Goodbye South, Goodbye: Taiwanese Youth’s Fractured Identity and Cultural Detachment

The first part of the essay examined Hou Hsiao-hsien's portrayal of social unrest, violence and the suppression of dissent under the Kuomintang (KMT) regime through a microcosmic focus on the Lin family amid the precarious socio-economic landscape of post-war Taiwan. In Goodbye South, Goodbye, Hou’s interest in the ceaseless torment and plight of the Taiwanese at the hands of external forces amidst the relentless struggle for Taiwan’s own history and national identity continues. Through the film, Hou aims to discern the contemporary Taiwanese youth's alienation from its politics and culture. The decades of oppressive rule resulted in silent despair and hostility towards politics; as James Udden mentions in No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien, for many native Taiwanese, “getting involved in politics is like eating dog shit.”

In the film, Hou presents low-life characters navigating the rural outskirts of Taiwan. As a mash-up of scenes that can be arranged differently without affecting the overall narrative or experience, it alternates between stasis and movement. Hou’s compositional methods are frequently paralleled to those of Japanese master Yasujirō Ozu, who is considered the progenitor of modern “time-image.” According to Charles Warner in Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Optics of Ephemerality, “…time-image gives rise to purely optical and sound situations that refuse to be extended into action.” Like Ozu, Hou tries to freeze time and convey to the viewer the fleeting nature of each moment. However, unlike Ozu, Hou edits at a dissonant speed, allowing the moment to flow rather than coercing it into plot functions. Thus, when watched in isolation, each scene has a philosophical bearing on the passing of time and a zen reflection on Hou’s aesthetic of showing otherwise usual characters. Hou transcends the mundanity of everyday life, set against a backdrop of socio-political and historical aspects of Taiwan, with his philosophical and numinous gaze. According to director Jia Zhangke, Hou’s disciple, the long takes instill “a sense of deadlock.” You feel the passage of minutes and the weight of life keenly as it presses down, as nothing significant happens in the scene.

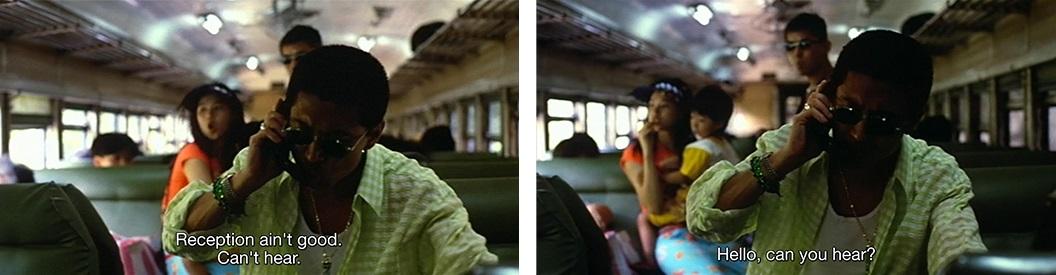

The film begins with credits on a black screen and gradually introduces a piece of rock music, Self Destruction. The music is from the album of Lim Giong, who also plays Flathead in the film, a Taiwanese musician, DJ, actor and an active figure in the Taiwanese experimental electronic music scene known for Hokkien rock songs. With the sound of a moving train, the frame dimly lights up, and the brothers Gao (Jack Kao) and Flathead (Lim Giong) and his girlfriend Pretzel (Annie Yi) can be seen in the middle of the frame inside a train. With his dark sunglasses and phone on ear, Gao makes for a fascinating figure, with the air of a dealmaker. However, as soon as he loses cell phone reception, the facade collapses, and Gao ends the connection by shouting into the handset, straining to hear the other party. The scene constantly alternates between shadows and light.

In Hou’s films, framing is minimal. He sets his frames in a mode of chiaroscuro, unlike the high-contrast expressionism of noir, which lends space porosity rather than depth of field. According to American film theorist David Bordwell in Figures Traced in Light, “Hou bathes most of his scenes in darkness” and obscures the most significant details in the film by staging them near or outside the frame’s borders, which, in a certain sense, metamorphoses after they slide beyond the frame. In On Four Prosaic Formulas Which Might Summarize Hou’s Poetics, Fergus Daly states that Hou calls his frames, ‘zones’, “which may have some empty shots, but that is an error; the shot continues to contain affects, floating in space.” He compares it to Chinese prints, in which empty spaces have an ulterior motive of transporting the gaze to make spectators encompass whatever is effectively represented. The empty spaces influence the perception of spectators and, with their profound philosophical bearings, complement what remains invisible as much as it does for the visible.

The previous scene with Gao, Flathead and Pretzel cuts to an exterior shot of trains crossing each other against a backdrop of mountains. Unlike the usual fade, the song abruptly stops soliciting the spectator towards a calm, serene moment of reflection. The trains seem to drift away in the opposite direction from the characters’ lives, with no sense of permanence or hope to arrive at the juncture that will transport their lives for the better; for Flathead, it would have been shifting to the USA, and for Gao, to open a restaurant in Shanghai. The scene’s unexpected cut to strange angles and puzzling perspectives reveals the multifariousness of human experience. Hou’s long takes do not capture time spent as much as time wasted. He makes us aware of the temporal representation amid the fleeting reality of his characters’ existence and the only consolation that time can bring to their lives—wisdom.

Fergus Daly expands on Hou’s aesthetics, which makes his characters distantly removed from the actuality of which they are a part, further engulfing a sense of strangeness between the characters and the audience. Throughout the film, Hou’s signature long takes and his fondness for gliding dolly shots convey the brothers’ aimlessness and insularity, including stunning views from the front and back of moving trains, motorcycling through the lush forest, and the city as seen through the green-tinted windshield of a car. Their indifferent detachment from the world is a microcosm of contemporary Taiwanese youth’s disconnect from their social and cultural roots. The title of the film, Goodbye South Goodbye, suggests departure; the beginning is predicated on the forward motion of motorbikes, cars and trains, only to end in a ditch on the side of the road in the middle of nowhere. The departure mirrors Taiwanese youth's alienation and hopelessness caught between Taiwanese culture and Western modernity in the course of Taiwan’s rapid economic change as they navigate an environment that holds no certainty for their future.

Taiwanese youth's estrangement from their social and cultural roots is also a consequence of the language division fostered by decades of foreign occupation. Language is an integral marker of territorial space and culture, and Hou’s cinema reflects this sense of separateness experienced by the Taiwanese. The pioneers of the Taiwanese New Wave, most notably Edward Yang and Hou Hsiao-hsien, reintroduced Taiwan’s indigenous dialect in their films. Through socially conscious and artistic films, they ended Taiwan’s repressive, controlled cinema history, where no film outside the Chinese-speaking world gained recognition. They brought to the forefront the complex and tumultuous period of Taiwan’s history: severance from China, a search for inclusion and its own cultural identity, and a congealed period of violence and suppression such as watershed events like the February 28 massacre that were often not discussed or emotionally accepted. In this history of Taiwanese cinema’s outreach and critical acclamation, Hou Hsiao-hsien plays an indispensable part.

In case you missed reading the first part of the essay on Hou Hsiao-hsien’s A City of Sadness (1989), you can read it here.

To learn more about films that explore the dreams of youth, read Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Achal Mishra’s Dhuin (2022) and Jigisha Bhattacharya’s review of Franz Böhm’s Dear Future Children (2021).

All images are stills from Goodbye South, Goodbye (1996) by Hou Hsiao-Hsien, courtesy of the director.