Visions of Development: Planning the New Documentary

Visions of Development: Films Division of India and the Imagination of Progress, 1948–75 (2016) by Peter Sutoris situates the aesthetics of progress, planning and other developmental activities across films produced by the Films Division (FD) of India. The first part of the essay examined some of the popular modes of representing development in FD films, largely premised on a simplistic narrative around the state-approved version of national progress. Despite moments of brief departure, such as during the term of Jean Bhownagary, the overarching aesthetic was dictated through the influence of formative figures like Ezra Mir. An Indian filmmaker who primarily worked with documentary forms, Mir was previously involved in the Films Advisory Board (FAB) and the Information Films of India (IFI), before becoming the Chief Producer of the Films Division in 1956.

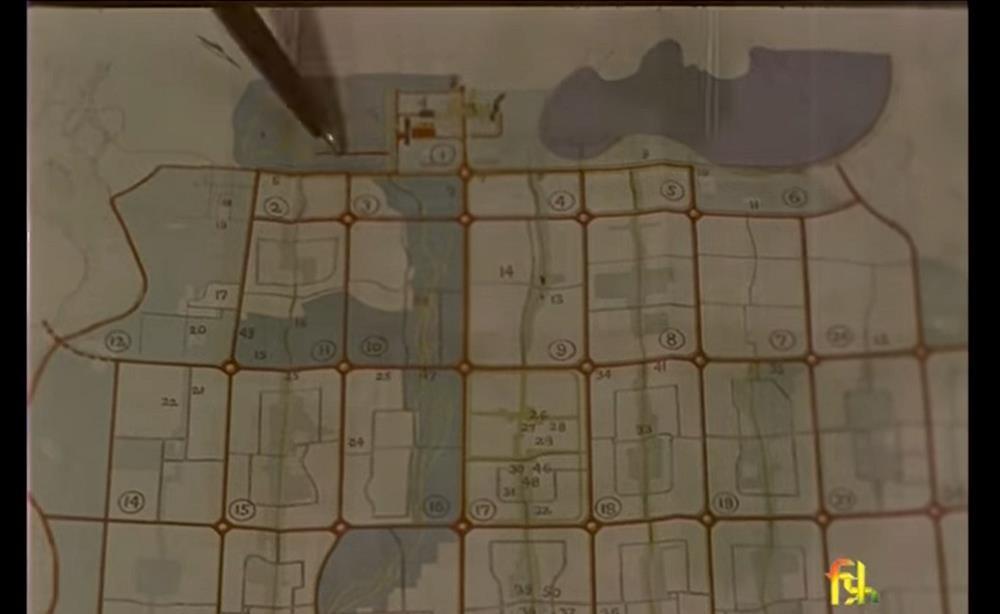

A plan of the city of Chandigarh. Planning activities of this sort were highlighted to emphasise the great role played by planners and developers in the new postcolonial, developmentalist state.

Writing on Mir’s influences after quoting the latter’s preference for newsreel films like The March of Time, Sutoris says, “Among the multitude of documentary traditions he could choose from—from Flaherty’s ethnographic film to Grierson’s social documentary to Vertov’s kino-oko—The March of Time represented a model with perhaps the least amount of audience participation.” It was due to these formative influences that the FD preferred an inflexible structure for the development films, requiring filmmakers to follow strict conventions with distant voice-overs, the absence of ordinary people’s participation and avoiding any criticism for the plans and programmes implemented on a grateful mass.

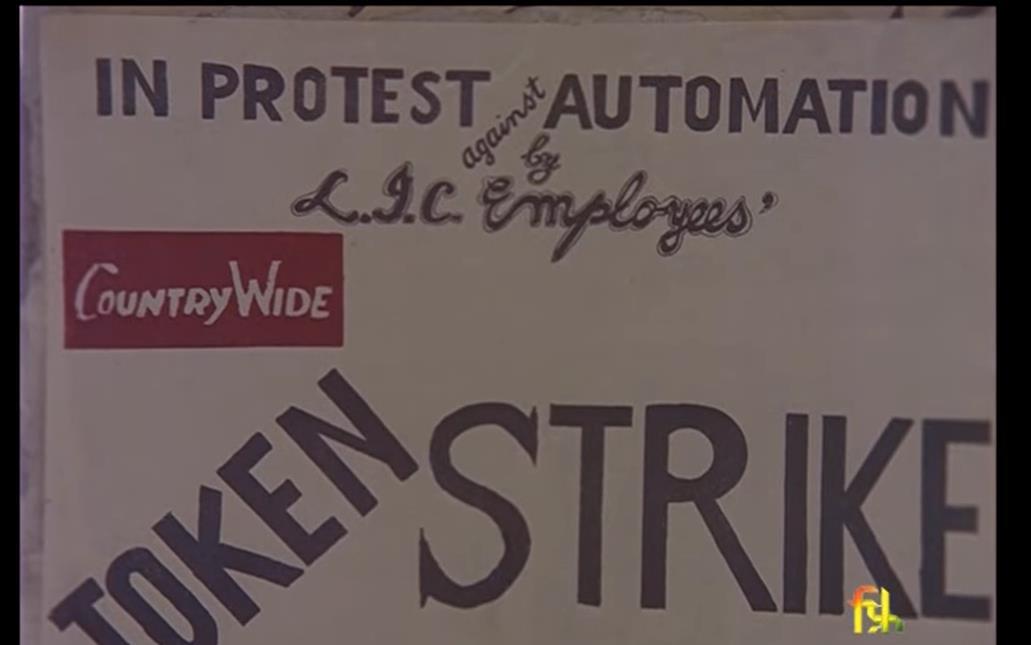

Filmmakers like Sukhdev managed to include frames that explicitly protested against the extractive costs of such development projects in the form of workers’ strikes, for example.

There were, of course, exceptional films made under FD during its run by the likes of Fali Bilimoria and V. Shantaram, who highlighted the poetic aspects of the social realist documentary, and later on, famous filmmakers like S. Sukhdev, Pramod Pati and S.N.S. Sastry. Sutoris suggests that these “inconsistent” visions and the contradictions of aesthetic style were performed on the surface of these films, as much as in their laborious production processes. While some colonial modes were uncritically adopted, others were quietly ignored or re-formulated, sometimes in accordance with developments in radical documentary filmmaking across the decolonising world.

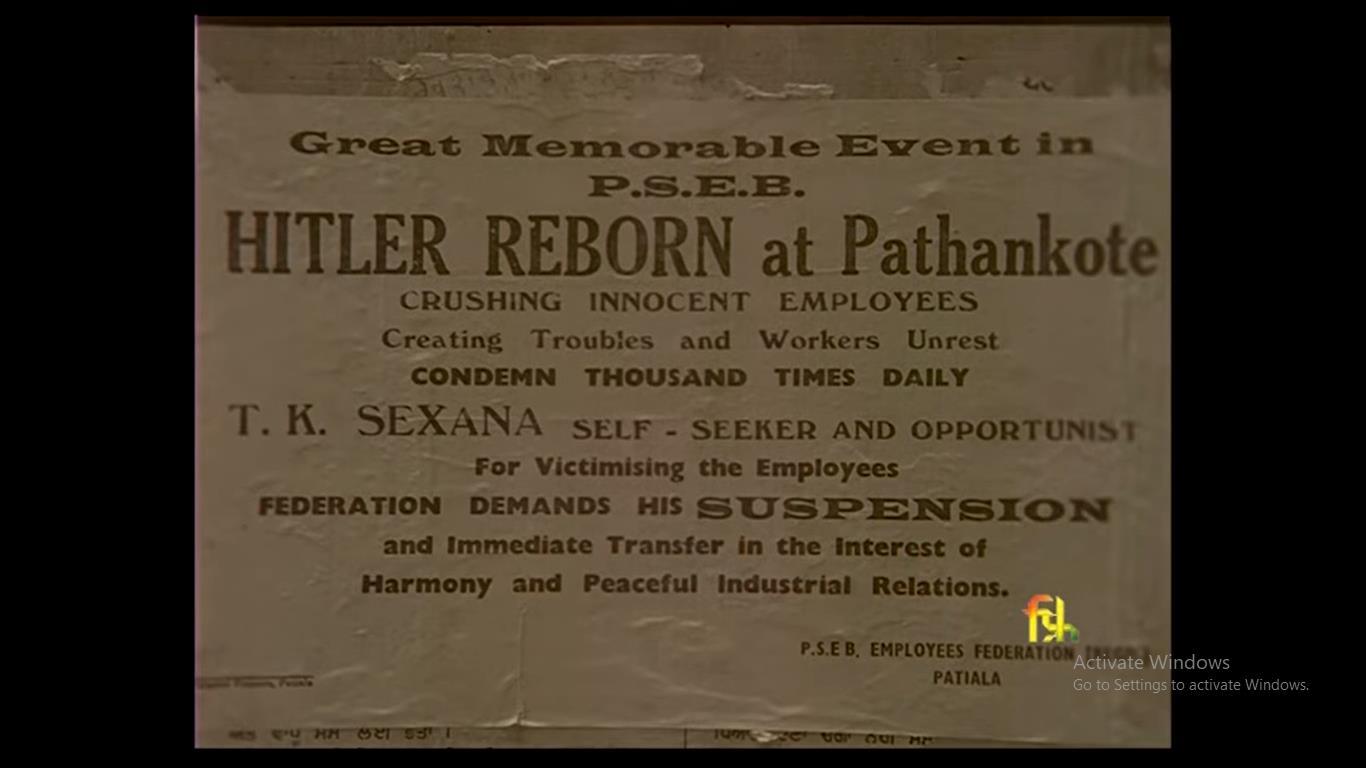

Sukhdev’s inclusion of this poster in India ’67 also hints at the essential elements of his own style, especially dark irony when no direct criticism is possible.

This would extend to the use of lighter camera equipment and vérité techniques that were being innovated during the 1960s. By the end of the 1960s and the early 1970s, independent filmmakers had already started to question the static forms of FD films by making films that were more openly critical of the state’s developmentalist discourse. As Sutoris puts it, “Viewers sensitive to these departures would have noticed that the layering of FD’s films painted a picture of internal tension and inconsistency rather than unity within the organisation and the government at large.” The fate of the developmentalist agenda, therefore, is inherently linked to the primary aesthetic mode of the FD film.

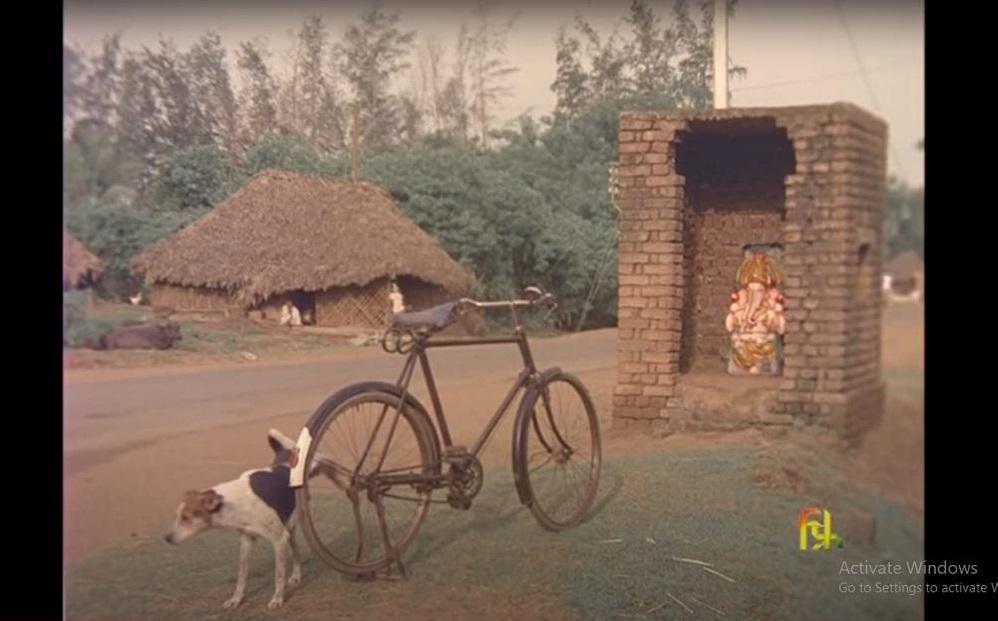

Filmmakers like S. Sukhdev would come to be known for their irreverence, which was frequently depicted in casually observed scenes like these.

All images from various films produced by the Films Division of India. Image courtesy of the Films Division YouTube channel.

To read more about films made under the Films Division, read Ritika Kaushik’s two-part essay on Pramod Pati’s oeuvre.