Discerning the Marginal: Trolley Times and Documenting Protest

In September 2020, the Indian government passed three agriculture acts deregulating government wholesale markets, thereby eliminating the Minimum Support Price for produce and leaving farmers vulnerable to the vagaries of a corporate system. The move incurred political opposition nationwide and set off widespread protests by farmers, culminating in what has been described as the largest sit-in protest in history. Dominated by individuals and unions from Punjab and Haryana, the year-long movement unfolded at the borders of the capital, New Delhi, and achieved the revocation of the laws in November 2021. A slate of films around the protests have since been made—Varrun Sukhraj’s Too Much Democracy (2022), Prateek Shekhar’s Chardi Kala (2023) and Nishtha Jain’s Farming the Revolution (2024) come to mind. Gurvinder Singh’s Trolley Times (2023) is among a rich crop of films documenting and exploring the protests. With his latest feature, Singh traces the contours of this landmark demonstration, returning to the documentary form eight years after his last nonfiction work, Awaazan (2016).

Divided into four parts—the titular “Trolley Times”, “Vox Populi”, “The Republic” and “A Village Waits”,—the film drifts from train coaches filled with farmers headed to the protests, to the thick of the demonstrations, and finally into a village whose young protestors were jailed. This narrative ramble is bookended by sequences featuring the newspaper printing press, connecting the stakes of a movement seemingly led by a specific group of citizens to the rest of the country, and the world. Trolley Times takes its name from the biweekly Gurmukhi-Hindi newspaper that chronicled and contextualised the movement as it unfolded, an endeavour aimed at countering the pro-government reportage by India’s mainstream media. In the opening credits of the film, we see the broadsheet being printed, the rhythmic horizontal motion of the press’ rollers similar to the activity of the reaper machine operated by tractors shown towards the end, their literal movement a metaphor for the political one.

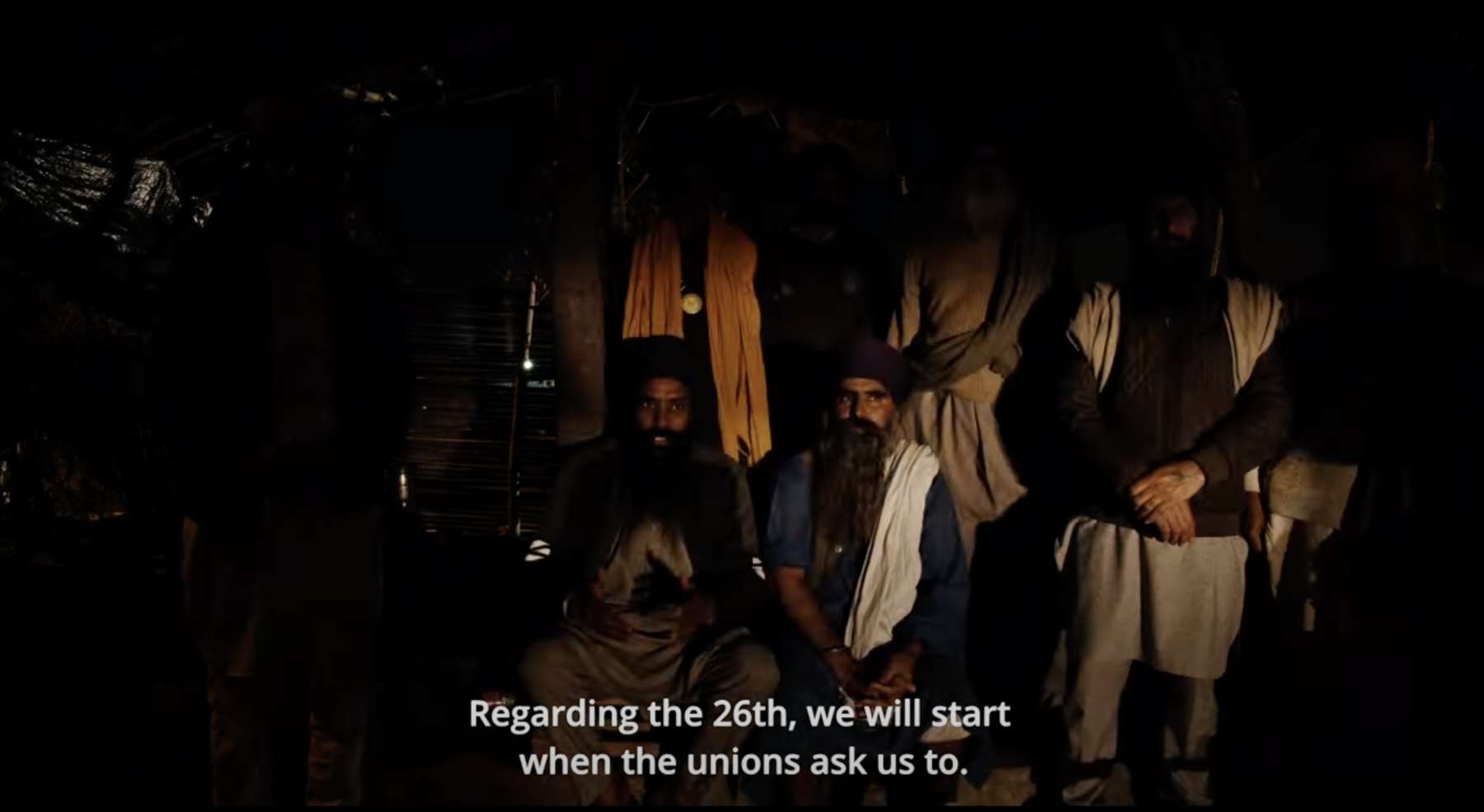

The kinesis of machine, assembly and direct action enters into a dialogue with Singh’s long-established aesthetic of slow cinema, heir to that of New Wave auteurs like Mani Kaul. Vérité style witnessing manifests through intensely toned long takes, long shots and a poetic stasis that compels an engagement with the protracted temporality of the sit-in, all visual cues familiar from Singh’s fiction films. Examples include near-still shots of protestors reading the eponymous paper, a single take observing one wearing his turban, a wide shot of a figure traversing the landscape of the Tikri border, and one particularly striking scene in which a chiaroscuro of farmers being interviewed are strobed by the headlights of vehicles passing over the highway. The dialectic speaks to a tension between kranti (revolution) and shanti (peace) at the level of both image and idea. This is made explicit in the “Vox Populi” section of the film during an argument about the ethos underpinning the protests between two participants (and momentarily referenced elsewhere by the title track of the 1981 Hindi film Kranti playing in the background).

The third segment,“The Republic”, focuses on the 26 January procession of protesting farmers that turned violent. In this section, the production of deep space becomes prominent, through a layering of distances and the bodies of crowds. In one sequence, the tractorcade’s advent from the horizon is further elaborated through shots of and from the perspective of both protesters in the thick of it and police workers surveilling from afar and above, crossing axes and switching angles to capture a complex visual and civic field. It is perhaps the last section, in which the people of Moga’s Tatariawala village are filmed awaiting the return of those imprisoned in the wake of Republic Day, which is most reminiscent of Singh’s contemplative off-centre frames, architectural geometries and off-screen sound from the Punjab of Anhe Ghode Da Daan (2011) and Chauthi Koot (2015). Scenes of families whose men were arrested play out through tableaux of mute confrontation with the camera, outpourings of sorrow and discussions of the predicament at hand. As in the “Vox Populi” section earlier on, the arrangement of interlocutors—facing opposite directions and with backs to each other, for instance, or the gradual closing up on a single speaker—deviates from the norms of the frontal documentary interview, while the unhurried pans and cuts away from the speaker as their voice continues off-camera emphasise their collective spirit. In one scene, the camera watches the children of one of the jailed men playing on a staircase, even as their mother narrates the direness of the situation just out of sight.

The corner is the locus of voice and detail, the source of knowledge in the world of Trolley Times. In one shot, two open windows on adjoining walls face each other like the pages of an open book, the convergence of two lines moving from different directions, the edges, or borders, of possibility. In her essay on the farmers’ protests, “The Gift of Food”, Sarover Zaidi writes, “The prevention of motion in any direction generates a border… However, the aim of the protestors has not entirely been about movement, but to sit in.” It is, she asserts, the experience of a different speed and time. As Singh’s documentary navigates along and across the borders of Delhi, foregrounded by the protests, it engages through its form with the margins of image and discourse. The film is less an archive or chronicle than a measure of a historic velocity, marked at different points by campsite longueurs and spirited agitation. Echoing its beginning, the film’s closing sequence foregrounds the parallels between agricultural and journalistic processes, and the harvest of grains and facts, gauging the times of the trolley.

To learn more about artists who have engaged with different kinds of agrarian practices, read Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Dharmendra Prasad’s practice, Ankan Kazi’s review of Munem Wasif’s Seeds Shall Set Us Free II and Shranup Tandukar’s reflections on Amar Kanwar’s The Sovereign Forest.

All images are screenshots from Trolley Times (2023) by Gurvinder Singh. Images courtesy of the artist.