In Solitary Confinement: Safe Haven by Gopa Trivedi

In 2014, artist Gopa Trivedi lived a few kilometres away from the Lahore High Court premises, where a woman was stoned to death for choosing to marry for love, as opposed to arranged marriage, which is customary for women from her background. The incident was later reported to be an honour killing that was incited by a group of men, which included the woman’s father, brothers and former fiancé, her cousin. One cannot help but wonder about the woman’s state of mind as she waited for the courtroom doors to let her in, a place that she thought would be able to help her. Regardless, the stoning occurred—the law could not protect her from the severe social and cultural constraints. Trivedi remembers this incident in vivid detail, recalling the nuances of being an Indian resident in Pakistan. In 2016, Trivedi looked back at this moment and the larger sense of confinement women often undergo through a series of photographs titled Safe Haven. The four self-portraits depict her in poses of longing within the confines of a larger-than-life refrigerator.

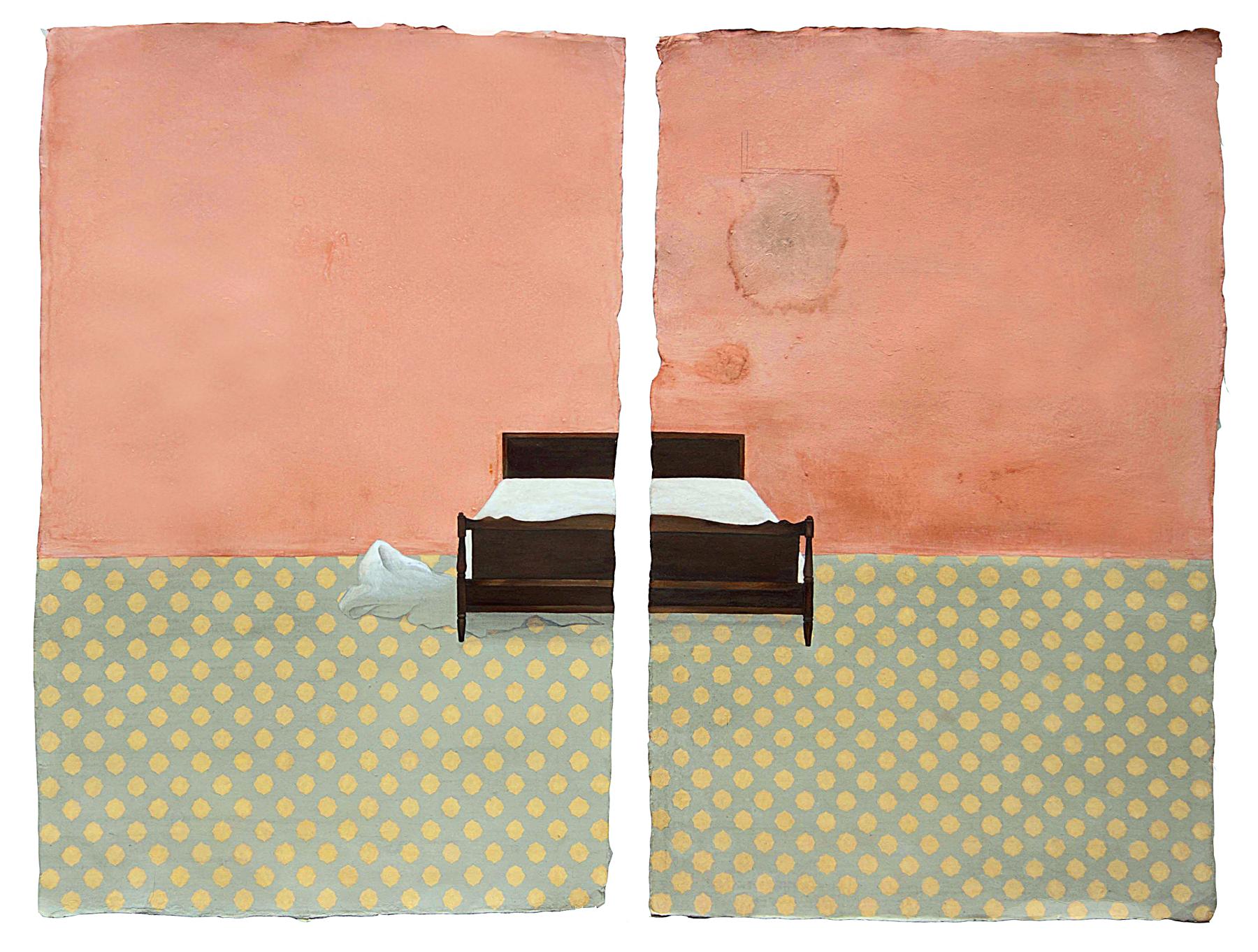

Trivedi is a miniaturist who depicts the daily, domestic and mundane with a sensibility of poetics she inherits from her childhood in Lucknow, India. Her works can be best described as intimate and personal responses to larger social and cultural phenomena that surround her life as a woman. In an untitled painting from the same time Trivedi made Safe Haven, she depicts a bed on a large canvas—there is an imperfect tear in the middle, signalling a breakage of the personal space. A white sheet is in disarray under the bed, which stands against a deceptive peach-coloured backdrop. The work encourages the viewer to ponder about the breakdown of intimate relationships, which often occur behind closed doors.

Untitled (Gopa Trivedi, 2014. Natural pigments, gouache, kadiya and gum arabic on Sanghaneri paper, 45 × 33.5 inches.)

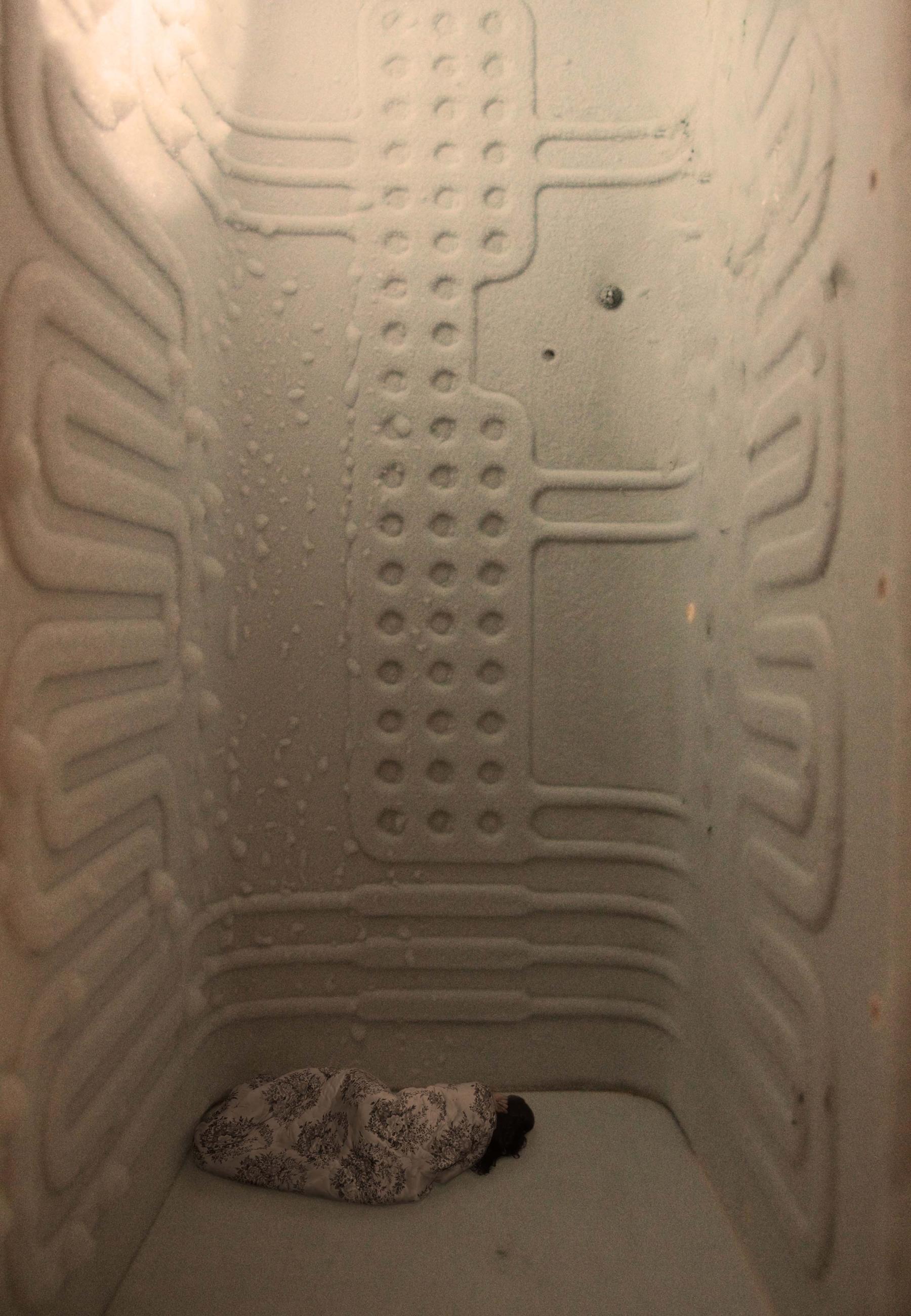

Safe Haven is an extension of Trivedi’s previous work, exploring notions of home, which the artist presents as a state close to solitary confinement in prison, of zero physical or social engagement with the outside world. Home thus becomes a kind of incarceration, which often leads inmates to develop psychological ailments. Trivedi refers to the series as a “safe haven”, a silent nod to the lack of independence she feels in her daily life. This false “safety” women are promised within the “haven” of purity and sanctity that is the domestic sphere is captured by the motif of the refrigerator. It could be read as an enclosed space with multiple layers: a signifier of a kitchen where most women’s domestic labour is done; a space which ensures preservation, much like how women are expected to carry on the lineage of their culture and tradition; a space of discomfort signalled by the fridge-prison’s extreme temperature settings; and a capsule that holds chastity and purity as it does with food items.

Trivedi’s expressionist manifestations in the images raise several points of inquiry. In one photograph from the series, she lies on the floor of the refrigerator wrapped in a blanket, almost ignorant of her outside surroundings as she seeks safety and comfort. In another image, the artist holds a book and stares directly at the camera, as if she finds the equipment to be a mystery that she desires to decode. The camera disrupts her attempts at engaging with the book, which signifies knowledge and education. In the third image, Trivedi looks out of the refrigerator, trying to catch a glimpse of the outside world. Interaction with the outside world, one would assume, would mean navigating the expectations placed on a woman’s bodily autonomy and choices. In an attempt to protect herself from the outside world, Trivedi’s embodied woman retreats into the enclosures of her home, her “haven.”

Trivedi recalls the architecture of her hostel in Lahore, shielding its residents with tall walls, curfews and dress codes. Safe Haven thus renders palpable the surveillance that is foisted onto women, particularly in South Asia, under the garb of ensuring their safety. The photographs are also taken from inside the fridge-prison where Trivedi resides, leading one to speculate if the photographer is a woman too. Trivedi’s documenter, while having access to a camera, has no way of letting her subject out of the enclosed space. The series is exemplary of the role of the artist in commenting on socio-cultural circumstances with nuances from personal experiences. Trivedi’s later works have continued to do this from a feminist perspective that makes the personal the political.

To learn more about artists exploring the gendered nature of domestic spaces, read Sukanya Baskar’s reflections on Riti Sengupta’s series, Things I can’t say out loud (2023), and Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Cheryl Mukherji’s practice from 2021.

To learn more about artists exploring the gendered nature of domestic spaces, read Sukanya Baskar’s reflections on Riti Sengupta’s series, Things I can’t say out loud (2023), and Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Cheryl Mukherji’s practice from 2021.

All Images are from Safe Haven (2014-16) by Gopa Trivdedi unless mentioned otherwise. Images courtesy of the artist.