Documenting the Night: Shahbano Farid On Karachi’s Underground Music Culture

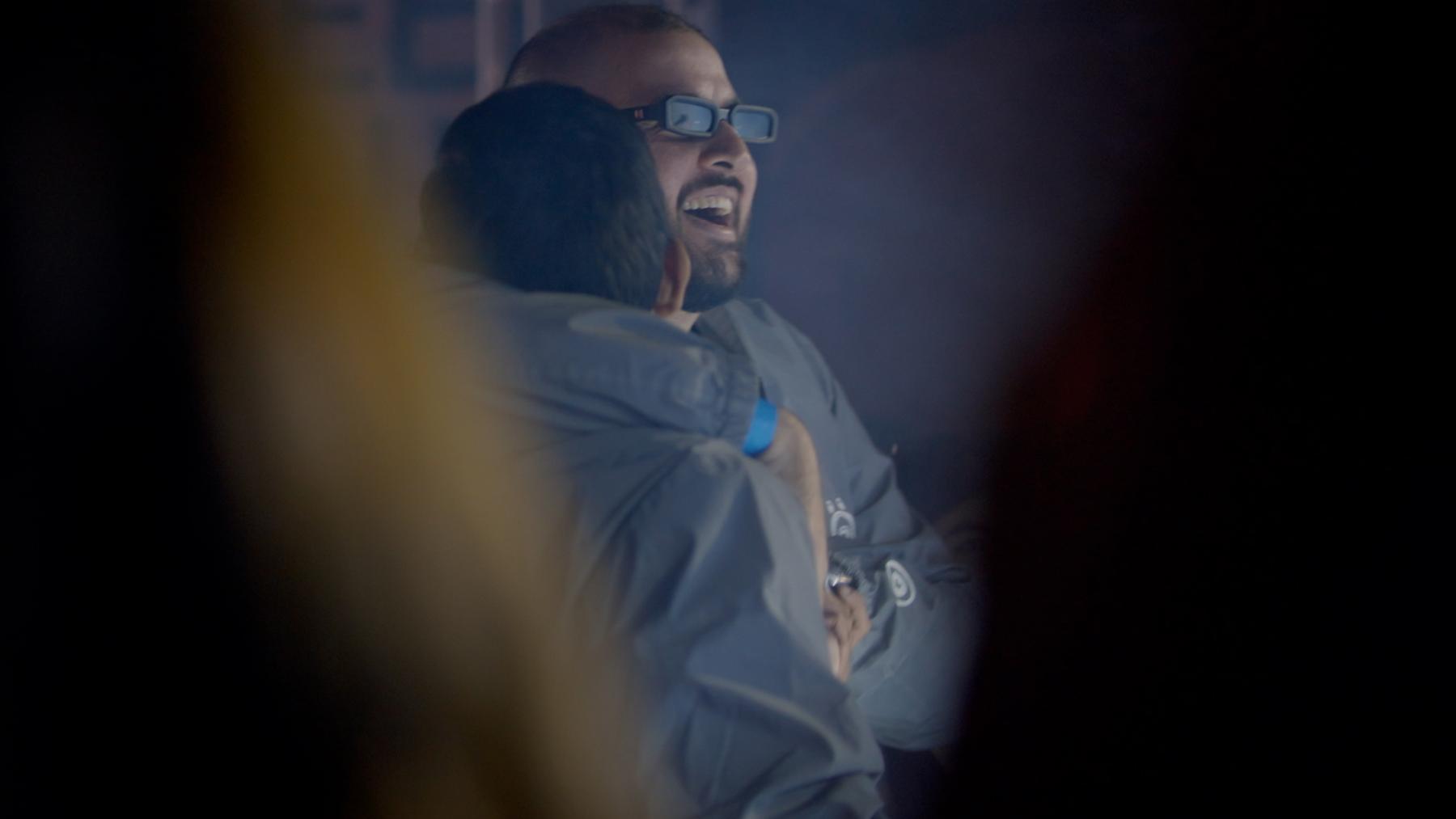

Karachi had a thriving nightlife and music scene in the 1950s and ’60s, which came to an end in the late ’70s with a change of government. Although this period was not as idyllic as it has been recalled to be considering grassroot unrests and protests, it may seem so compared to the later years where there suddenly existed limits on lifestyle. In recent years, there has been a shift as alternative spaces have popped up to celebrate a certain kind of music and community. In her documentary Karachi at Night (2024), Shahbano Farid captures the thriving nightlife scene in Karachi and some of the figures spearheading the movement. In the first part of this edited conversation, she talks about the rise of the nightlife scene and what could have potentially caused it to thrive in recent times.

In this edited conversation, Farid talks about the process of speaking with the artists and the histories of Karachi’s own music scene, which she attempts to capture in the film.

Upasana Das (UD): Through your research and conversations with musicians for the film, what role do you think independent or community-driven radio plays in sustaining underground or independent music culture in Karachi?

Shahbano Farid (SF): Independent or community-driven radio like the Karachi Community Radio (KCR) does a really good job at this. They work within the community to archive music and talent for future generations. KCR is also an audio-visual creative studio, so they do a lot of work with music outside of just the underground realm. They work with some main-stage artists coming out of Karachi and Pakistan. Archival projects like theirs sustain culture. KCR really draws the international community into their DJ sets. Sometimes, for instance, diaspora people coming back to Karachi do a set with KCR, and it becomes a great way to connect Pakistanis around the world. I had the hardest time finding archival footage and photos—maybe that is also due to my lack of access, but I know [such archives are] not readily available.

UD: An essential part of most documentaries is access to the site/community that one wishes to document. What was your process or approach to investigating the underground music scene?

SF: I have a really good friend, who used to live in the United States when I met her, and she just so happened to be from where my family is from in Karachi. So, we ended up hanging out when I was going back and forth from Karachi and we have built our friendship since 2014. She is the one who introduced me to all these people from the scene.

UD: What were some of your motivations to work on a documentary, especially considering your extensive experience in commercial work?

SF: I was making branded documentaries at VICE Studios, and then I did a white label for the Olympic Channel, which was a sports docu-series. I love narrative films, and I would love to make a narrative short at some point, but documentaries are where I feel the most in tune with my craft because there are so many stories to share in this world. I love documentaries and I love everyday people doing really cool stuff. At the time of making Karachi at Night, I was directing for a really awesome magazine, and I loved it, but I was not feeling very fulfilled, unfortunately. I just wanted to make a documentary about something that interested me.

UD: Karachi, and largely Pakistan, had a bustling and active music/nightlife in the 1950s and after, something that has been well documented in memoirs, films and other cultural avenues. How does this particular history inform your approach to Karachi nightlife in 2023? Do you perhaps recall anything your parents or other veterans from the scene might have mentioned about that time?

SF: I do not live in Karachi, so I can only interpret from my experience. We Pakistanis love music. We love dancing, we love going to shaadis (weddings), we love going to mehendis (pre-wedding event involving henna decorations) and so on. It is a huge part of our culture. When you talk about underground, techno, trance, garage, or jungle—those genres are not perceived in the same light. There is a new wave of music that is taking the country by storm, and it is not new right now, but it has been evolving for some time.

If you are thinking of the disco era, of course Nazia Hassan was a huge disco queen and had a massive influence on music. Women were wearing skirts, people were going out dancing—it was a different time. My mother recalls taking the train up to Lahore to go to college, and she would go by herself, with all her friends. It was such a different time and life, and unfortunately, it has disintegrated to some degree.

UD: What was the music scene, and specifically the band scene, like when you were growing up, living outside Karachi?

SF: In the film, there is Orange Noise and Mole. I believe the genres were more psychedelic meth-rock, and then they forayed into electronic music. But you know, there are so many similarities—psychedelic rock is really dreamy, so that is very similar to subgenres of house or trance. I discovered metal music through techno because there is a similar vibration, so a lot of it is connected. That is kind of how they found their way.

You have main stage performances, like film and TV, as well as mass entertainment—dramas are a huge part of this industry. There are concerts and Qawwali nights. This scene is kind of removed from that. A lot of them found music through video games as well. Artists such as The Prodigy and Linkin Park were amongst some of the influences for lots of artists coming up in this generation with many tracks being in the video games they’d play as kids.

In case you missed the first part of this conversation, you can read it here.

To read more about films that document forms of cultural resistance in Pakistan, read Sukanya Deb’s two-part essay on the mujra in Saad Khan’s Showgirls of Pakistan (2020) and Najrin Islam’s review of Saim Sadiq’s Joyland (2022).

All images are stills from Karachi at Night (2024) by Shahbano Farid. Images courtesy of the director.