Still and Moving Image Experiments: Photography and the Films Division

The experiments with filmmaking and its visual forms in prominent Films Division (FD) works suggest an intermedial, expansive engagement with the film form itself. If we turn to some specific films made by well-known FD filmmakers like S.N.S. Sastry, S. Sukhdev and Pramod Pati, we may arrive at some obvious ways in which photography was employed and presumed to exist in relation to other media—like painting and, especially, the moving image.

Still from Yes It’s On (1972) by S.N.S. Sastry.

S.N.S. Sastry’s film Yes, It’s On (1972), for instance, uses photographs and still images to make its contrasting views of different aspects of Indian reality stand out in stark, bold frames. Many of the images in Sastry’s film were sourced from photographic societies across India. Some of the urban images are eroticised through the juxtaposition of sexualised images of women in “modern” fashion to mark their difference from traditional aspects of Indian life. The film also inserts an image of Indira Gandhi in a montage featuring a wide variety of Indian women—from the urban ones to tribal citizens—seen either working or exercising their franchise at election booths. Such a sequence implies a natural, common identity that is shared between them—that of Gandhi and the practice of democracy. Using dissolves, fade-ins and dramatic juxtapositions, the film manages to elude the use of the stentorian voice-over to move towards a more poetic, impressionable and suggestive reading of images on screen.

Stills from S.N.S. Sastry’s Yes It’s On (1972), which shows images of rural women workers and Indira Gandhi in a field in succession.

In his book Visions of Development (2016), Peter Sutoris calls it an “…experimental montage on Indian modernity”, and concludes his analysis of the film by writing that this “…film’s many layers of dialogue engaged the audience in the process of co-creating the meaning of the film, thus trespassing on the government-citizen insularity that was at the core of the ideology of Nerhuvian developmentalism.”

Still from Yes It’s On (1972) by S.N.S. Sastry, which follows the image of the farm workers and Gandhi. The sequence unites women of different backgrounds through the act of visible labour and of voting.

Photographs assume a significant, self-reflexive method in S. Sukhdev’s film India ’67 (1968) too. They point towards the use of photography as part of the discursive strategies of representing development and the performance of personality and growth for the filmmaker himself in the context of a national community.

Still from India ’67 (1968) by S. Sukhdev, which shows a photograph of the Punjab and Haryana High Court in Chandigarh.

India '67 uses an observational style, employing a series of signs and moving images from across the geography of the subcontinent (especially its built structures like forts, temples and industrial complexes), along with non-diegetic sounds, music and dialogue. Sukhdev utilises different kinds of ideologically loaded editing techniques—like the Eisensteinian montage and the Kuleshov effect—to construct a multifaceted portrait of India experiencing an ordinary day. It was also shot in Eastmancolor, unlike the usual run of FD films, and its experimental language creates a complex, layered image of the country delivered in voices of support, criticism and anti-authoritative irony.

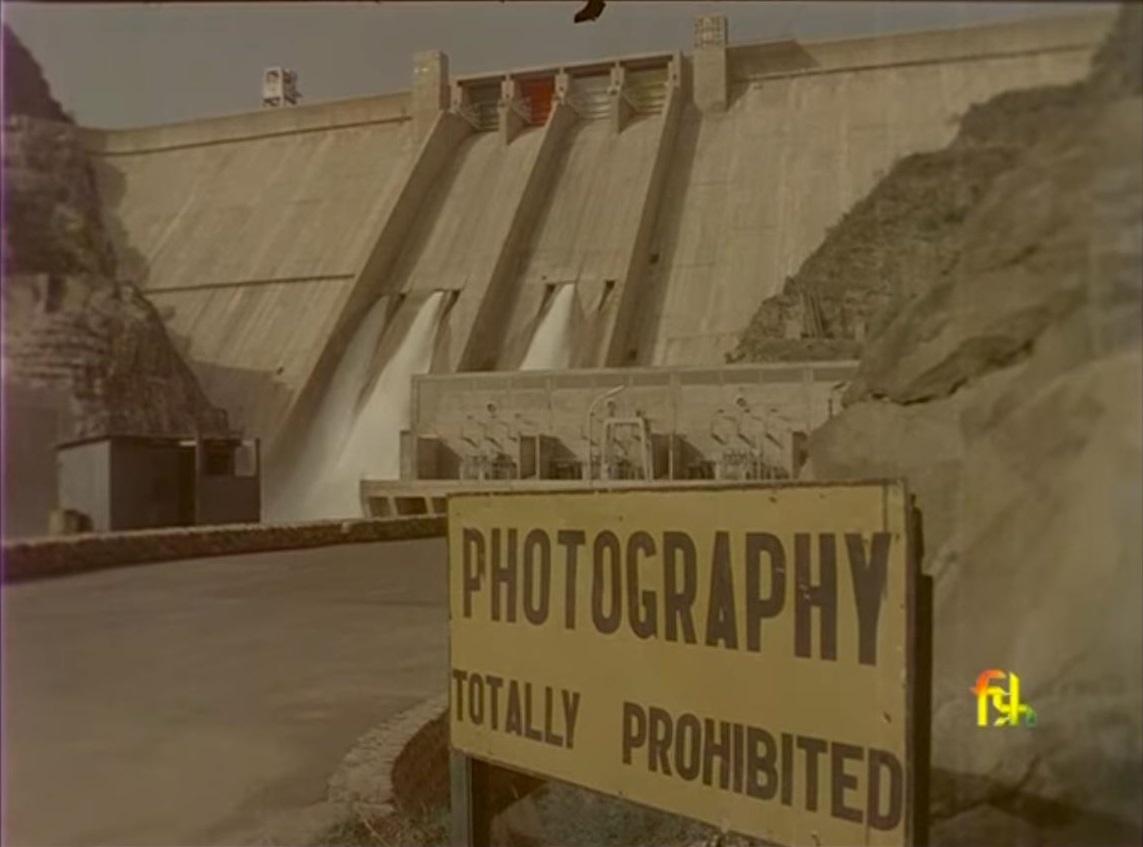

Still from India ’67 (1968) by S. Sukhdev.

As a part of its ironic language, the film features a shot of a quite redundant sign stating "Photography Totally Prohibited" in front of a large dam, which was one of the primary sites of photography for most FD filmmakers like Sukhdev. It points towards the ambivalent status of the image of development itself in India at the time, which required that such structures be photographed only by those whose visions of their significance corresponded with the state-sanctioned one. In another sequence, the filmmaker appears as himself, taking a trip back to his rural home in Punjab. He stands before a wall of photographs that document his own success over the years as a publicly feted filmmaker. They emphasise the route of development as linear and incremental, much like the genealogical progress of a typical Indian identity documented by the photographs (of Sukhdev’s male forefathers and the sacred Sikh leaders from the past, leading up to a photograph showing him being awarded by the Indian President S. Radhakrishnan).

Still from India ’67 (1968) by S. Sukhdev, which shows a framed photograph of the filmmaker receiving an award from the President of India, S. Radhakrishnan.

Writing about this scene in an essay on Sukhdev for Art India, Ashish Avikunthak notes,

“Sukhdev consciously places himself as an ambivalent product of the teleology that he is critical of. This self-effacing biographic insertion is a mimesis of the nation’s struggle he is capturing in his celluloid narrative. The ambivalent trajectory of India into modernity is mirrored by his own uncertain relationship with his living past.”

Stills from India ’67 (1968) by S. Sukhdev. Here, the filmmaker appears before the camera and looks at a wall of photographs of his forefathers in his rural homestead.

The staging of this ambivalent revelation is made possible by the mass of photographs interacting with his oeuvre of moving images, implying their secured place in Sukhdev’s work while separating the filmmaker from it at the same time, marking out a certain alienation of his subjectivity produced by the apparatus of FD’s industrialised, image-making technology.

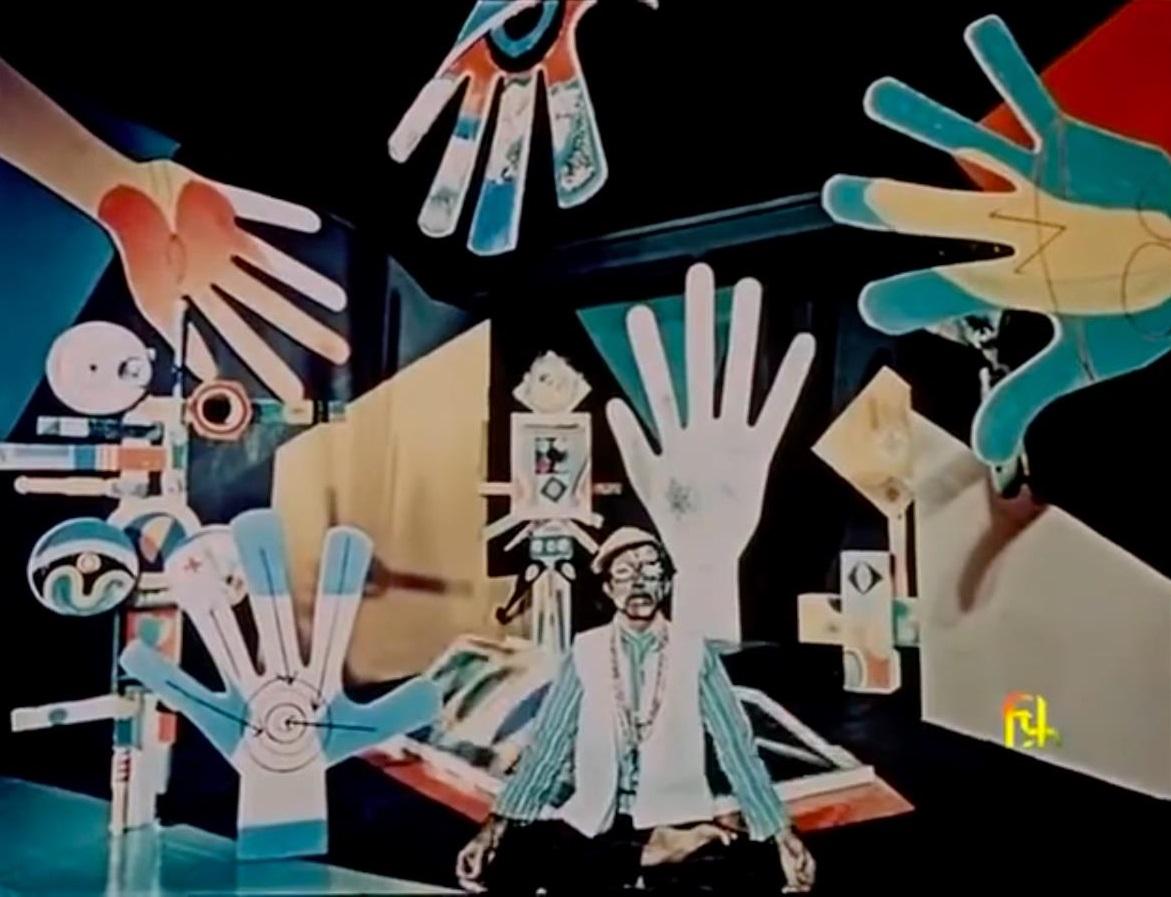

In Pramod Pati’s short film Abid (1972), we find yet another use of photographs. The film uses several stop-motion techniques, typical of Pati, to describe the spatial experience of its subject: Abid Surti, an artist who once painted the walls of his house because he could not afford to buy canvases. Trying to recreate Surti’s experience of “living in a painting”, Pati uses multiple photographs taken from a fixed position to introduce a sense of animation within the image (as it traces his movements) as well as the feeling of being engulfed by one’s own imagination. As an essay in ART India put it,

“He plays with the idea of what it means to have a person ‘live’ within a painting by using the pixilation technique, one in which an individual is photographed in different positions while the camera remains stationary. Especially resonant with Surti’s original project, putting these photographs together in a film makes the individual appear to be animated, allowing Pati to transform the artist himself into a ‘painted’ object.”

Stills from Abid (1972) by Pramod Pati, where we see the artist Abid Surti painting on walls and on himself through successive stop motion shots, animating his actions.

The films discussed here thus present the different idioms of experimentation and mediation of the still, photographic image and technique as they are interspersed with the moving image. Through both the documentary form composed almost entirely of photographs and the use of stop-motion, filmmakers working within the Films Division produced landmark experiments with the medium, particularly under the leadership of Jehangir Bhowngary. As Ritika Kaushik explores in her essay on Pati’s experimental oeuvre, along with Sastry and Sukhdev, the late ’60s until the early ’70s also saw a proliferation of films under the “experimental” category. The use of the “photographic” as a technique, image and interpolation becomes important when considering the experiments in the works of these filmmakers.

Still from Abid (1972) by Pramod Pati. Using stop motion and still photographic techniques, Pati illustrates the experience of the artist attempting to live in a painting.

To learn more about the films produced by the Films Division, read Ritika Kaushik’s two-part essay on Pramod Pati’s oeuvre. To learn more about Peter Sutoris’ work, read Ankan Kazi’s two-part essay on the book Visions of Development.

All images are stills from films, courtesy of the filmmakers and Films Division, India.