Re-Viewing Company Painting: Charan Singh’s Queer Lens

How did company paintings depict queerness in/of Indian subjects? Curiosity about the new world brought many travellers, artists and collectors to the subcontinent’s shores from the seventeenth century onwards to document what their countrymen had never seen before. While landscape painters like Thomas and William Daniell painted “picturesque” ancient ruins and landscapes, Flemish marine painter Frans Balthazar Solvyns illustrated and categorised, among other things, castes and occupations in Indian society in Les Hindous (1801–12). Although he was not a company painter, Solvyns also included the ‘hidgra’ or hijra in the second volume of Les Hindous, calling them a “vile class of beings.” This sentiment was echoed by the colonial government, which attempted to censor their ways of livelihood, viewing them through a moralistic gaze, as Jessica Hinchy writes in Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India (2019).

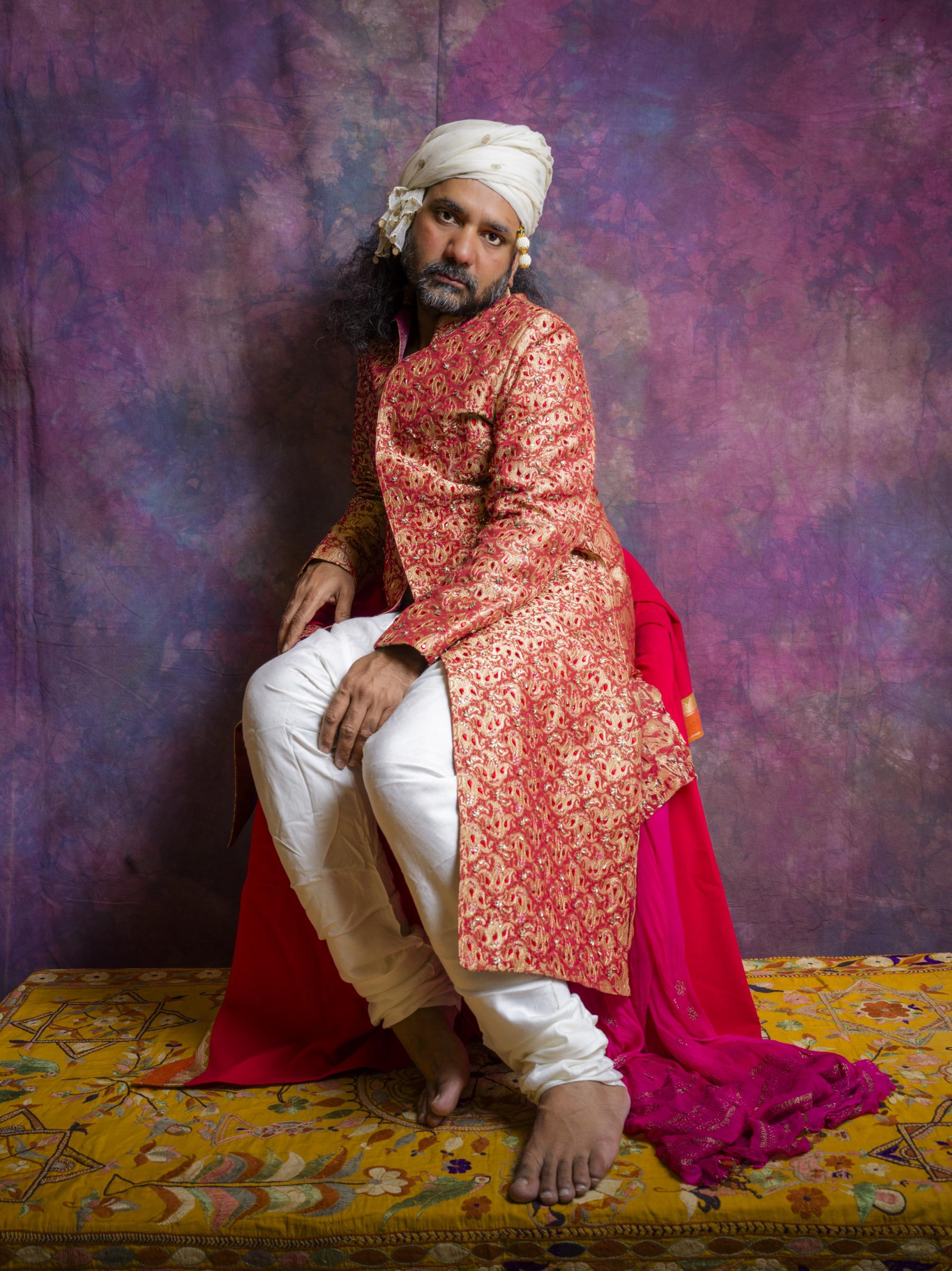

The Looker (2023. Archival Inkjet Print, 53 x 40 inches).

In his first solo exhibition, The Promise of Beauty, at The Art House, UK, Charan Singh reinterprets company paintings from a queer point of view. Often collaborating with his partner, the photographer Sunil Gupta, Singh works across photography, video and text. Singh engages in autofiction through his self-portraits as he writes his own lower-class background into the images, reworking and representing figures from the same class location. While company paintings aim, as Mildred Archer writes in Company Paintings: Indian Paintings of the British Period (1992), to “objectively observe” the Indian scene, for Stuart Cary Welch, depictions of the lower classes typified in these paintings lacked individuality, as he writes in Room for Wonder: Indian Painting During the British Period (1978). Their occupation or class, and sometimes caste—European artists often confused the two categories—remained the only markers for their identity, and they were never pictured engaging in any other activity beyond their work. Indian artists were also trained academically in such styles of painting, emulating these sterile depictions of “types” of the Indian demographic, even abandoning brighter colours, as Archer notes, in the hope of more commissions. In his book, Welch includes an interesting portrayal of gardeners at work by an unnamed artist, where a play of perspective makes the workers invisible even as they tend to the gardens in the foreground of an immense Palladian palace. In his self-portrait as one of these almost invisible gardeners, Singh meets the lens’s gaze as he stands in the moonlight, holding a watering pot, almost abashedly. His gait and the redundancy of gardening in the dark imply an amorous rendezvous in an otherwise typical scene.

The Gardener in the Moon (2023. Archival Inkjet Print, 53 x 40 inches).

Through his interpolated self-portraits, Singh gives these unnamed figures an identity beyond their occupation and typified representation. Instead of the sharp contours of watercolour, these figures stand against washed out backdrops, which Singh procured from India. Reminiscent of early studio photography, the focus thus shifts from the background to rest solely on the figures. Desire takes a performative turn in The Traveller (2023), who loops an umbrella around his arm with a finger on his chin, once again pictured in the moonlight. This gesture is encoded not only with a kind of feminine coyness, it also recalls a theatrical pose similar to what someone like Sridevi or Rekha might strike during Bollywood song sequences. Both of these actresses are also often considered to be part of canonical queer expression in South Asia. In another of Singh’s works, Garden of Eros (2017), a gay man discovers a cruising park after following another man who was singing the favourite Bollywood song “Lal dupatta malmal ka” from the eponymous 1988 film. Singh thus ties a thread between the present and historical time, alluding to and allowing the space for a similarity in experience for his queer ancestors.

The Traveller (2023. Archival Inkjet Print, 53 x 40 inches).

Singh worked as an AIDS activist for many years before moving to London in 2012. It was during his social work that he learned English. Working in grassroots communities, Singh realised that it was the economically underprivileged sections of society who were the most affected, considering the lack of information available to them. In a video titled They called it love, but was it love? (2020) that accompanies the portraits, a person pronounces the full form of AIDS—the words of an alien language running unfamiliarly over their tongue. The text, then, becomes significant in terms of access. In a portrait work titled The Reader (2023), a man lies on a bed, caught in the act of reading a book. Such figures engaging in leisure through reading were not frequently depicted in company paintings, much less depicting someone from the underprivileged class of society. Mughal miniature paintings—often considered a point of influence for the developing company painting style—had relatively more figures reading or writing scripts, most often found in the borders of manuscript paintings. Such a depiction of intellectual work was seemingly not a point of representation within the company painting idiom. Unlike the stiffness in body language and posture found in portraits by artists like Solvyns, Singh’s figure is comfortable—his clothes riding above his leg, once again shrouding the image in desire.

The Reader (2023. Archival Inkjet Print, 40 x 53 inches).

Company paintings were illustrated from a colonial gaze, often encompassing a clinical or anthropological purpose. That was certainly the case for the arrival of photography to India, often wielded in visual surveys of the subcontinent, as represented through commissioned albums such as The People of India (1868–75) volumes. The gaze of the camera in Singh’s portraits, once a colonial instrument of documentation, turns into something more personal. In his portrait titled The Languishing Prince (2023), a man, possibly a palace worker, emulates the prince by wearing his clothes. Unlike the formal posture reserved for royal portraits, Singh bares his emotions by leaning onto the wall and gazing intently at the lens, almost turning the camera into the eyes of his lover. Royal portraits of kings, by artists like Tilly Kettle, highlighted their taste for finery and jewellery, which Manu Pillai writes became a tool for the British to criticise and attribute a “femininity” to Indian rulers, comparing them to dancing girls based on their outward appearance. Here, Singh reclaims this accusation by play-acting as a royal to present a triptych of figures through the presence of a bathing figure and another figure, which parts the curtain furtively as they look outside. The image presents a narrative of desire, with the presence of the lover ever implied through their absence in the image. For Solvyns, dancers in royal courts had dubious morality, which he ascribes to the luxurious and degenerate life of the Mughals. References to dance and performance linger in The Looker (2023), as an anklet bell, usually worn on the feet of dancers, encircles the artist’s wrist. The amorous perspective of the lens allows it entry in extremely private spaces that company painting artists would never have ventured into.

The Languishing Prince (2023. Archival Inkjet Print, 53 x 40 inches).

To learn more about artists interrogating queerness through their work, read Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on the works of Sunil Gupta, Alfa Shakya’s albums selection from the work of Arhant Shrestha, and Mallika Visvanathan’s interview with Sandeep TK. To read more about practices that interrogate the colonial archive, read Pramodha Weerasekera’s essay on Anoli Pereira and a selection of painted photographs by Renluka Maharaj.

All images are from The Promise of Beauty (2024) by Charan Singh. Images courtesy of the artist.