A City of Sadness: Hou Hsiao-hsien On Post-War Taiwan

A leading figure in the Taiwanese film scene, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s films offer a nuanced representation of Taiwan’s complex, sweeping history. Hsiao-hsien’s films A City of Sadness (1989) and Goodbye South, Goodbye (1996) each grapple with Taiwan’s political upheaval, marked by restrictions on mass media institutions and the freedom of speech and expression; authoritarian censorship; unlawful incarceration; and crushing dissent and voices of people. In a time when majoritarianism is on the rise globally across cultures, it becomes perhaps even more pertinent to read Hsiao-hsien’s films as they traverse a turbulent time in history.

Taiwan has a history of repression; tossed between the hands of multiple tyrannies, the country has never been truly independent. Its modern trysts began with the retreat of the Chinese nationalist party and thereby the Republic of China’s retreat to Taipei in 1949, following Communist Party leader Mao Zedong’s rise to power in the mainland. Taiwan remained under the control of the Republic of China’s president, Chiang Kai-shek, until 1975—a period marked by a conservative and oppressive leadership. The socio-political atmosphere changed in 1987 with the lifting of martial law. In this changing environment, A City of Sadness creates a fissure in Taiwan’s otherwise cautiously sealed history of oppression, bloodshed and dissent. It delves into the themes of identity, loss, expression, resilience, personal and collective experience, and a search for voice and agency in a nation in constant flux.

A City of Sadness is centred around four brothers of the Lin family, each of whom represents different facets of Taiwanese life during Chiang Kai-shek’s rule. The eldest brother, Wen-heung (Chen Sung-young), runs a restaurant and remains largely absent from everyday politics, a reflection of how people were concerned with daily survival rather than the political machinations unfolding around them. The second brother, Wen-sung, never returned from war; The third brother, Wen-leung (Jack Kao), returns mentally unstable from the war, representing enforced disappearance, trauma and displacement during political turmoil. The fourth brother, Wen-ching (Tony Leung Chiu-wai), is a hearing and speech impaired photographer whose deliberate choice to remain detached from political events stands in as a metaphor for the silenced voice in Taiwan’s history. Wen-ching’s love interest, Hinome (Shu-Fen Hsin), a Japanese-Taiwanese woman, adds layers to the cultural complexity of Taiwan. It symbolises the cultural and emotional remnants of Japanese influence over Taiwan.

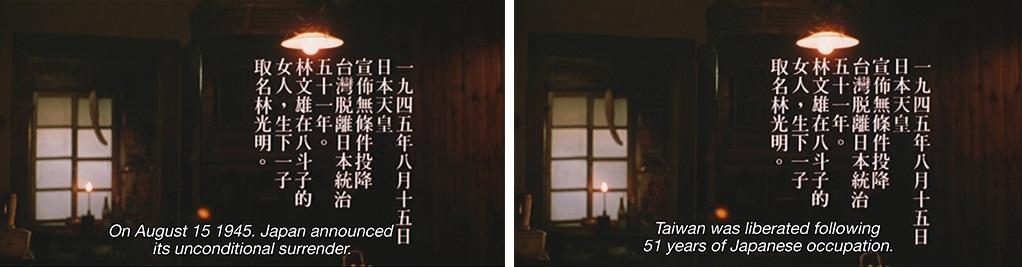

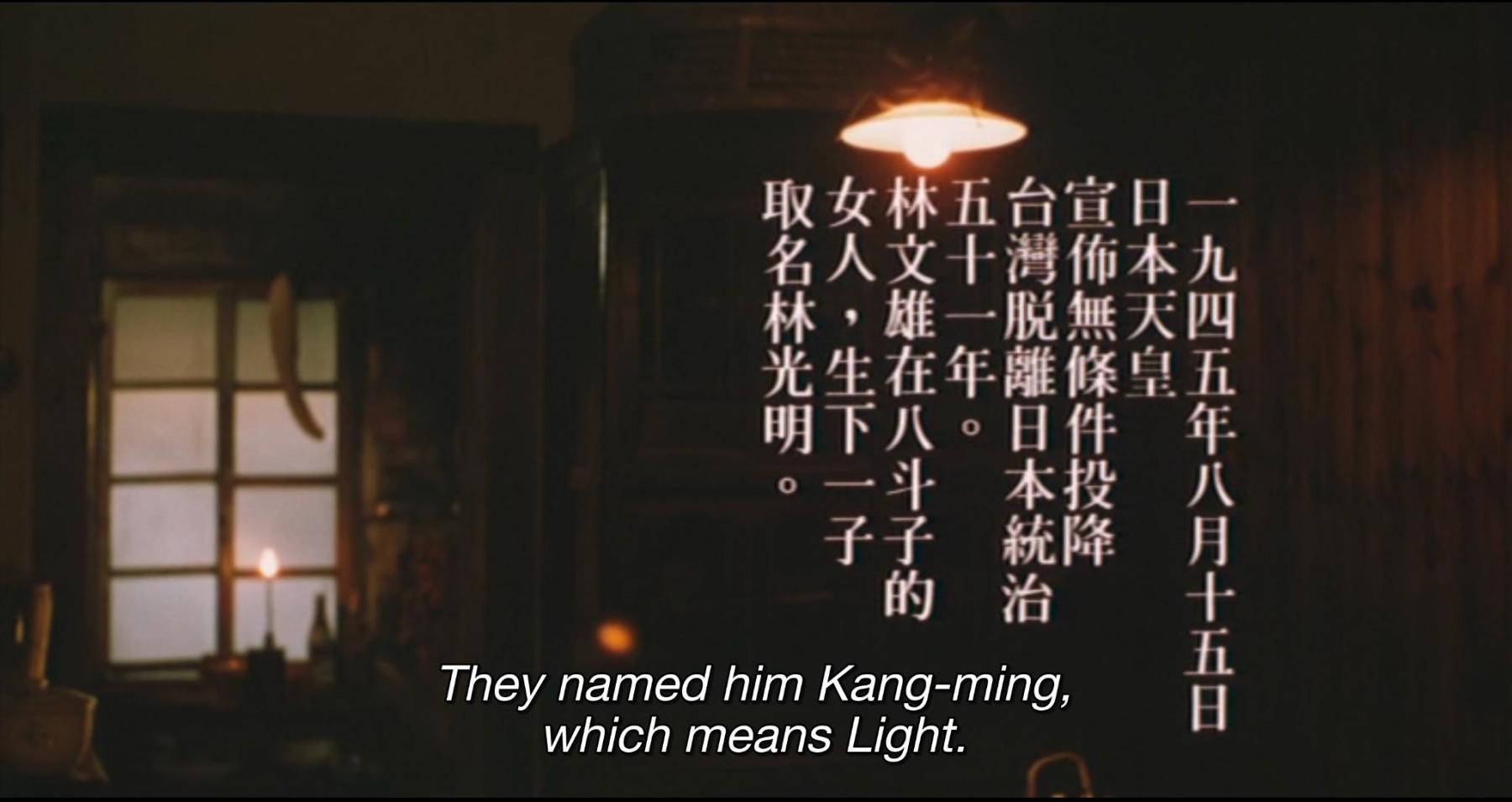

The film opens with an announcement of Japan’s unconditional surrender and the subsequent transfer of Taiwan to the Republic of China, delivered in a solemn voice on the radio by the Japanese emperor Hirohito. The dominant diegetic sound of the radio announcement slowly merges with the agony of a woman giving birth. Amidst a power failure, the father, Wen-heung, walks across the dark room, faintly lit with candles, in anticipation of a child. As the child is born, power gets restored, and the room is illuminated—an overt allusion to the child’s name, Kang-ming, which means “light”. The loud cry of the child symbolically acts as a roaring proclamation of Taiwan’s new birth after fifty-one years of imperial rule by Japan and for Taiwan’s search for its identity amidst the looming crisis and unrest. Here, Kang-ming’s birth is not merely an ironic metaphor for the doomed reunification with mainland China after World War II. Rather, the implicit cutting of the umbilical cord can be seen as Taiwan’s emotionally painful and traumatic severing of its deeply rooted ancestral bond with its motherland.

Taiwan’s status as an independent dominion is woven with complexities. After the authoritarian Kuomintang (KMT), the right-wing nationalist party in mainland China, took hold of the land in 1945, Taiwan was gripped by inflation, with rice prices rising by as much as a hundred times. The frequent incidences of corruption, economic mismanagement and exclusion from political participation during the immediate post-war period led to discontent among the Taiwanese. The brutal killing of a widower on 27 February 1947, by the armed forces for selling contraband cigarettes and political discontent eventually led to the 228 Incident, also known as the February 28 massacre, an anti-government uprising that was violently suppressed by the KMT, which killed thousands of civilians in the rampant bloodbath. Alongside widespread economic failure, the incident became the impetus for the Taiwan Independence Movement.

A City of Sadness renders this event obliquely but conspicuously. Hou incorporates a series of narrative ellipses to subtly connect the apolitical Lin family with this incident, catalysing the unfathomable human catastrophe in the tumultuous and polarising post-war Taiwan. The optimistic tone at the beginning of the film slowly turns towards Taiwan’s bleak future. This contrast serves as an affecting portrait of the impasse generation, whose loss of identity mirrors that of Taiwan. Caught between politics and economic forces since 1949, Taiwanese culture has been the centripetal force wielded by the KMT—a direct way to impart Chinese identity to people. Authoritarian regimes are not created overnight; they are slow and insidious. They systematically erode civil liberties, manipulate legal frameworks and control media, education and culture to spread their ideology and a sense of homogeneous national identity. Thus, anything indigenous to Taiwanese culture was subjected to stringent measures.

In A History of Narrative Film, David Cook writes that Hou’s framing, in some ways like Yasujirō Ozu’s before him, is rather centrifugal in the sense that it destabilises the image and points to a world beyond the shot. Hou’s distant observationalism encompasses the narrative. As Bérénice Reynaud mentions, “…instead of covering the event in broad strokes, Hou staged most of the violence offscreen and worked on a microscopic scale, registering its impact on a particular family.” Thus, Governor Chen Yi’s voice is only heard on radios; soldiers are only briefly shown attacking people, and Wen-ching’s love interest, Hinome, flashes information through notes or voice-overs. Hou conveys wider political events and discourses of the time in short bursts as part of the texture of everyday life as he moves from the general to the individual—from politics to the intricacy of the three brothers’ own lives as Taiwan grapples with KMT rule. These fragmented depictions of events become equally distressing and incomprehensible for the audience as they are for the characters due to one’s inability to know the true extent of situations beyond our control.

After nearly a decade of autocratic rule, KMT slowly relinquished its absolute power over matters and sectors of economic control. As a result, Taiwan saw tremendous growth in the industrial and trade sectors in the 1960s, markedly improving the lives of the average Taiwanese. However, in No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien, James Udden points out that cinema remained one of those industries that missed the “Taiwanese miracle.” Udden further mentions that authoritarian censorship banned the depiction of specific colours like red (“communistic”), yellow (“licentious, pornographic”) and black (“pessimistic views of the undesirable of society”) in 1954 as part of a new policy, “The Culture Cleaning Movement.” Released in 1989, the film presents an antithetical approach to censorship through a profusion of red colours as soon as the opening credits roll on. From the leitmotif of Lin’s family dining room scene, red wall banners, red table cloths, red altar cloths, and red candles dominate the colour palette, almost bursting out of the screen—subtly hinting at the end of a repressive period in Taiwanese film.

In Leitmotif: Persuasive Musical Narration, Stan Link argues that using leitmotif empowers the spectators through cognitive engagement and interpretative agency. It is fundamental to narrative development, has an innate relationship to the past, and registers the passage of time. Leitmotifs are recurring musical themes associated with characters, locations or ideas and have layered subtexts. The film's leitmotif, Hiromi’s Theme, appears twice in the narrative. The theme is melancholic and nostalgic and evokes a sense of sadness and introspection. It carries a subtextual reference to Hinome’s personal struggles within the historical and cultural context she inhabits. Its evocative nature mirrors the film’s exploration of loss, love and the passage of time. The first time it appears is when Hinome goes to work at Kimguishiu Miners’ Hospital and later when Wen-ching tells Hinome about his brother who never returned from war. At this point, the leitmotif acts as a calm and meditative reflection on the peaceful days of ancient Taiwan. Soon, the sound of a flute merges with thrash sounds on an instrument, symbolically suggesting the lives of people in Taiwan grappling with KMT rule. The second time the leitmotif appears is when Hinome’s brother Hinoe (Wou Yi Fang), a progressive intellectual, is beaten by KMT officials after the February 28 incident. The theme shows him returning to his hometown with a dark view of the city landscape amid a glow of yellow street lights, symbolic of the hope that has started to flicker. In both scenes, the visual imagery of the same mountains, with a contrast of upward and downward movements of characters, signals a loss of hope and progress. However, talking about the incident or White Terror under KMT rule was taboo until 1987, when martial law was lifted. With it, A City of Sadness became the first movie to focus on this tumultuous era of Taiwan’s history, reflecting an unfathomable human catastrophe in the polarising post-war Taiwan.

The second part of the essay will examine contemporary Taiwanese youth's disconnectedness from its culture and politics and reflect upon how Hou’s compositional aesthetics render this estrangement through distinct techniques and vocabularies.

To learn more about films that explore film practices that explore histories of repression, read Ankan Kazi’s essay on the rise of short films as alternative cinema in Bangladesh, Najrin Islam’s three-part essay on image politics in Palestinian films and her conversation with Mariam Ghani on Afghan cinema and its archives, as well as Annalisa Mansukhani’s review of Piotr Cieplak’s The Faces We Lost (2017) on the genocide in Rwanda.

All images are stills from A City of Sadness (1989) by Hou Hsiao-hsien, courtesy of the director.