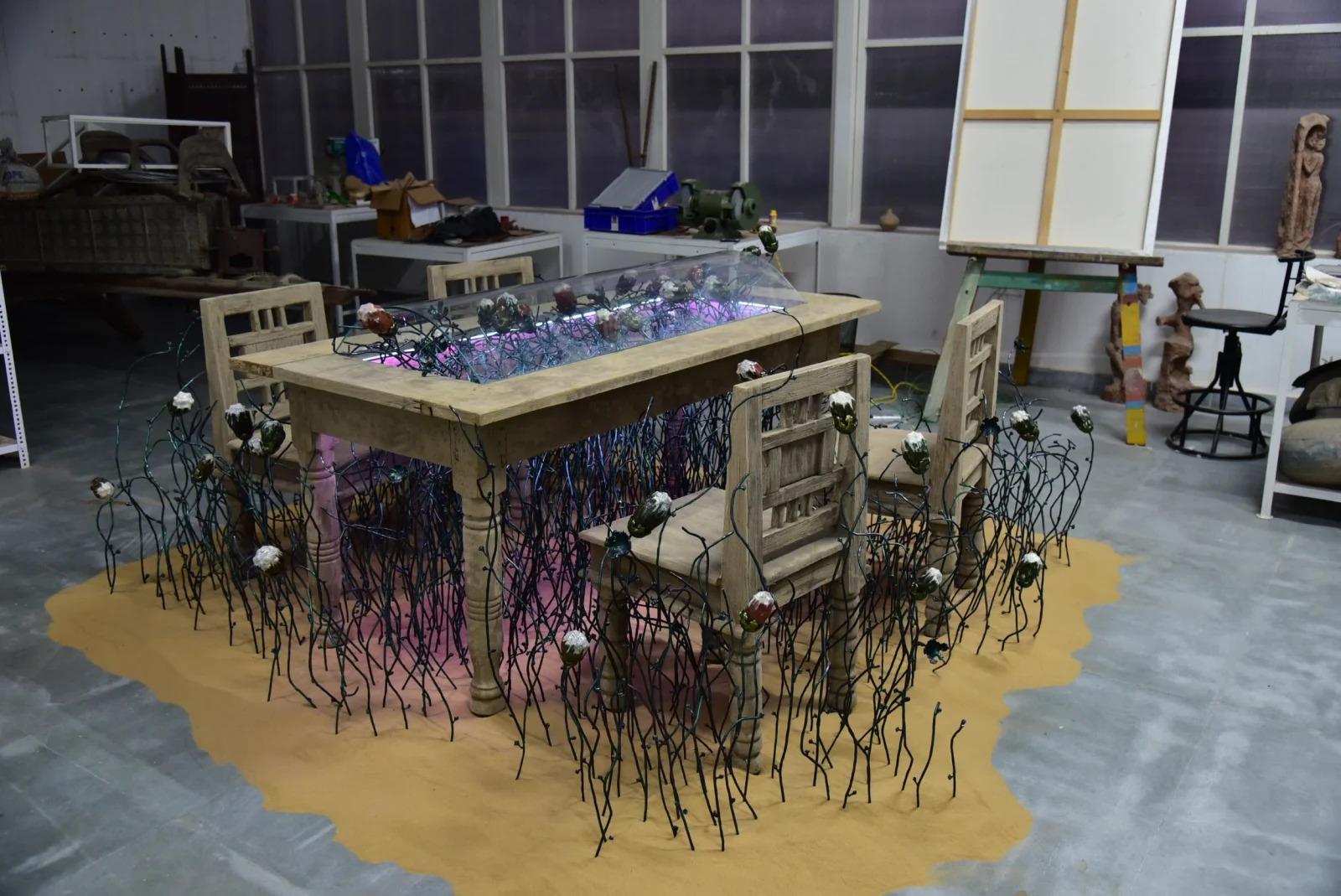

Bhimanshu Pandel, घर आंगण गुवाड मे खेतां री ही गूंज, 2023.

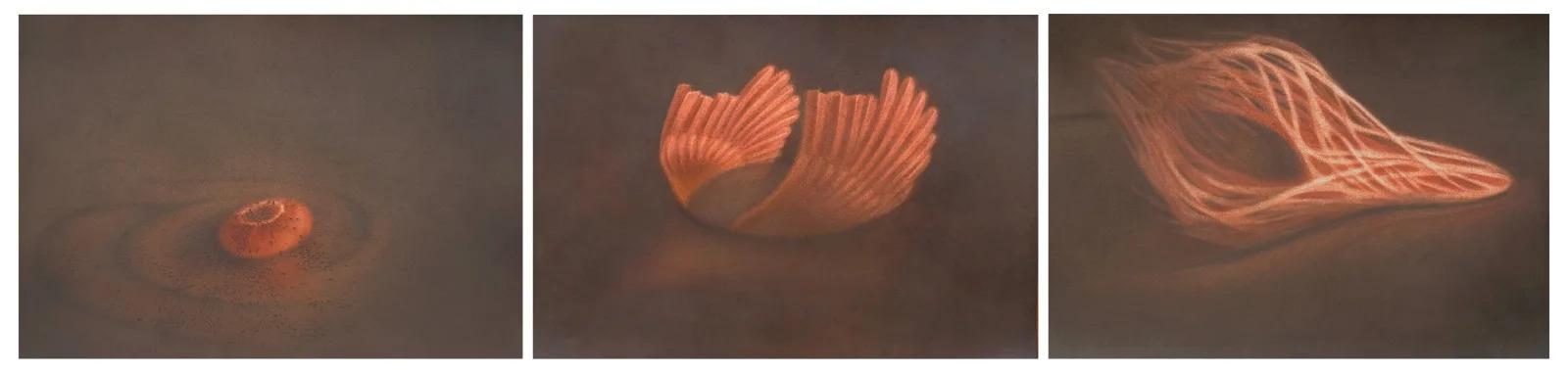

Garima Gupta’s Morning After Flood (2024), less literal, is a suite of three colour pastel and pencil drawings cast in burnished auburn. They serve in equal parts as a sketching exercise, a mnemonic device, an object lesson, and a diary. Shot through her memories of the annually flooding Yamuna river in the low-lying jamnapaar area and her more recent experience of the rising waters in the Amazon rainforest, these drawings dramatise minor mementoes of resilience—a colony of ants feeding from a lone fruit, a macaw with clipped feathers and a fig tree, dead and decomposing. Bhimanshu Pandel’s installation घर आंगण गुवाड मे खेतां री ही गूंज (2023) and Temsuyanger Longkumer’s sculpture Refuge I (2019) summon phantasmagoric scenes of multi-ecological entanglements. The former appears as an impossible dining table teeming with a metallic bush of flowering shrubs, while the latter is presented as a terracotta vessel recalling prehistoric pottery with a tangle of earthworm-like creatures snaking in its innards.

Garima Gupta, Morning After the Flood, 2024.

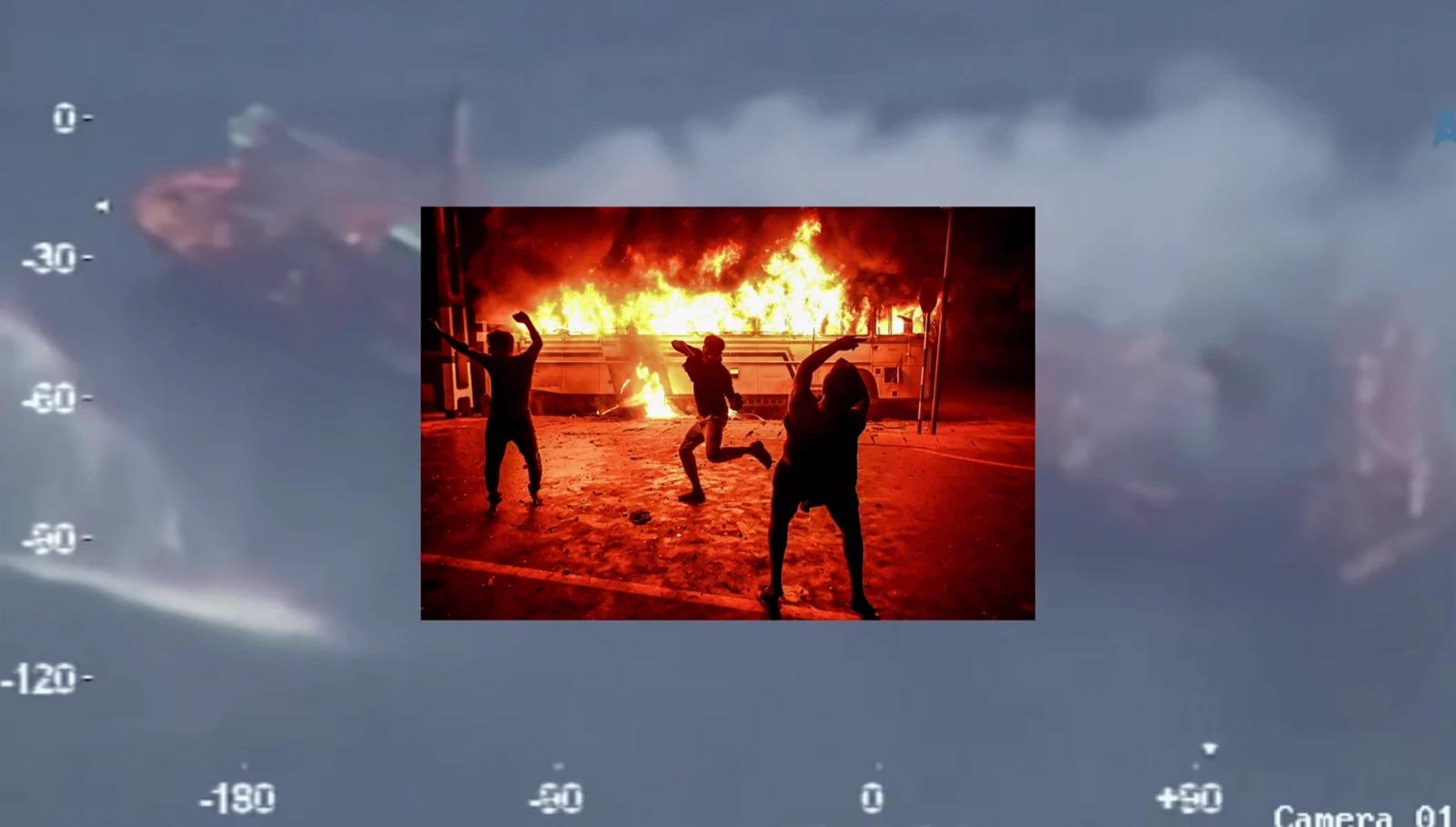

In their curatorial note, Singh underlines the gravity of human interventions—which can collapse the variations between colonial, postcolonial, and neoliberal. This theatre of anthropocentric excesses and extraction is in fact a scene of crime, one that is resolutely committed towards those at the margins of our ecosystems, human and non-human. Normalisation of a Disaster (Baghjan, Assam) (2020) by Devadeep Gupta takes us to one such scene. Shot in the aftermath of what is now known as the Baghjan Oil Blowout, Gupta captures the dazed stillness around the oil field, which remained on fire for six months. We see idyllic Assamese backwaters, swirling mists of clouds, groups of people sitting, walking, gaping—one could almost miss the tall wick of fire, burning away at a distance. Absorbed in the “circadian” rhythms of everyday life, the spectacle of this fire simply dissipated—and it is in this response that we find an occasion for horror almost at par with the event itself.

, 2020.jpg)

Devadeep Gupta, Normalisation of a Disaster (Baghjan, Assam), 2020.

Paribartana Mohanty’s video Ocean Mud Pickle (2023), steers one through a history of the cyclone-riddled Odisha coastline. A speculative excursion through archives, cartographic charts, memories, interviews, and the folk tradition of Daskathiya, the video jostles with the unknowable future of the village of Satabhaya, which has been submerged by the Bay of Bengal. An accompanying series of lenticular prints brings in the spectre of the village—as one’s gaze moves, we see beaches with people, cattle and homes receding into barren terrain. In his apocalyptic inscriptions of reality enjoined by mythic futurology, Mohanty grafts a meditation on the landscape with one on the region’s rural lifeworld.

Paribartana Mohanty, Bike Man, 2022.

Salman Bashir Baba introduces another landscape, more arid and gravely contested. In Spectral Land (2023-24), Baba stages photographs of a mendicant-nomad, an almost prophet-like protagonist, atop mounds of alluvial deposits. Residue of ancient riverine activity, these mounds, known locally as karewas, are an outpost of Srinagar, Kashmir. Looking out into the vastness of a city beyond the frame, Baba inverts conventional expectations of Kashmir’s arcadian beauty, trailing a distance from bare life to bare land.

Salman Bashir Baba, Spectral Land, 2023.

As an exploration of the turning tides of the Anthropocene, Our Conspiring Hosts played host to a cast of works that perceptively interrogated the heart of its defining condition—the human onslaught. More serendipitously, it presented a constellation of practices that, in considering ecology alongside regional history and geography, leave us with a topical survey across provinces of South Asia that have only recently begun receiving attention.

To read more about practices that think through the Anthropocene, see Anisha Baid’s essay on The Skin of Chitwan (2020), Sukanya Deb’s essay on Paribartana Mohanty’s Four Songs of Apocalypse (2021) and Annalisa Mansukhani’s interview with Ravi Agarwal on his co-curated exhibition Time as a Mother (2023).

All images courtesy of the artists and Anant Art.