Fabrications of a City: Maine Dilli Nahin Dekha by Humaira Bilkis

In the short film Maine Dilli Nahin Dekha (I Am Yet To See Delhi, 2015) Dhaka-based independent filmmaker Humaira Bilkis presents the city of Delhi as a set of fleeting moments, imitating most first impressions of the city itself. Bilkis’ reading of the city and its slippery form takes on a rich creative hue in the film, drawing out diverse, multiple realities driven by her exploration of a new urban landscape and its layers. Rooted in her subjective encounters with people, the film—in its 19-minute run-time—is an almost indulgent walk through flashes of coherence, madness and the heat that guides Delhi, allowing us to bask for a moment in Bilkis’ sharp, perceptive eye and her explorations of contexts and happenstance.

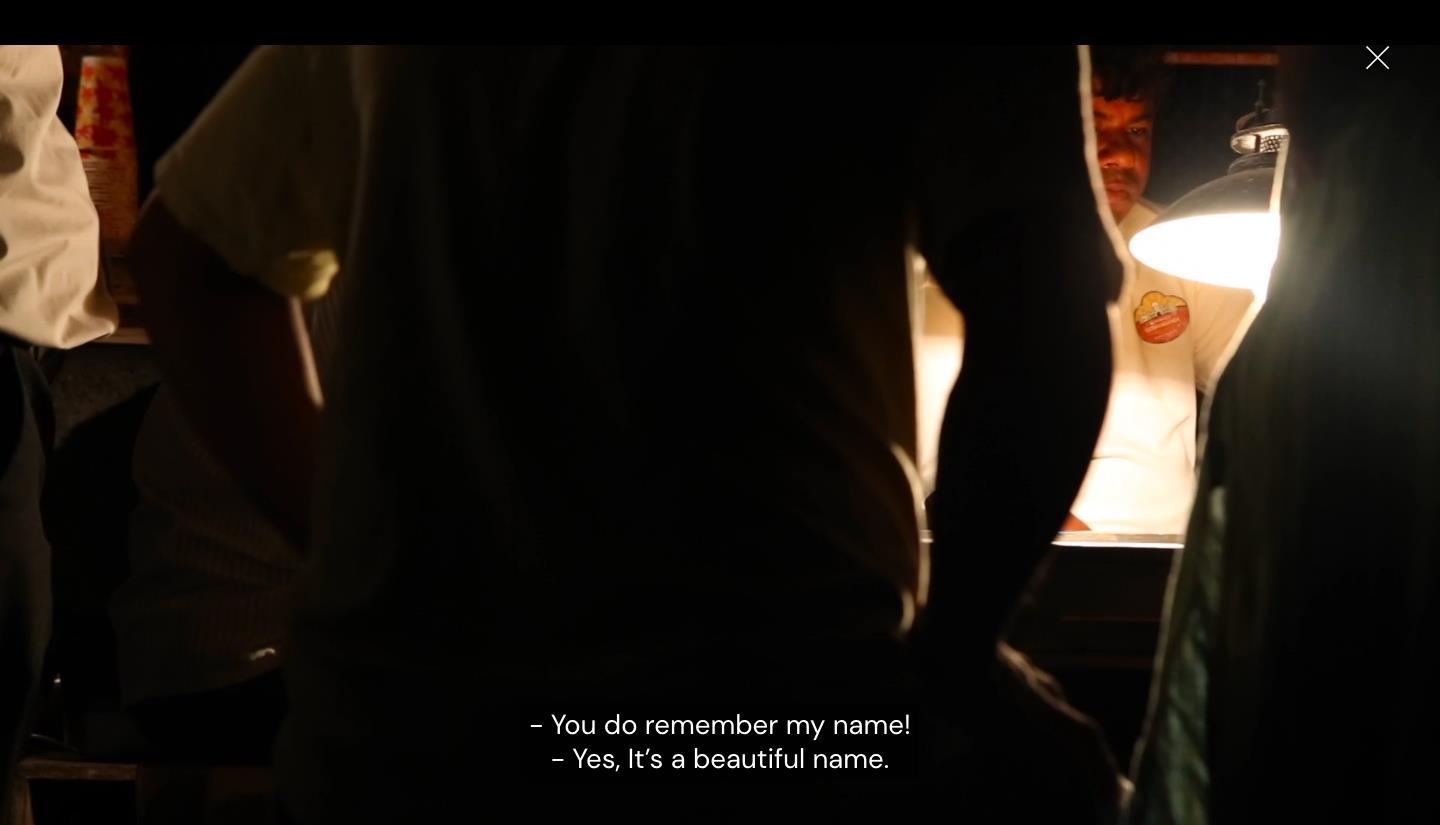

In a scene with a group of men playing carrom, Bilkis responds to a compliment—and a question—about her name.

We are introduced to Bilkis’ Delhi through a series of vignettes. The day is called into being by vegetable vendors, and it is brought to a close by men selling fish as they try to establish its provenance. The film takes us through snippets of conversation: people halt to compliment Bilkis’ name, she negotiates keeping a camera lens for another day, and buses loop through narrations of the city and its histories. An interesting creative choice in the film involves Bilkis’ use of still frames, that intermittently pause and resume movement during scenes, intimating her viewer with an exact image of what she sees through the lens. Through the film, Bilkis does not offer up the immediacy of a linear narrative; instead, her direction moulds itself as she reads her surroundings, framing its mundanity and refusing to offer explanation, but inviting her viewer to freely interpret.

The film scatters, much like the expanse it wishes to document, similar to its inhabitants and their intentions. Bilkis premises imminence—we are allowed into relationships that already exist, suffused with a warm familiarity, into simple domesticity that leaves its mark on walls and basins, across buses that loop and retold histories that never end. Bilkis covers slices of Delhi, and she cleanly excerpts frequencies that speak to her identity as a new Bangladeshi resident—markets, languages, markers of a certain economic strata, and the abundance of tourist sites. In a scene where she presents a part of a group of students on a sidewalk in a still image, we are privy to a debate on mic placements. The film briefly shuttles us into a conversation where Bilkis explains her preference for candid photographs, providing her captive audience a lesson on the properties of camera lenses. With each illustrative segment in the film, the filmmaker demonstrates how her observational capacity allows her to capture the simplest of references to cultural differences and religious identity, while continuing to share her innermost spaces with us.

Bilkis documents a conversation with an elder, possibly around the premises of a mosque, where he explains the relationship of visual representation to Islamic law.

It is interesting to note the scenes in which Bilkis shows herself as the filmmaker-photographer, her image is reflected in mirrors. The inclusion of the filmmaker-figure as a reflection removes the sense of disembodiment that often accompanies the camera and the one who is making the images, both still and moving. In a conversation recorded by Bilkis, we overhear someone thinking out loud and subsequently explaining how photography fits into Islam’s ruling on visual representation. Photography is permitted if it is necessary, the speaker proclaims—for instance, if one is going on Haj—otherwise, it is prohibited as it is sinful to attempt to invoke, capture and therefore recreate life. This latter belief is juxtaposed in the film by the subsequent addendum that there is an allowance made for photographing lifeless objects. One is led to wonder, how does a city translate its objecthood? How is it shared? Do we belong to it, or is it possessed by us?

In the English translation of the title of the film, Bilkis adds a possible expectation and desire with the inclusion of the word, “yet.” “Yet” holds a want and a wishfulness to see, and to be shown what one wants to see. As a conjunction, yet is a linkage; but as an adverb, it is persistently stewing in time, defining an action in the past, present or future. With similar foresight, Maine Dilli Nahin Dekha/I Am Yet To See Delhi asks after the way sight is programmed into novel encounters, the way it—both sight and the city—invites inhabitants to subsist within its (en)coding

Bilkis fragments her time in Delhi with snapshots of residential areas, her domestic space and her daily activities, almost as a record of the transience of lives, time and spaces in the city.

Bilkis’ film relativises the apparatus and the distance it creates between the photographer and its subject. The camera is a tool; it is dismantlable, and it is pointed towards that which we want to see. Additionally, it documents what it wishes to record as well. In a scene from the film, a child narrates his way through a sketchbook, inviting Bilkis into his inner world of imagination. As the camera moves over the sketchbook, the audience is shown what he desires for them to see. In this showing and being shown, Bilkis witnesses the city—its ambient sounds, sunlit interiors, drawings of the Taj Mahal, Bangladeshi fish, etc.,—and leads us to see how people occupy space. Sight is performed through gestures, and the film is driven by the notions of the gestures we wish to make. Bilkis frames the city in a series of temporal glitches, floating through time on its historical past that is swallowed whole by the people who move through it, oscillating between belonging and possession, and sometimes, on a rare occasion, namelessness.

To learn more about the representation of Delhi, read Annalisa Mansukhani’s reflections on Aperture’s issue Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In (2021) and Ankan Kazi’s review of Hum Dekhenge curated by Aasif Mujtaba and Mohammad Meharban. Also, view a series of curated albums featuring Gauri Gill’s Nizamuddin at Night and Taha Ahmed’s A Displaced Hope.

All images are stills from Maine Dilli Nahin Dekha (I Am Yet To See Delhi, 2015) by Humaira Bilkis. Images courtesy of the artist.