Creating the Imageograph: Nina Sugati SR and the Counter-Cultural Image

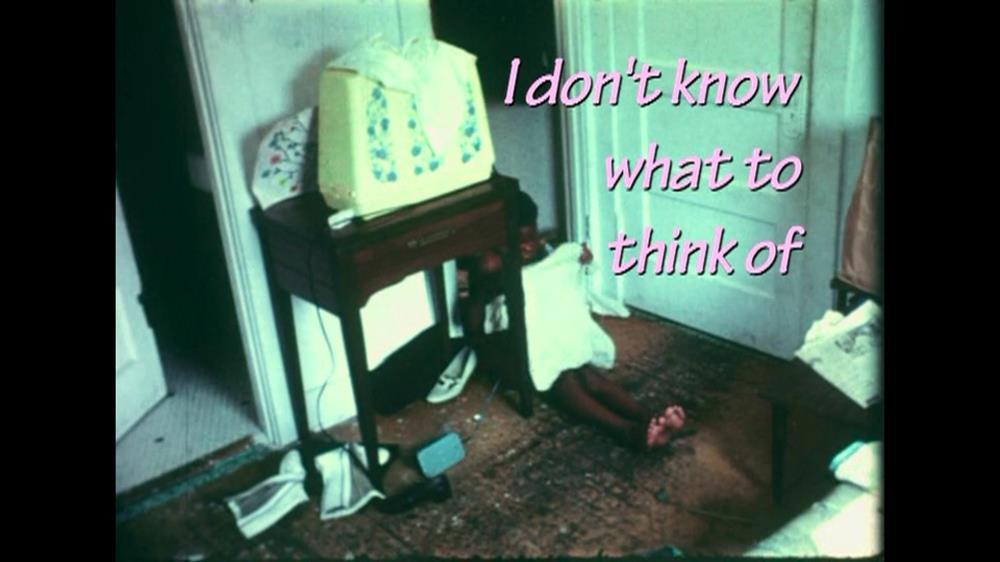

Rovshen’s films constantly use stylised text on the screen to foreground the speech of her characters and communicate its affective tone. Still from Breaking Ground (1972).

The Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW), organised by Akbar Padamsee in Bombay between 1969 and 1972, brought together artists across disciplines to create a space for collaboration and experimentation. Nalini Malani, Gieve Patel, Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, and many others participated, and VIEW is credited with being one of the few spaces to create media art at the time. An Exploded View, conceived and moderated by Nancy Adajania at the Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation (JNAF) in 2021, showcased experimental films that were produced out of the artists’ encounters and dialogues at the landmark workshop. It forms, as Adajania put it in her curatorial essay, “a key node in the long arc of Indian new media art.” Perhaps most importantly, the exhibition made these celebrated experiments available to a general audience online. As part of this workshop, several filmmakers, photographers, printmakers, animators and a psychoanalyst were brought together to find new ways of conceiving images for a politically informed, experimental avant-garde visual language. These included Padamsee himself, who made the fascinating stop-motion film Syzygy (1970), channelling abstract mathematical thinking and anti-representational provocations in counter-cultural music, like the work of John Cage.

Still from Breaking Ground (1972).

For an artist like Nina Sugati SR (aka Nina Shivdasani Rovshen), these dialogues led to the conception of the “Imageograph,” which was a compound of the moving image invested with photography’s access to the human spirit. The concept was realised through technical innovation, but it was animated by the filmmaker’s visual relationship with herself. As Rovshen mentions in a conversation with Shai Heredia in 2005, “The first photograph I took of myself when I was 12 years old was an Imageograph of what I thought was my spirit. I did not know or understand what I had done.” Eluding the language of rational, conscious categories, the Imageograph works as a lead or a subterranean passage into the “political subconscious” of a historical period marked by cross-cultural dialogues in political struggles and expanding consciousness through the counter-culture’s experiments with sensibility. Marking her motivation to make films from an extra-literary perspective that privileges the visual, unlike the literary films of a realist filmmaker like Satyajit Ray, Rovshen says,

“To communicate words maybe (sic) very good, but to expand somebody’s imagination and to make people see something that you see and you want them to see, some vision of yours that you want to share, only a visual can do that. Visuals are limitless and when I realised the conceptual significance of a visual, that I think was the seed of Imageography.”

The Imageograph helped her to yoke a conceptual category to a technologically defined practice for representing the abstract operations of the subconscious mind. This conceptual movement helped Rovshen create some of her remarkable experimental short films before making her acclaimed film, Chhatrabhang (1976).

Stills from Breaking Ground (1972).

The exhibition featured Rovshen’s shorts Breaking Ground (1972), Hope No One’s Listening (1973), and World of All Intelligence (1973), all films made a few years before she moved back to India to film Chhatrabhang. Rovshen made them after picking up an Éclair NPR 16mm camera at CalArts, where she was an MFA student. Even though these shorts are set in a blighted American landscape, reflecting its various social dysfunctionalities, her mode of constructing the spectral authorial gaze “began in India.” It is a testament to the evolving, experimental vocabulary of both film and political struggle—inseparable for Rovshen at the time—when decolonial ideas were freely exchanged across geographical spaces, from Vietnam to America via India, in this case. Scholars like Aijaz Ahmad have termed the years between 1945 and 1975 “the high period of de-colonization” in an attempt to expand the artistic contexts of newly emergent states beyond their realist-nationalist themes towards a more complicated, experimental form like those being developed in the new third cinemas of Latin America. It was part of the agenda followed by films like Syzygy too.

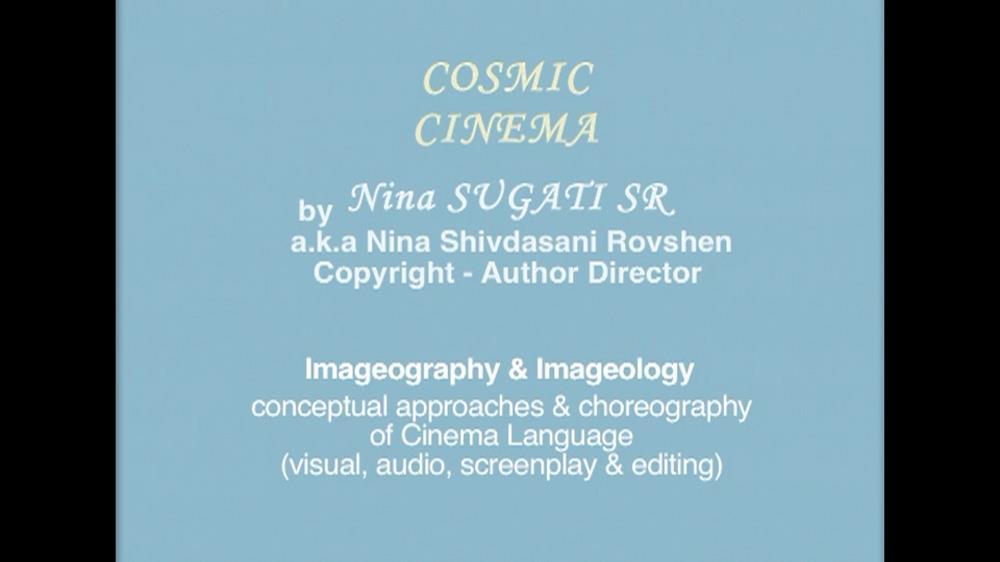

The end credits display the use of "Imageography" and "Imageology" as concepts of cinematic visual language in Rovshen’s films.

Thus, thinking about the structural inequalities of marginalised, repressed subjectivities in one culture, manifesting as racism or anti-Semitism in America, led her to explore Dalit realities in north India in Chhatrabhang. Rovshen's aesthetic vision can be placed in a direct continuum with her cosmopolitan sense of anti-authoritarian politics. It is worth noting too that the political context of works like Chhatrabhang (as well as her early shorts) was also brought about by the Dalit Panthers, an outfit that was popular at the time and clearly inspired by their radical counterparts in America, the Black Panthers.

Still from Hope No One’s Listening (1973).

As anti-racist histories and narratives of Dalit struggle get erased within our normative, mainstream media landscapes, Rovshen’s films evoke the complex intersections of political struggle that have informed the global movement for rights and recognition and are essential to recovering these alternative frameworks and subterranean pathways. The Imageograph conveys the material context of these diverse political actions while attending to the spiritual abstractions that could weave a common thread across such territories of struggle.

For a direct discussion of the three films by Nina Sugati SR featured at the JNAF, click here.

To read more about experimental film practices, read Ankan Kazi’s essay on Ayisha Abraham’s Straight 8 (2005), Anisha Baid’s essay on Kiran Subbaiah’s films, and Mallika Visvanathan’s review of films from VAICA.

All images are stills from films by Nina Sugati SR. Images courtesy of Nina Sugati SR and JNAF.