A Visual Voyage: NFDC's History of Indian Cinema

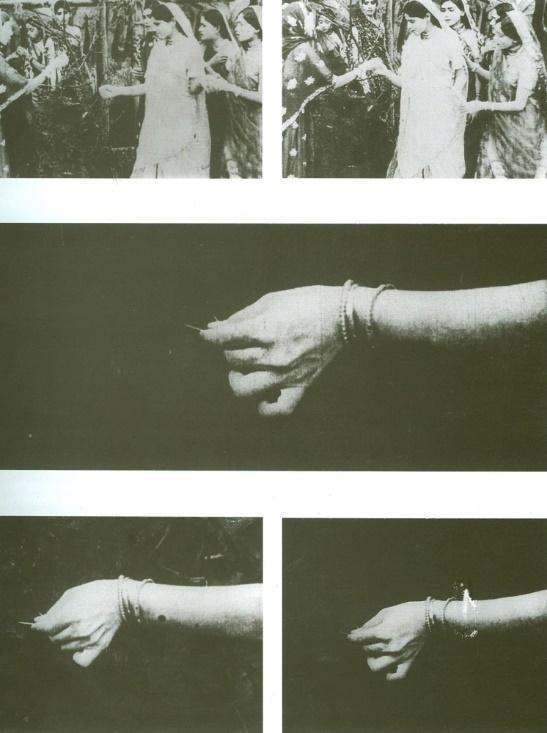

Close up of hands as seen in a sequence from Sukanya Savitri (1922) by Kanjibhai Rathod, Kohinoor Film Company.

Published by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Indian Cinema: A Visual Voyage (1998) aims to provide the Indian state’s version of the historical narrative of cinema in the country. Ravi Gupta, Managing Director of the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) at the time, is credited with writing the Preface, while the rest of the text is unattributed to any single author. Several quotes by public figures and dignitaries from the world of cinema and politics are referenced throughout the book to bolster the arguments, including Jawaharlal Nehru, Ardeshir Irani and P.K. Nair, the famous archivist and former director of the National Film Archive of India. Nair is quoted to present a naturalised pre-history of Indian cinema, sought in indigenous art forms like the “…hand-drawn tableaux in pat/scroll paintings,” and the frequent retellings of mythological stories with the help of “…glass slide images in a magic lantern (that) created the illusion of movement…” Elsewhere, the book discusses cinema’s early years, contextualising Dadasaheb Phalke’s efforts to replace the popularity of films like Life of Christ (1910) with Shree Krishna Janma (Life/Birth of Krishna, 1918). The book says, “Though the spirit behind Phalke’s move was nationalist, he was primarily interested in an Indian film industry with Indian finance which would deal with Indian images exclusively. Phalke was encouraged by his ‘friends in the nationalist movement.’” Indian Cinema: A Visual Voyage encourages the examination of the history of Indian cinema along these lines: imagining the growth or progress of Indian cinema as a parallel commentary on the progress of the Indian state and its nationalist politics towards creating a cohesive Indian identity.

Bibbo, Nayampali and P Jairaj at the set of Mazdoor (The Mill, 1934) by M. Bhavnani, Ajanta Cinetone.

Within the frame of this narrative, the photographs included within the book are assigned a job too, as the text informs us that “The stills that are presented in this chapter will provide insights into the aesthetics of silent cinema.” This photographic evidence, in its turn, is enough to conclude that “…(t)he formal aesthetics of the silent films seems to have developed quite well.” Several photographs are direct views of the sets or studios, in the middle of a production, like the one of the Imperial Films Company, which “had a well-equipped filmmaking infrastructure.” The photographs, thus, document not only an idealistic interpretation of a lost archive but also the minute changes in technology that are presented as the most inarguable evidence of the industry’s progress over time.

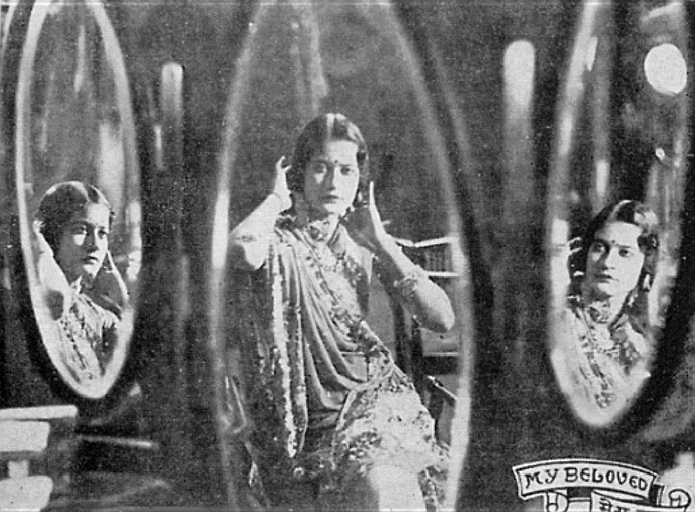

Mera Pyara (1935) by Ezra Mir, Madan Theatres.

The book positions the Indian state as a legitimate speaker for this history and the natural successor to the studio eras of the past. This is partially done by highlighting the literal ways in which studio locations were converted into state film bodies. The decline of the studios (after the Second World War) is mourned as the loss of a legal, organisational unit that gave coherence to the narratives of cinema. The individual producer and his dubious motivations come in for ethical critique: “Soon the studio system started breaking up, paving the way for numerable freelancers whose sole aim was to make money, and more money!”

Sushila (sitting, facing the camera) in Sindbad the Sailor (1930) by R.G Torney Jamshedji, Imperial Films.

After this, easily enough, the book inaugurates the beginning of the “New Wave” with Mrinal Sen’s Film Finance Corporation-funded low-budget film Bhuvan Shome (1969) and Mani Kaul’s Uski Roti (1969), which were made possible by the founding of such state bodies over the previous decade, so that the “Nehruvian cultural vision gets crystallized.” What were these essential bodies that were established to set off this roundabout narrative of legitimacy? The book says,

“Following the recommendations of the SK Patil Film Enquiry Committee set up in 1951, the Government set up the Film Finance Corporation to encourage artistic talent in filmmaking. Besides establishing the FFC in 1960, the Government also started the Film Institute at Pune on the former Prabhat Studio premises. In the cultural consolidation effort, the National Film Archive of India was also set up in 1964.”

This is not to suggest that the book is only a narrow container for the state’s ideas about Indian cinema. The photographs are numerous and often very poetically arranged on the pages. If we ignore some of the interpretive keys presented in the book, the illuminating images can be fruitfully dreamed over by the reader, who craves a better-furnished imagination of the early years of Indian cinema.

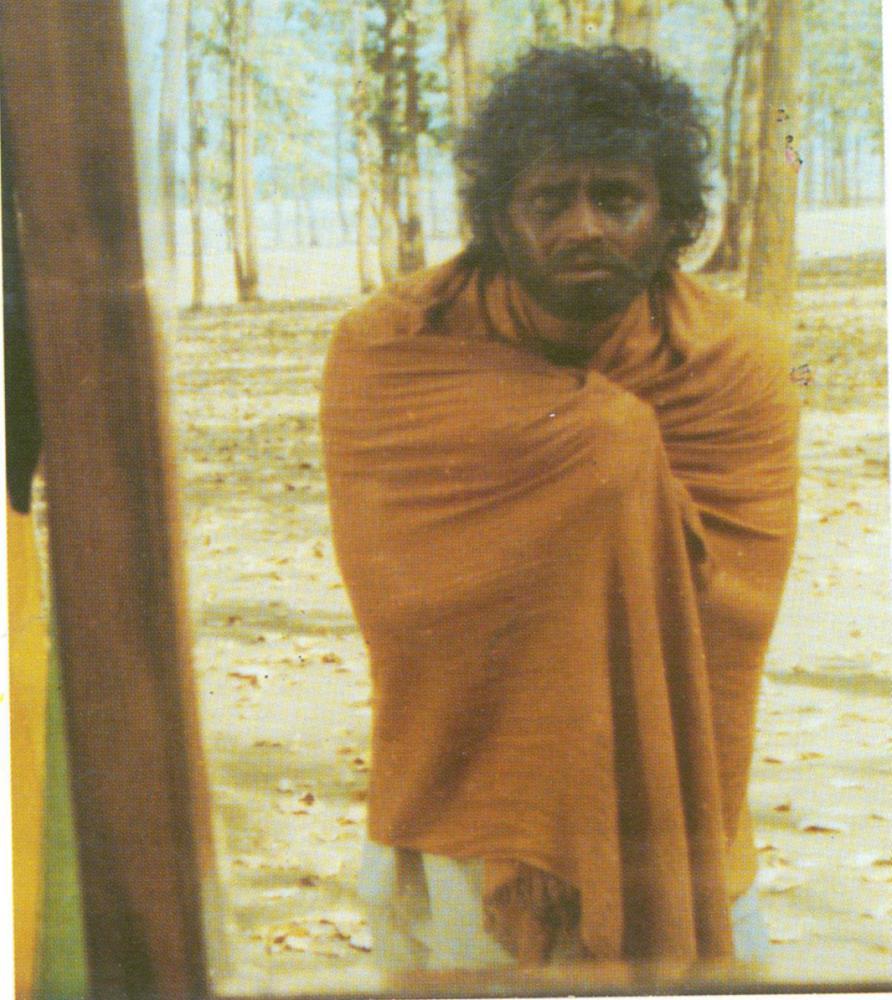

Still from Tahader Katha (Their Story, 1992) by Buddhadev Dasgupta. NFDC productions were given prime place in the book’s recounting of the post-New Wave era of Indian cinema, which included films like Tahader Katha (Their Story, 1992) and Sarisreep (1987) by Buddhadev Dasgupta and Nabendu Chatterjee, respectively.

All images are from Indian Cinema: A Visual Voyage (1998), courtesy of the NFDC and the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Publications Division, India.

To read more about the work created and supported by such state institutions in India, read Ankan Kazi’s essay on the use of photography by the Films Division and Ritika Kaushik’s two-part essay on Pramod Pati’s oeuvre.