Images of the Family: Sohail Akbar’s Photo Album

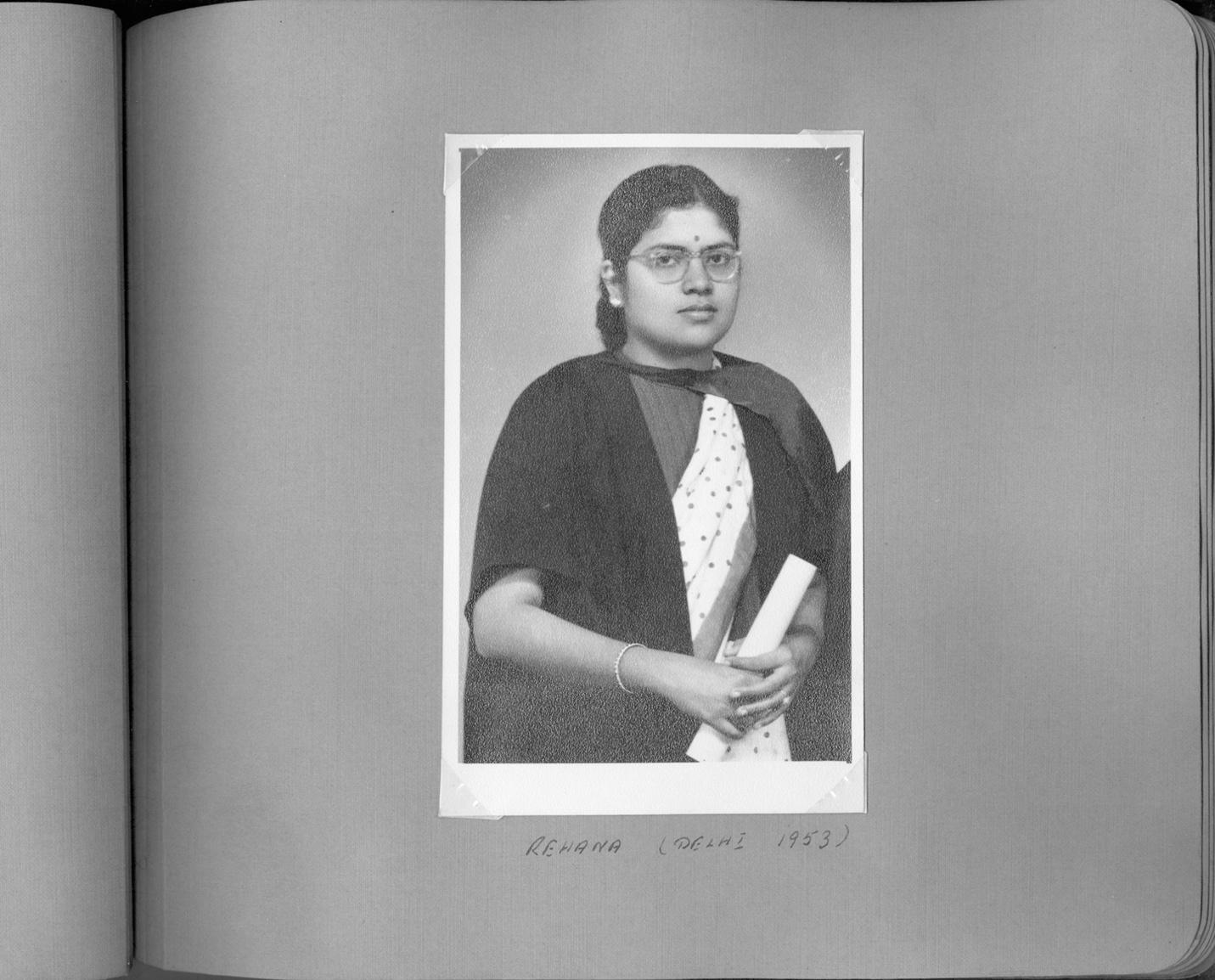

Dr. Rehana Bashir (Delhi, 1953).

As scholars and artists attempt to seek continuity between colonial and postcolonial configurations of personality, photographs have emerged as material traces that can highlight the multiple points of access into such narrative-building exercises. Memory may be the most affective and resonant category that links personal lives, public forms and emergent forces of newness (in experience and practice) that mark any moment of historical passage for a community or nation. Sohail Akbar’s essay “Modern Sensibilities: An Exploration of the Early History of the Nation through Personal Photographs” (2014), attempts to grapple with national historical accounts through the categories of affect, sensibility and perception, as revealed in his own family albums. If the arrival of photography had a limited impact on a small percentage of the subcontinent’s population to begin with, it already accelerated the transformation of Indian sensibilities, with a generation of new aspirations, technologies of inhabitation and emotional investment. These factors determined the changes brought to ways in which the self was seen as a unit of individuality as well as an intrinsic member of a historically located, communally remembered family.

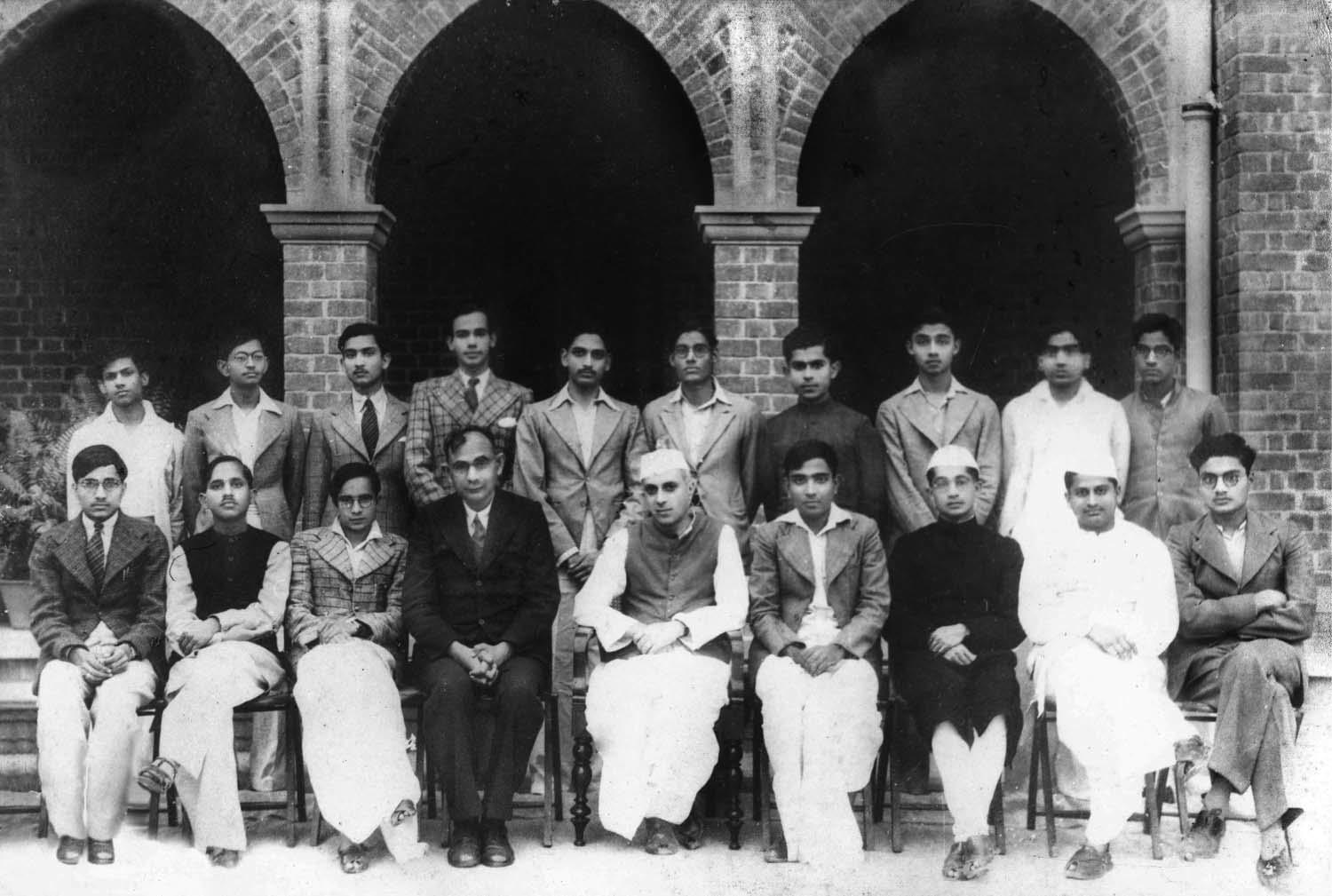

Zia and students with Nehru.

In Akbar’s essay, he considers the photographs of his parents taken before and after the partition of the subcontinent. His father, Zia ul Haq, was a journalist and Communist organiser who came from an agrarian feudal background, which perhaps explains his partial lack of exposure to the technology of the camera. His mother, Dr. Rehana Bashir, on the other hand, came from a modern urban background where she was encouraged to take photographs from an early age. This personal practice remained with her as she grew older and prepared for a career in medicine. Both were invested, in their different ways, in the kind of modernity envisioned by Jawaharlal Nehru (whose photographs were ubiquitous in middle class homes at the time) and chose to live in India, even as several family members left for Pakistan. As Akbar writes,

“This decision was an important marker of his (Zia ul Haq’s) modernity, buffered by his belief in Marxism. For him, a socialist India that offered equality in principle to all its citizens was preferable to living in Pakistan—a state whose very foundation was based on religion. My father’s family album was thus ruptured.”

Prague.

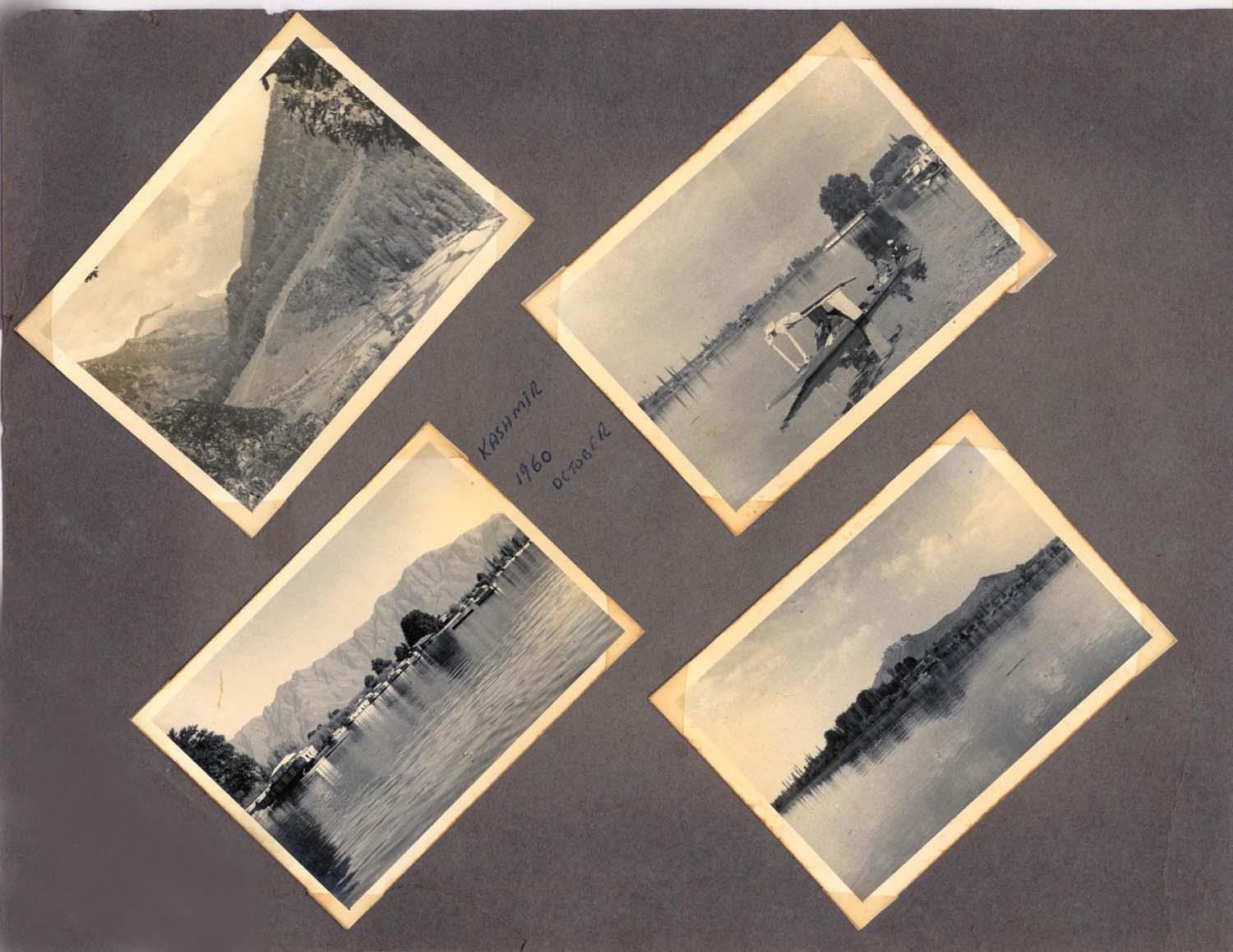

For Dr. Rehana Bashir, postcards asserted their own aesthetic influence. Many photographs taken by her—especially of Kashmir—evoke the standard aesthetic of a postcard image. One can read them as embedded within circuits of tourism and the modern picturesque that determined the economy of such images at the time.

Kashmir Folio (October 1960).

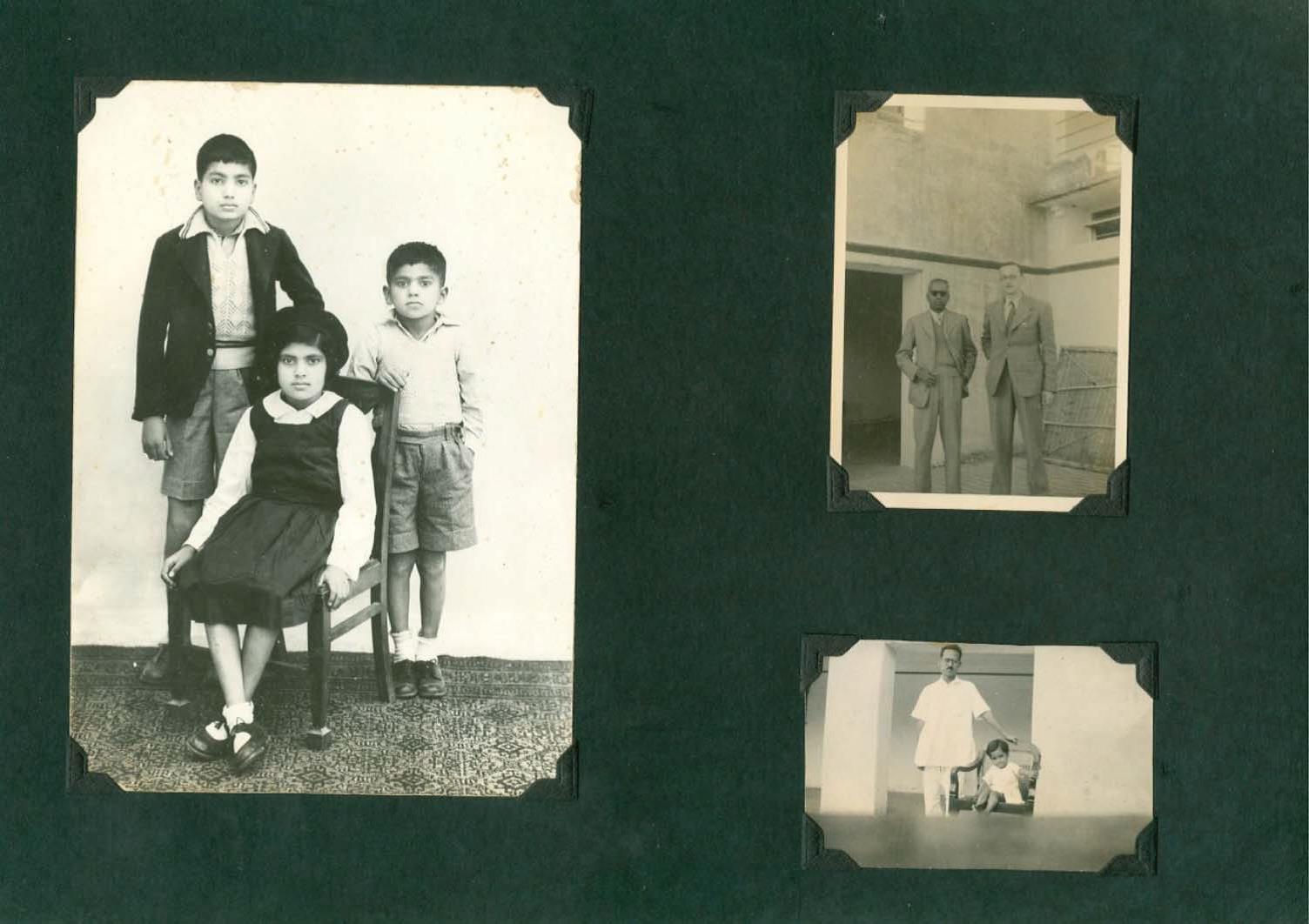

The family album as a whole does not add up to any singular vision of either modernity or the nation that became India. Even the unit of the family, as Akbar demonstrates, was made up of several overlapping tendencies and some divergent goals. The photographs served, in the end, to be little more than a device that could present these performances of difference and familiarity against a common background of kinship. They represent these tensions only fitfully, as Akbar writes that “looking at old photographs, events are recalled in flashes, especially if they have a connection with the viewer.” Instead of the fiction of a seamless narrative, for Akbar, family photographs open up the spaces of discontinuity and anachronism that have marked the lives of people living through such strange and violent upheavals. Even as the surface of the photograph itself seems unmarked by ruptures or disturbances, Akbar narrates the wealth of undercurrents that are activated by his memories, allowing such breaks to assume their organisational authority over these images.

Rehana and two brothers.

To read more about myriad ways of interacting with personal archives, revisit Annalisa Mansukhani’s conversation with Lina Vincent and Akshay Mahajan on their Goa Familia project, Samira Bose’s reflection on Firouzeh Khosrovani’s film Radiograph of a Family Album and Sukanya Deb’s conversation with Siva Sai Jeevanantham on remembering as a political act in Kashmir.

All images from Sohail Akbar’s family album, courtesy of the Akbar family.