On Broken Ground: Early Short Films by Nina Sugati SR

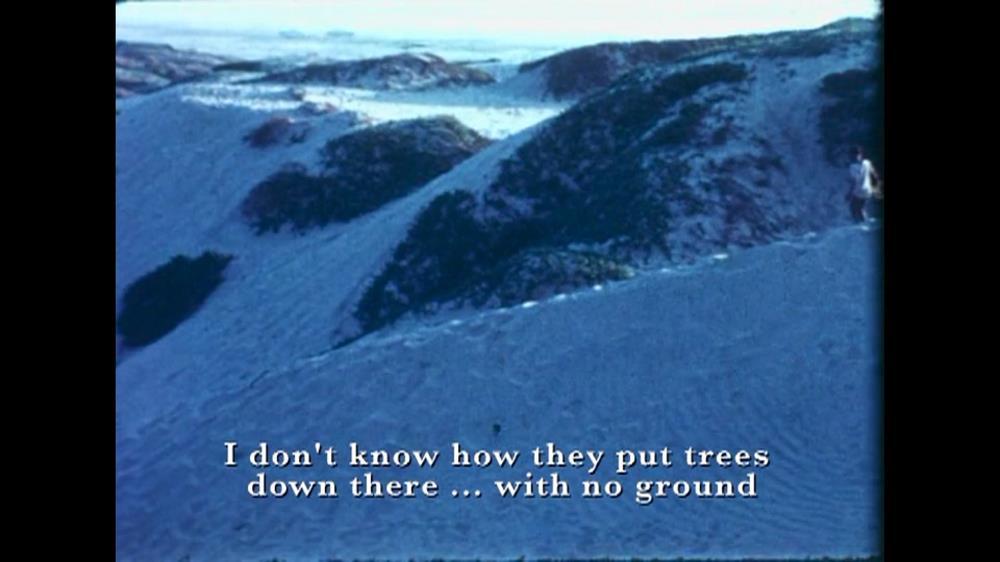

Still from Breaking Ground (1972).

The first part of this essay examined the concept of "Imageograph" as proposed and practiced by Nina Sugati SR (or Nina Shivdasani Rovshen). Rovshen made a series of shorts during her time at CalArts, where she turned to filmmaking after initial training in painting and photography. Titled Breaking Ground (1972), Hope No One’s Listening (1973) and World of All Intelligence (1973), the films stood in for Rovshen’s response to the political undercurrents that shaped counter-culture in the 1970s as a radical, global movement against authoritarian structures across the world. The films were recently part of an exhibition An Exploded View at the Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation (JNAF), curated by Nancy Adajania. A basic framework of anticolonial politics informed her Imageographic approach to subjects that faced repression and exclusion in the American social landscape of the time. Whether the subjects of racism are Black (in Breaking Ground) or Jewish (in Hope No One’s Listening), the axis that connects such disparate social rejects is one of class exclusion due to their very visible poverty. The structural repression that determined the lives of her dysfunctional characters found expression in strange, surreal performances of the self in action and speech. Their alienation, in this instance, resembles the characters’ alienation from the normative functions of rationality and social discipline.

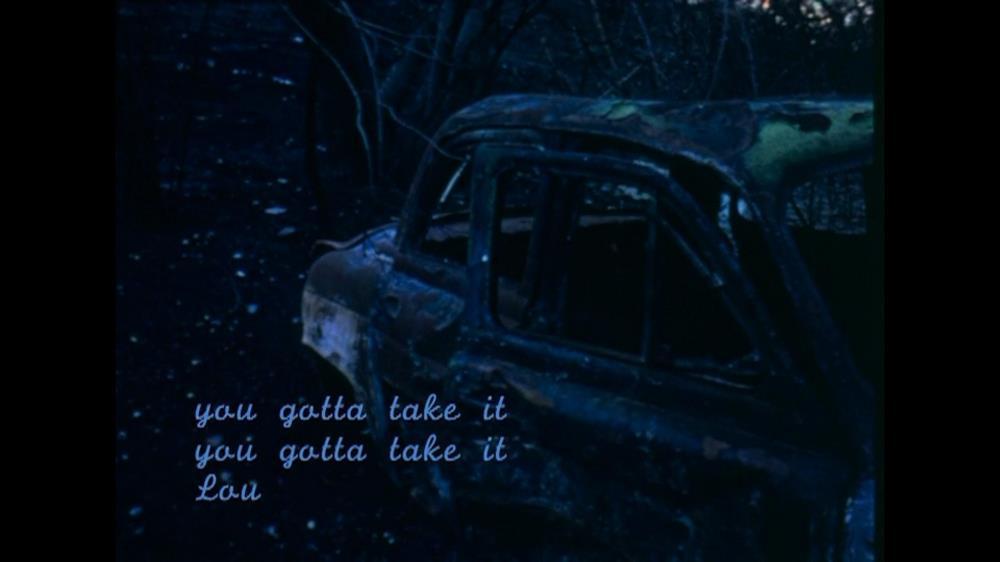

Still from Hope No One’s Listening (1973).

Still from Breaking Ground (1972).

Breaking Ground follows a young black girl with stunted legs due to vitamin D deficiency as she tries to navigate her family life and find a place for herself in the world. Rovshen’s camera probes the family dynamic awkwardly, pushing the ethical claims of ethnographic filming to their limits of acceptability. The film begs the question of whether her commitment is meant to be towards fulfilling the demands of the ideal, removed audience or those of the living people entrapped by her frames. Rovshen focuses closely on the girl’s relationship with her own "dysfunctional" body, intimately capturing her taking a shit and prancing about their unsettled homestead. The protagonist then makes a perilous journey over a rocky landscape, interspersed with scrub and white sands that resemble snow. Once she finally reaches the skirt of a ravine, she declares, “When I looked down… There were a bunch of trees down there, but there was no ground down there. I don’t know how they put trees down there with no ground.” Her poignant voiceover, expressing her fear of being overwhelmed by mice and cannibalism, points towards the tragic imprisonment of the marginalised subconscious by colonial discourses of hegemonic control (so that even a natural landscape suggests the possibility of human manipulation) and racial prejudice. The tone of the film, which uses Rovshen’s Imageographic method, creates an unstable but rhythmic screenscape, as if everything is occurring underwater, which allows her to make a direct connection between the girl’s bodily functions, their productions and their ultimate relationship with the total, consuming fear of a racialised social landscape.

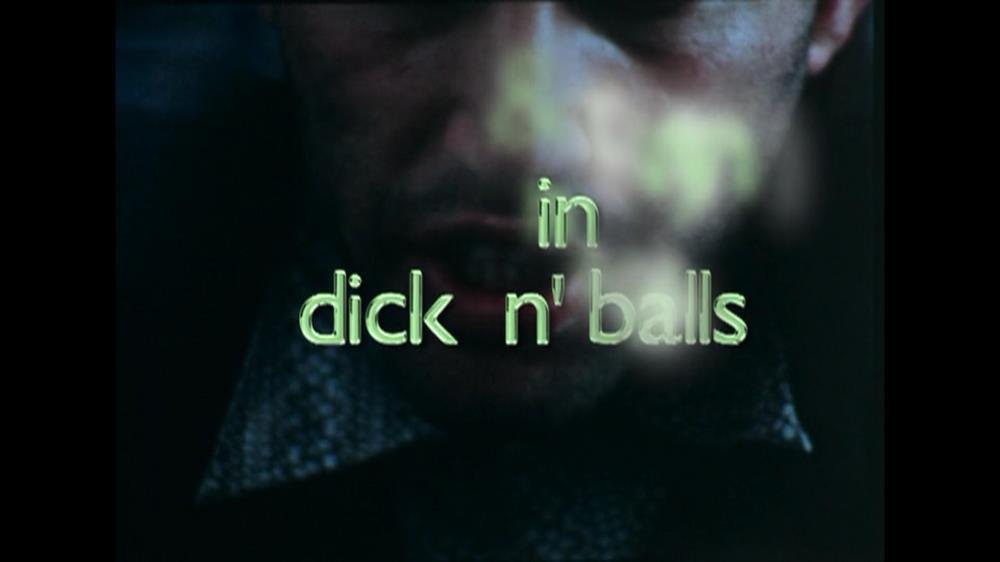

Stan’s obscenity-filled speech is illustrated with text on the screen. Still from Hope No One’s Listening (1973).

These operations are carried out in the other short films as well. If Rovshen focuses on the bodily wastes of her subject in Breaking Ground, it assumes the form of obscene speech and recurrent logorrhea (which Nancy Adajania terms “incessant word-vomiter”) by Stan in Hope No One’s Listening. This film focuses on a few mentally challenged Jewish people attempting to make sense of their social and communal exclusion, which is marked ironically as they appear to conflate normative social life with trenchant anti-Semitism. In their own community of irregulars, however, hope reigns for a more caring, empathetic collective. As the young black girl’s bodily functions led us to the underworld of fears lurking in her subconscious, Stan’s speech takes us into his as he dreams up a werewolf going on a rampage, “...ripping and killing, belching and spurting semen.” Made two years before Miloš Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Rovshen casts the question of “madness” and social dysfunction in explicitly political terms, sketching a more sobering portrait of tenuous solidarity than the Hollywood film’s romanticisation of the same struggle (as one between abstract individuality and institutional authority).

Still from Hope No One’s Listening (1973).

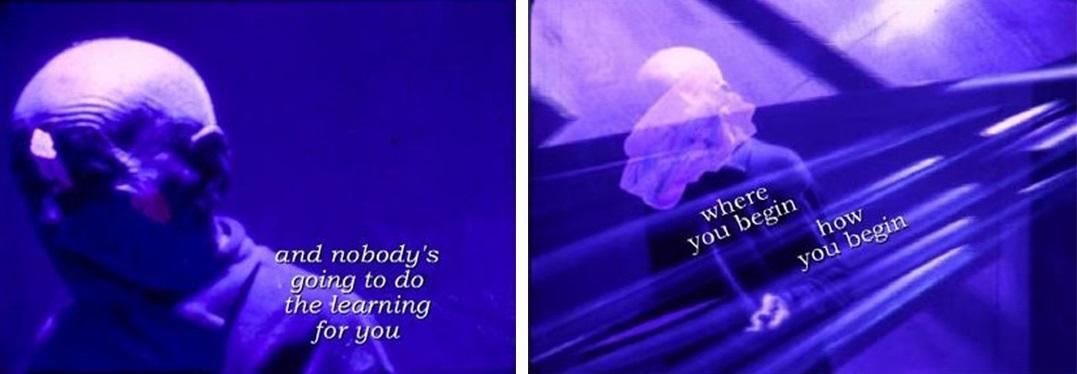

The concept of multiple political pathways, strategic solidarities and keeping such diverse layers available to the audience at the same time informs her short World of All Intelligence. Using a Kodak reversal film, she layers on different elements; in her interview with Heredia, Rovshen mentions, “It’s a five-layer film: Two layers on the camera, one on the oxberry optical printer, one of my paintings, and one of animation.” It is a formal exercise that attempts to open up and subvert realism’s tendency towards framing singular events in linear time. Rovshen’s frames and layered tracks attempt to exceed these assigned roles and refuse the common technologically defined legibility of the film narrative. Together with her other shorts, these bold formal experiments laid the ground for a nascent experimental film aesthetic that would try to define India as a site of anticolonial politics across the world.

Stills from World of All Intelligence (1973).

To read more about Rovshen’s concept of the imageograph, read the first part of this essay by Ankan Kazi. To know more about early experimental films from India, read Ritika Kaushik’s two-part essay on Pramod Pati’s film experiments.

All images are stills from films by Nina Sugati SR. Images courtesy of the artist and JNAF.