Women in the Emergency: Socialist India and the Depiction of Women

When Indira Gandhi declared Emergency in 1975, the Indian state was plunged into a democratic crisis, ultimately resulting in a loss of credibility and a regression from democratic rights. The state sought to overcome this by way of its own propaganda machinery. The use of visual propaganda in the context of Indian politics refers primarily to the large gap in literacy rates between the decision-making elites and the vast crowds (attending rallies or political meetings) from which images of support could potentially be sourced. Images, floating free of textual references but manipulated to present a coherent ideological picture, often took the place of difficult textual histories.

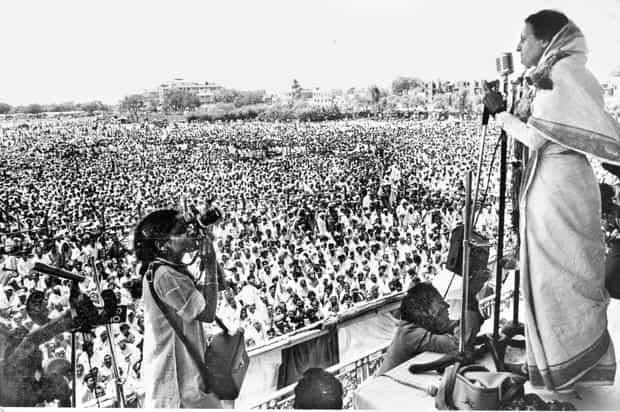

Gemma Scott explores the role of such photographs in the Emergency that sought to mobilise women’s support for Gandhi, her party and the state’s repressive measures, which were repeatedly justified as having been undertaken to protect the rights of “minorities” in the country. In the essay "Putting Women in the Picture", Scott writes, “While women hardly featured in the Congress’s textual commentary on the Emergency, they occupied a significant presence in its visual depictions of mass support for its measures.” She contends that Gandhi’s appeal to women only extended to acknowledging them as a part of minority communities in India that relied on (and, therefore, justified) the state’s intervention and protection, without recognising them as agential, varied political subjects. In this reading of the ideological voice of the state, one may even find echoes in the approach of the Films Division of India, which employed a similar discourse of patronisation to construct the ordinary citizen as a subject population—a plastic object that can be moulded and manipulated by its machinery of representation. The images themselves would often have its subject in frontal presentations, which served to iconise their presence as part of a static tableau, arrayed at the leader’s feet, instead of suggesting their (potential) roles as active, political subjects.

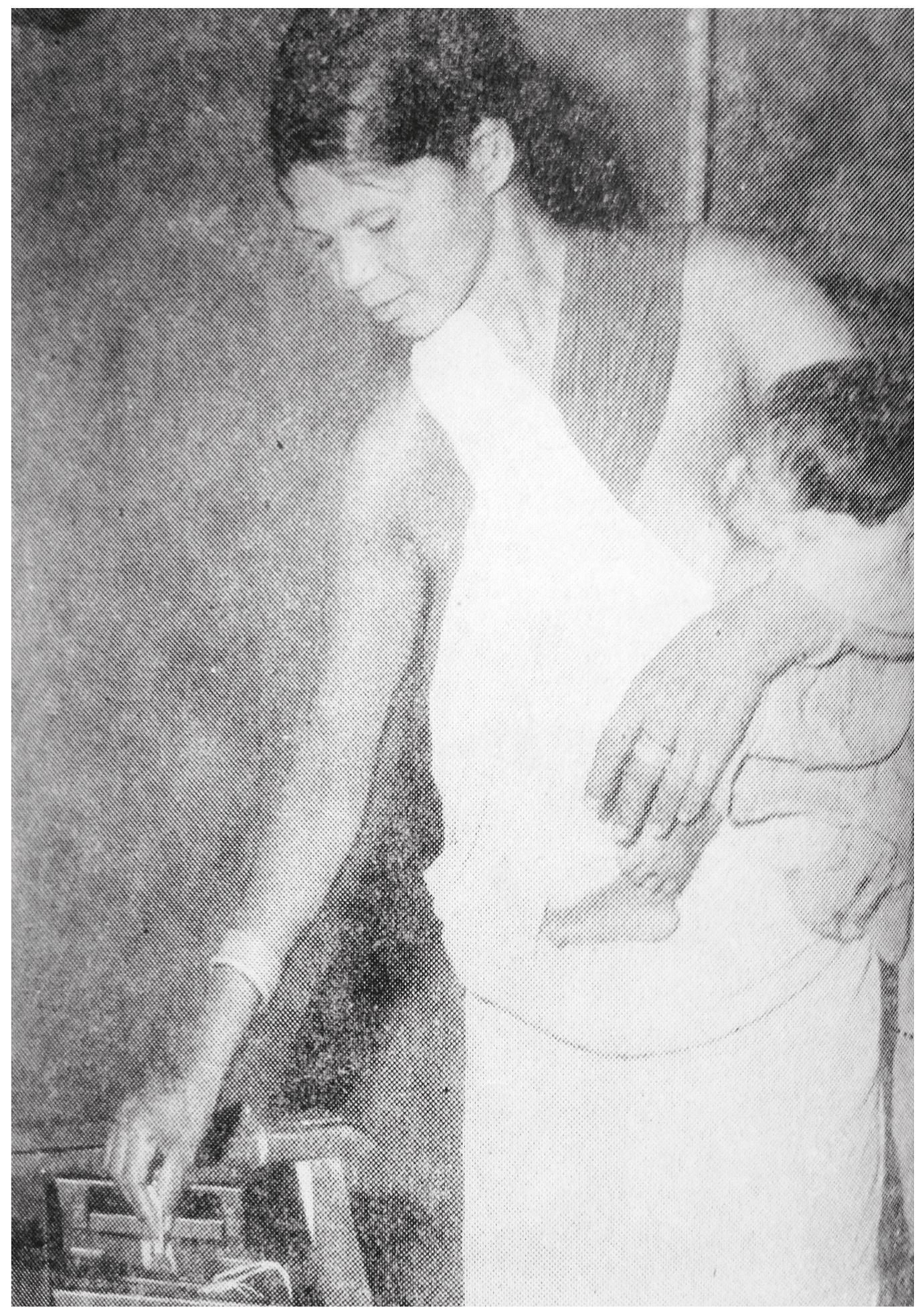

Scott looks through the editions of Socialist India, a Congress Party bulletin “…which regularly used photographs to depict the regime’s popularity,” to show how they used the images of women to bolster their own legitimacy in the eyes of their electorates. The “gendered” photographs produced by them point towards at least two kinds of uses of women’s images. The first consisted of those at the highest echelons of power, led by Gandhi herself as she is frequently depicted iconically in these photographs, looming over crowds or speaking directly to their huddled, silent presence. The second type was, as Scott writes, of ordinary women “…imaged as the masses, supporters of Gandhi at her rallies, and individualized while casting their votes.” Even as these photographs highlighted the vast number of women who participated in rallies and voting exercises across the country, Scott claims that they cannot be described as a “feminist” gesture by any means. Gandhi, in her speeches, frequently addressed women but also reduced them to stereotypical, gendered roles, emphasising their work in the domestic sphere as sacrosanct. As reported in issues of Socialist India such as in an article titled “Women Know Their Sisters”, the talking points aired by Gandhi appealed to the stability of tradition:

“As a mother, I very much understand your difficulties. Housewives have to bear the brunt of running the house. In keeping with Indian culture and tradition you will never eat before you have fed your men and your children. If the kitchen is empty by then you might say, ‘Today is my upvas (fast)’, she says. Smiles dance on the faces in the women’s enclosure and cheers go up.”

Even if the photographs in Socialist India appeared to offer a “feminized visual form,” Scott suggests that, “…closer inspection suggests that (it) used these most frequently in times of political strain or importance, such as in the weeks immediately preceding and following Gandhi’s declaration of Emergency rule, on its one-year anniversary, during the All India Congress Committee’s annual session at Gauhati (sic) in November 1976 and in the run-up to elections in March 1977.” As Scott shows at the end of her article, by oscillating between a form of exoticisation (of tribal women especially) or domestication, the party organs effectively ensured a “depoliticisation” of the roles played by women in the electoral process.

To learn more about the Emergency, read Silpa Mukherjee’s essay on the crackdown on creative liberty in the 1970s.

All images are scans from the Socialist India (1970-78) journal, courtesy of Gemma Scott.