Narrativising the Nation: Visions of Development by Peter Sutoris

Peter Sutoris’ book Visions of Development: Films Division of India and the Imagination of Progress, 1948–75 (2016) is a historical account of the films produced by the Indian Ministry of Information and Broadcasting’s Films Division (FD). It critically examines the films made in the period from 1948, with the creation of the FD, until 1975, when the Emergency was declared, by focusing on the theme of development. Re-watching the films in this archive through this lens allows us to focus on how the idea of “development” was implemented in these films specifically, rather than the wide variety of issues related to different national themes that were also regularly featured in these films. Usually short in length, the films discussed by Sutoris were often screened in cinemas before the main features.

Stills from S. Sukhdev’s India ’67. In order to naturalise the new structures being created for the sake of development, filmmakers tended to juxtapose them with older, popular landmarks that were already familiar to the people.

The idea of what development was and how it was visually represented references a certain awareness of the difference between the material experience of the impact made by certain state planning schemes and memories of such development projects represented through narratives. Taking about the “develop-mentalist turn” in Satyajit Ray’s films, Sourin Bhattacharya writes,

“We may share the narrative of development without sharing the development narrative. The narrative of development may be confined to the materiality while the development narrative has to concern itself with the responses to that materiality… The development narrative of the fifties was much broader in its sweep than the simple narrative of development.”

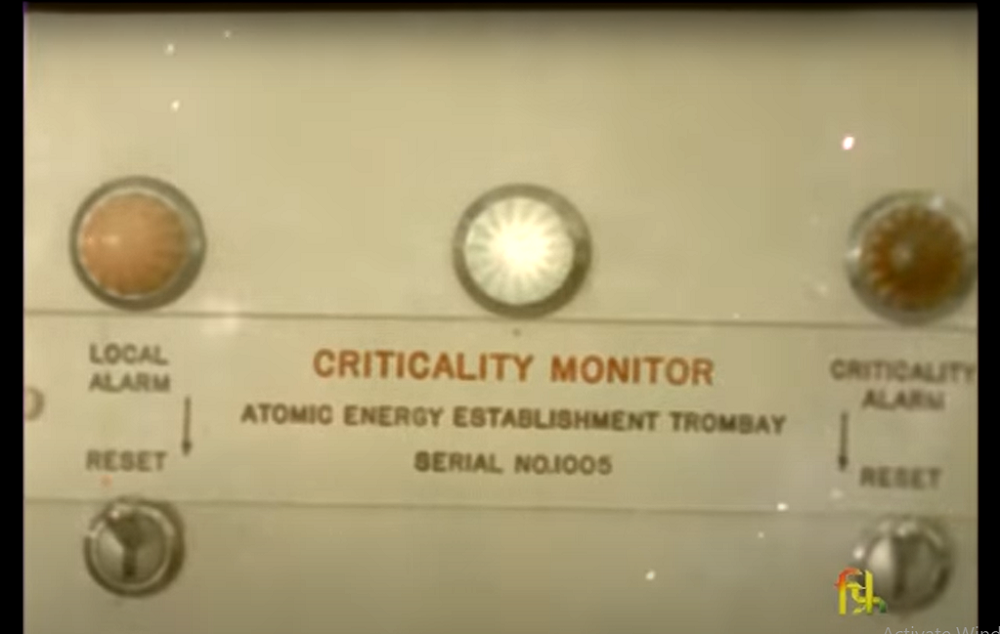

Establishment of the Atomic Energy plant was another significant achievement for the postcolonial government, which was cautiously celebrated by FD filmmakers.

Bhattacharya’s formulation illuminates Sutoris’ own considerations of the FD archive as constituting such a material basis for reconstructing the (“simple”) state narrative of development. The films largely used a recognisable social realist aesthetic. The narrative was usually defined and organised by state-planning bodies or government ministries that commissioned most of the FD films and middle-level bureaucrats who supervised the different layers of pre- and post-production activity. Thus, there was not much “autonomy” on offer for the individual directors, but a mass of institutional attitudes and establishment-driven practices that were reinforced in the making of these films. Whatever exceptions there were, especially during Jean Bhownagary’s tenure at the division, were largely possible by cultivating close relationships between the producers and the filmmakers.

Opening title screen used in most Films Division productions.

Sutoris historicises the FD by questioning the neat separation of colonial modes of filmmaking (for documentaries) from postcolonial ones. He shows us the range of continuities in personnel, institutional values and aesthetic practices that were carried over from colonial filmmaking bodies—such as the Information Films of India (IFI), which consisted of British as well as Indian employees, including figures like Ezra Mir. This aesthetic dichotomy, influenced by individual and collective attitudes toward filmmaking, will be explored in the second part of this essay.

Images of factories, dams and assembly-lines proliferated in FD films on the theme of development. Filmmakers like Sukhdev were aware of the loaded sign that the idea of the factory began to assume in such narratives, and addressed it through modes of irony and self-critique.

All images from various films produced by the Films Division of India. Image courtesy of the Films Division YouTube channel.

To read more about films made under the Films Division, read Ritika Kaushik’s two-part essay on Pramod Pati’s oeuvre.