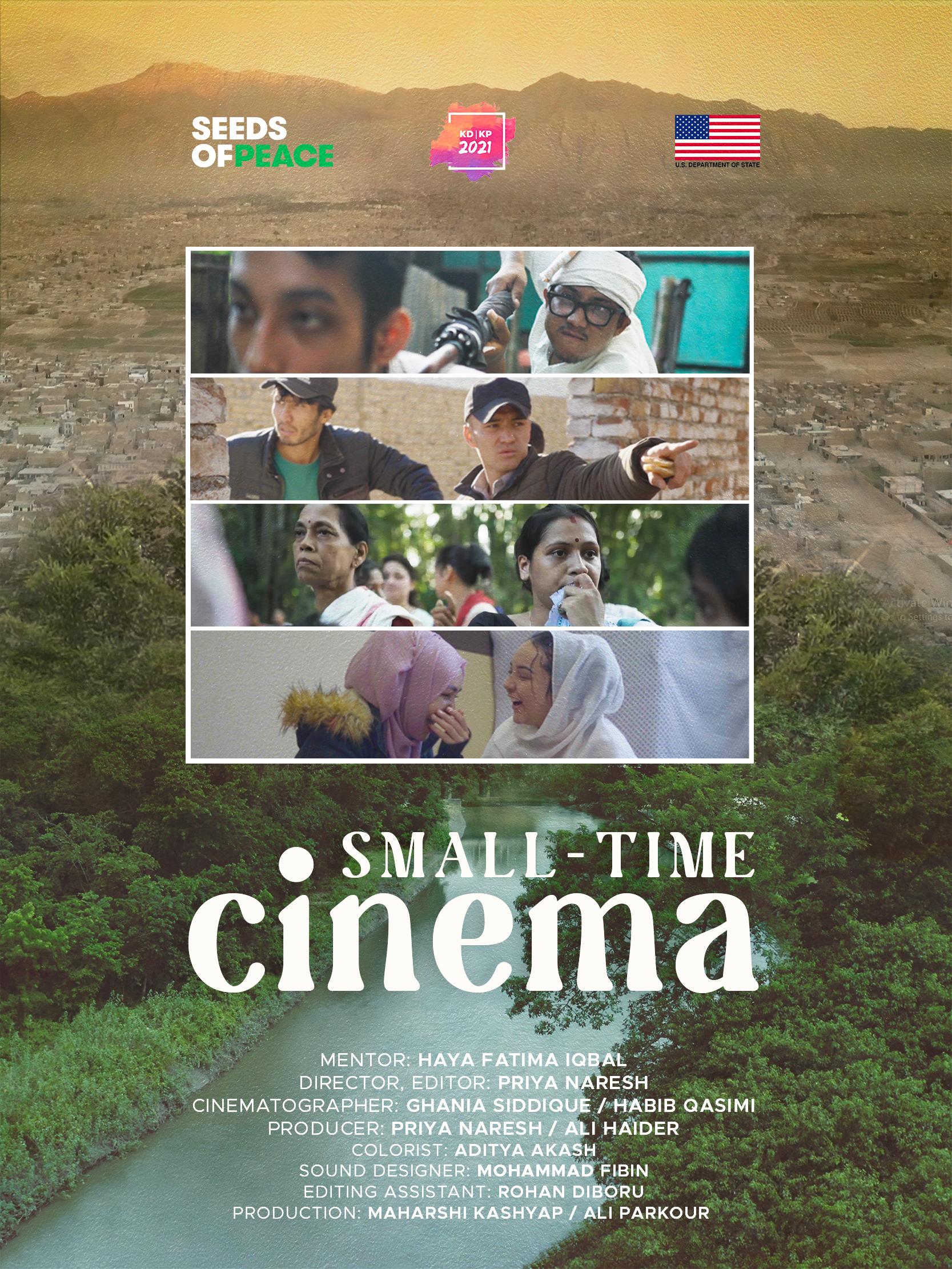

Films Beyond Borders: Priya Naresh’s Small-Time Cinema

In the opening shot of Priya Naresh’s documentary Small-Time Cinema (2022), a man passionately reenacts Suniel Shetty’s iconic line from Dhadkan (2000), “Anjali, Anjali, you can never forget me…” Dressed in what he calls his 'Taliban costume', he then brandishes a sword he had bought a year previously but never had the chance to use. Declaring that today is the day he will showcase his acting talent, the man injects a blend of drama and humour that sets the tone for the entire film. This amusing introduction hooks the audience immediately, providing us a glimpse into the quirky and determined world of these filmmakers that awaits us. The film follows two YouTube filmmaking groups—Assamese Chemistry from Sipajhar in Assam, India, and One Team Media from Hazara Town in Quetta, Pakistan. The film chronicles their journey of creating films about their own communities and issues, while also preserving their language and complex social and cultural histories.

During a post-screening discussion of the film in April at the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art (FICA) in Delhi, Naresh enumerated that the film was part of a fellowship which involved fifteen filmmakers each from India and Pakistan. The participants were divided into groups of two, such that each team comprised one Indian and one Pakistani. Each group then chose to make a documentary, using the unique opportunity of collaborating with their counterparts to depict the respective countries authentically.

Naresh informed the audience that the most significant challenge the groups faced was producing a film without the ability to visit each other's countries. With a limited budget, they had to improvise and hope that the final product would appear as a single, unified film. This process was particularly challenging, as they wanted to ensure the film maintained a cohesive narrative and visual style despite the logistical constraints. When the Pakistani group suggested making the film about YouTubers in Balochistan, the team had to find a similarly remote location in India. They chose Assam because because it doesn’t really have a thriving film industry. Naresh recounted that when they decided to go to Assam initially, they anticipated that their Pakistani friends would join them. They hoped their ideas and approaches would align effectively, resulting in a wonderful cross-border collaboration.

Small-Time Cinema was entirely unscripted, as Naresh informed the audience that they instead focused on deciding the main ideas they wanted to explore. The entire process was quite spontaneous, allowing the project to develop organically based on the footage and interviews collected by both sides. Both the Indian and Pakistani teams shot their footage simultaneously without knowing exactly what the other would capture or emphasise. They had a rough concept for the film, centred on the themes of preserving languages and local cultures, which both the teams were interested in.

Naresh knew an Ojapali artist in Assam who informed her about a nearby group that regularly shot videos. Upon reviewing some of their videos, Naresh found them intriguing. One in particular that caught her interest was of a man who did odd jobs—including massaging—and aspired to create videos about local issues. His goal was modest—to make videos that addressed local concerns in a way the villagers could understand.

The process of making the film was fascinating, as the cross-border crew filmed with their camera while the local team, using smartphones, watched the footage and often inquired about their techniques. The local filmmakers even shot some footage with Naresh's camera and asked for tips on cleaning the audio. Their resourcefulness, determination, ability to innovate while working with financial constraints and focusing solely on the significance of creating their work are portrayed in every scene of the film. This includes the tripod-like setup used by Assamese Chemistry, which Naresh explained was made from scratch by the filmmakers themselves. Since the subjects of the film were themselves filmmakers, they would not often be overtly conscious of the camera. However, they remained careful about what they said in front of it. Naresh recalled an incident in which one of the members of Assamese Chemistry mentioned stealing wood, while another member cautioned him against admitting theft on camera.

When asked about engaging with the Hazara community, Naresh confirmed they did so through the intervention of co-producer Ali Haider, a Hazara himself. Given the sensitive nature of Hazara persecution in Balochistan—Haider's father died in a bomb blast—the community was cautious about being filmed, requesting anonymity to protect their identities. During their Zoom calls, they even heard two bomb blasts within a span of two weeks, which highlighted the dire situation in Balochistan. Despite their fears, the Hazaras were eager to participate, hoping the film might reach India and possibly attract the attention of Bollywood celebrities like Amitabh Bachchan.

Naresh described the project's challenges, particularly shooting in locations they could not visit due to Covid-19. The team had to creatively integrate footage from two different countries while overcoming significant language barriers, as neither Naresh nor her team understood Assamese. With only a week of shooting on a limited budget, they relied on understanding the local filmmakers' vision and how they wished to be portrayed. Naresh admired how the filmmakers stayed connected to their language and community. Her conversations with them allowed her to reflect on her own struggles with migration and note how the Assamese Chemistry crew chose to stay in their villages rather than move to bigger cities like Guwahati, Delhi, or Mumbai.

The film, in many ways, evokes comparisons to Faiza Khan’s Supermen of Malegaon (2008), which follows a group of low-budget filmmakers in Maharashtra. Both films share a similar essence, focusing on grassroots filmmaking and the stories of small communities. However, they differ in context, filmmaking style, geographical locations and the very mediums used by them. Supermen of Malegaon captures the spirit of a small town's dream through a very traditional filmmaking process. In contrast, Naresh's documentary leverages the digital age's tools, with YouTube providing a vast platform for filmmakers and mobile phones becoming instrumental in shoots. Naresh intentionally chose a mobile and grassroots approach rather than adhering to traditional filmmaking methods. This decision underscores a relative democratisation of film production, where technology empowers people to tell their stories, while also making it more accessible and immediate. The film's context and the digital medium it embraces make it a poignant example of how modern cinema can thrive outside of conventional boundaries. Naresh’s camera also gives us access to their personal lives and intimate moments that feel unreservedly natural. The film, with utmost sincerity, also informs us of the filmmakers’ motives, which were primarily entertainment and the pleasure of seeing their own lives and issues represented on screen.

Naresh shared an anecdote about the Assamese filmmaker whose belief in becoming an actor was challenged during conversations with the team. In a scene in the film, he mentions that Assamese people often felt marginalised, being mistaken for being Nepali or Chinese. When asked if these filmmakers were aware of their marginalisation, Naresh explained that it was a gradual process of realisation for them. Initially, they believed they could be actors like anyone else, but over time, they recognised the differences and prejudices they have to face, understanding that they did not fit the typical image seen in mainstream cinema.

Towards the end of the discussion, Naresh mentioned that while they recognise this disparity, the filmmakers are also inspired by successful Assamese filmmakers like Rima Das and Bhaskar Hazarika, who have gained significant popularity in Assam. This local success gives them a sense of achievement and hope, motivating them to continue their filmmaking efforts despite the challenges. Small-Time Cinema honours these communities for creating room for their nuanced histories and traditions, which go beyond and question the concept of a national identity and portrays the sheer joy in the mere act of making a film with effortless grace.

To learn more about amateur filmmaking and digital platforms, read Sagorika Singha’s essays on viral rap songs on YouTube and exploring YouTube as a platform for amateur creators like Dimpu Baruah from Assam.

All images are stills from Small-Time Cinema (2022) by Priya Naresh, courtesy of the filmmaker.