Modern Architectures of the Kathmandu Valley: A Brief Overview

The architecture of the Kathmandu Valley is primarily identified with the three Durbar Squares. These iconic structures were built during the rule of the medieval Malla dynasty in Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur—the three cities that jointly form the valley. The region is also synonymous with other historic built structures such as the Rana Durbars and palaces spread across the valley, which were constructed by the Rana dynasty during their 104 years of rule from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s. Very often, the popular image of architectural spaces in Kathmandu shifts from these medieval and early modern structures to the haphazard urbanisation that has taken over the valley in the last few decades.

Visitors to the exhibition (Image courtesy of the Kathmandu Institute).

There seems to be a time lag between the architectural making of the city. What happened following the Rana rule and before the present time? Were there no architectural developments taking place? An attempt to examine the architectural histories and answer such questions comes in the form of the exhibition Modern Encounters in Architecture Kathmandu Valley (1945–1985). Hosted by the Kathmandu Institute at the Taragaon Next, a museum and cultural space in Boudha, the exhibition ran from 22 March to 18 April 2024.

The project attempts to document early modern buildings from 1945 to 1985 that are considered landmark structures built outside of the largely historic “heritage” core areas. The exhibition consisted of flex boards that displayed photographs of the buildings, drawings, site plans, floor plans, archival photographs and a brief bio-note about the architects who designed them. The exhibition accompanied the publication of a book, Modern Encounters in Architecture: Kathmandu Valley 1945–1985 (2024), edited by Biresh Shah, Jharna Joshi and Poonam Shah and published by RICH Publishers.

Family Planning Centre, 1970 (Image courtesy of University of Pennsylvania Archives).

The venue itself is tied into the themes of the exhibition, as Taragaon Next is housed in a modernist barrel-vaulted red-brick and glass structure. It was designed by the Austrian architect and planner Carl Pruscha in the 1970s as the Taragaon Hostel, meant to provide lodging for long-stay foreigners in the valley. The site was later restored and began functioning as a museum in 2009, now housing archives from the Nepal Architectural Association (NAA). It is therefore fitting that an exhibition exploring documentation of the oft-overlooked “modernist” structures from the mid-twentieth century is displayed in one of the buildings it seeks to highlight.

A good number of these structures can be found concentrated around the current core area of Kathmandu—starting from around Tripureshwor and leading to the Narayanhiti Palace Museum and surroundings. Pointing out the differences in the modern architecture of the valley, the editors of the book state in its introduction, titled “Documentation Challenges of Early Modern Buildings in Nepal”:

The traditional “heritage” structures have distinct features that are recognized as unique to Nepal, such as the use of specific local bricks, highly carved wooden elements and pitched roofs with wide overhangs. When Nepal opened to the outside world and modernization in the 1950s, new materials and technologies were introduced, such as concrete and prefabricated structural elements.”

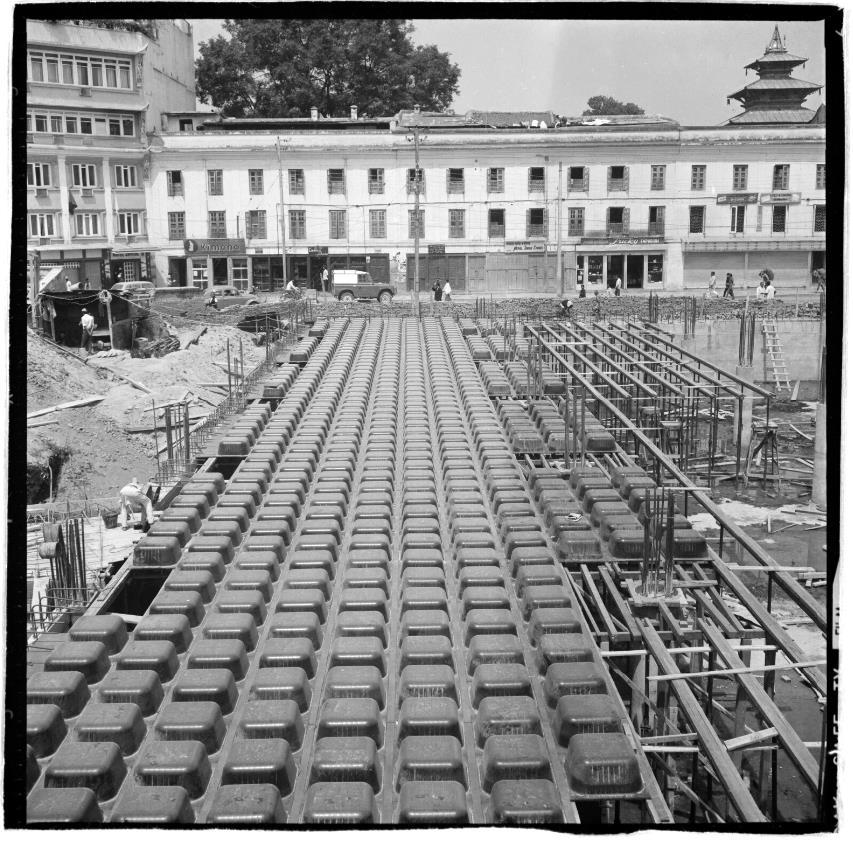

Bishal Bazaar (Image courtesy of the Dirgha Man and Ganesh Man Chitrakar Art Foundation).

Many of these buildings are the first of their kind. For instance, Bishal Bazaar was the first supermarket building in the country and the first important public-private partnership project. Other structures highlighted in the exhibition included the Dasharath Rangashala, which was the first sports stadium in Nepal and the Soaltee Hotel, which was the first modern luxury hotel built in the International Style of architecture. Others like the TU Central Library, Nepal Academy, Rastriya Sabha Griha and the Tribhuvan International Airport Terminal form a central part of our everyday lives.

Tourists and visitors to Kathmandu have likely seen at least a few of these buildings. However, for the general public, a conscious realisation that these buildings are part of the larger architectural history of the city is still lacking. The Ghantaghar, Durbar High School and Trichandra College represent the early, pre-1934 “modern” buildings in the city and are perhaps among the few that come to mind when we think of architecture from the recent past. But much of the modern architecture in the valley lies in the shadow of the past and is often ignored or forgotten.

Royal Nepal Academy, now Nepal Academy (Photograph by Shankar Nath Rimal, courtesy of the artist).

According to the Ancient Monument Preservation Act (1956), for any building to be classified as "heritage" in Nepal and be protected in its original form, it must be at least a hundred years old. Laws to protect contemporary buildings are frail and ineffective, as seen in the case of the Family Planning Centre building. The centre was commissioned to be designed by Louis Kahn in 1970. Later on, the building was converted into the offices of the Ministry of Health. In 1995, the Ministry made alterations to the original design by adding metal roofs over the terraces to create more floor space. The local architectural community retaliated by staging demonstrations and launching a media campaign. The Society of Nepalese Architects even filed a legal case in the apex court. But the original design could not be saved.

Walking through the exhibition, one cannot help but wonder if Kathmandu, which has now become an unmanaged urban sprawl and where a piece of land costs a lifetime of savings, can still salvage its more recent architectural history and give it as much space as its older heritage. Exhibitions and projects like these are necessary to initiate a dialogue around collective memory and the understanding of these architectural structures as well as the role they play in shaping the valley’s history.

Soaltee Hotel (Photograph by Alan Fairbank, courtesy of the artist).

To learn more about ways of approaching architectural histories, revisit Arushi Vats’ essay on Chirodeep Chaudhuri’s photographic series Seeing Time: The Public Clocks of Bombay (1986–ongoing), Sukanya Baskar’s essays on architect Jeet Malhotra’s photographs and the Modernist aesthetic in architecture and Annalisa Mansukhani’s review of Clara Kroft Isono’s Bawa’s Garden (2022), which explores the life and work of the Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa.