Engaging with the Surface: Materiality, Memories and the Digital in Sheetal Mallar’s Braided

The family album, by the very act of collective viewing, reaffirms the significance of the bonds between the viewers. By traversing the decades that have led up to the present moment together, family members as individuals gain subjective perspectives into their own life journeys. But what about an album of images not meant to be collectively viewed in family settings? When the traditional structures of the ‘family’ itself have been abandoned, what does the contemporary ‘family’ album look like?

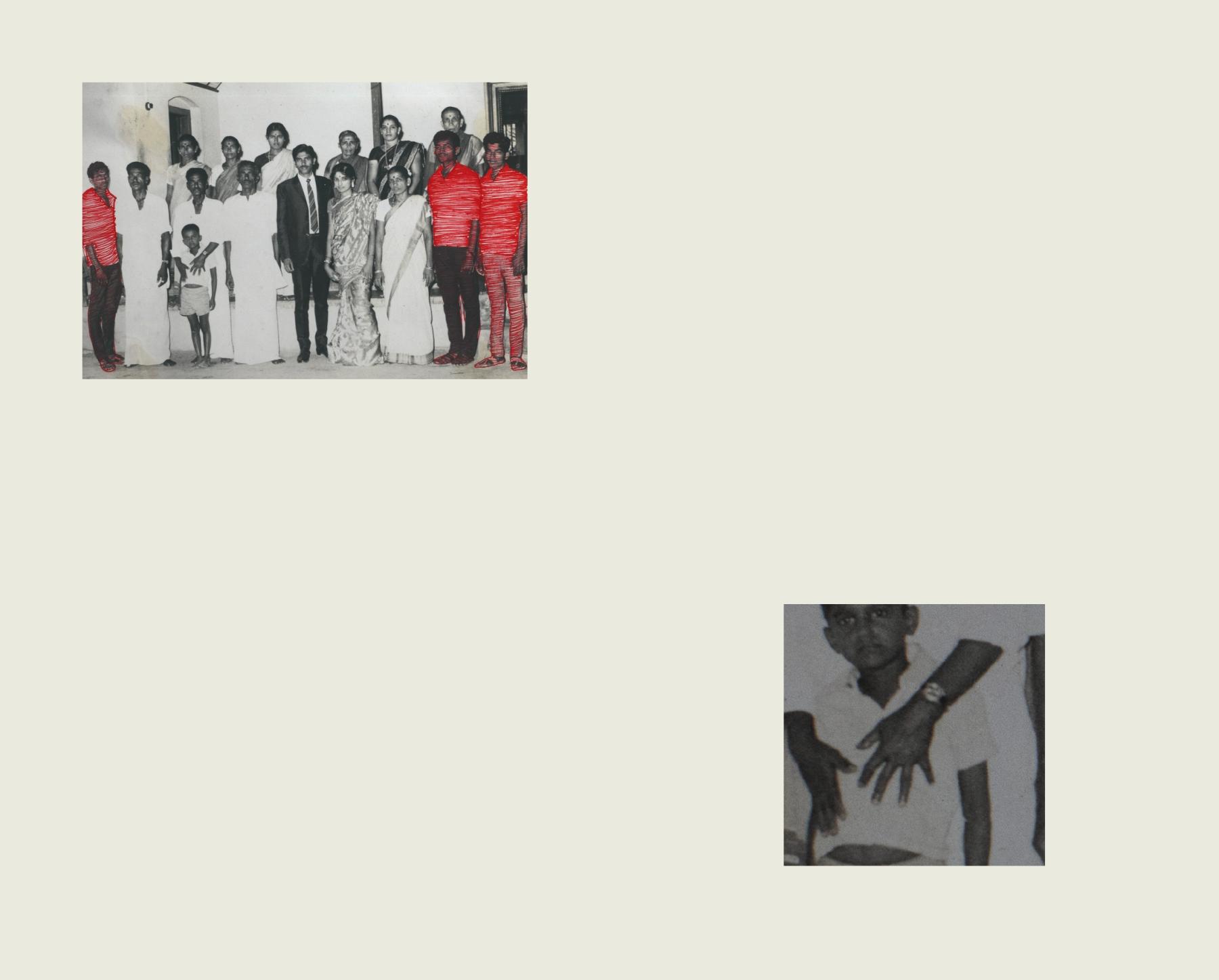

Sheetal Mallar’s series, Braided (2023), grapples with these questions in the format of the printed photobook. Unlike the collective viewing of the family album, the journey through Braided is completely solitary, reflective of the isolated lives in the digital age. Except for the sparse text inserted after the images, there are no overarching textual narratives. Thus, the images retain a certain autonomy of narrative within themselves, independent of textual dictates. In many ways, Braided encourages the viewer to become the narrator, interweaving the images into personal encounters. This signals towards two developments—the family album as a medium of choice for the artist and the emergence of braiding as a language within that format. What I imply by the latter is Mallar’s intervention in the traditional album format by deliberately focusing on photographs of the women in her family (her mother and maternal grandmother, Amma). Braided channels a secretive, inner conversation between the women in the family. From the red coloured threads binding the photobook to the thematic red scribbles, wherein Mallar exercises the agency to choose who and what to remember in the family group photograph, braiding is a constant strategy to conceptualise an intergenerational female lineage. It is also this approach that allows the photobook to embody diverse material histories.

An older group photograph has been digitally scribbled with red lines on selected male figures. Below, a section from the same photo has been cropped and re-printed, which would be visible through the frame cut-out when the sheet is folded.

What follows is an exploration of Sheetal Mallar’s Braided as an embodied viewer, following Geoffrey Batchen, who states in his book Forget Me Not: Remembrance and Forgetting (2004), “… when we do touch an album and turn its pages, we put the photograph in motion, literally in an arc through space and metaphorically in a sequential narrative.” The element of touch cannot be divorced from observations around the photobook, which invites the viewers to not just look but also engage with its materiality in multisensorial ways. This differs from the interaction with the traditional family album as the haptic dimension is, in most cases, ruled out as finger prints cause permanent damage to the photographic surface. Moreover, as Elizabeth Edwards argues in Photographs Objects Histories (2004), “Material forms create very different embodied experiences of images and very different affective tones or theatres of consumption.”

With the proliferation of digital image-making and viewing, the very materiality of images has come under intense scrutiny. Is the digital immaterial and therefore ahistorical? What happens when the analogue photograph is digitally scanned and printed as an image? In Mallar’s book, a spread presents two photographs torn in half, digitally scanned and staged alongside each other. A preliminary first glance would give the impression that they are not just prints, but actual photographs that were torn and pasted on paper. By invoking nostalgia of the past with tools of the present, from the sepia-toned photographs to the exaggerated tear marks scanned and placed together, the design of Mallar’s photobook weaves multiple materialities and temporalities within the format of the book.

Photographic portraits of Mallar’s mother and Amma, digitally scanned and printed.

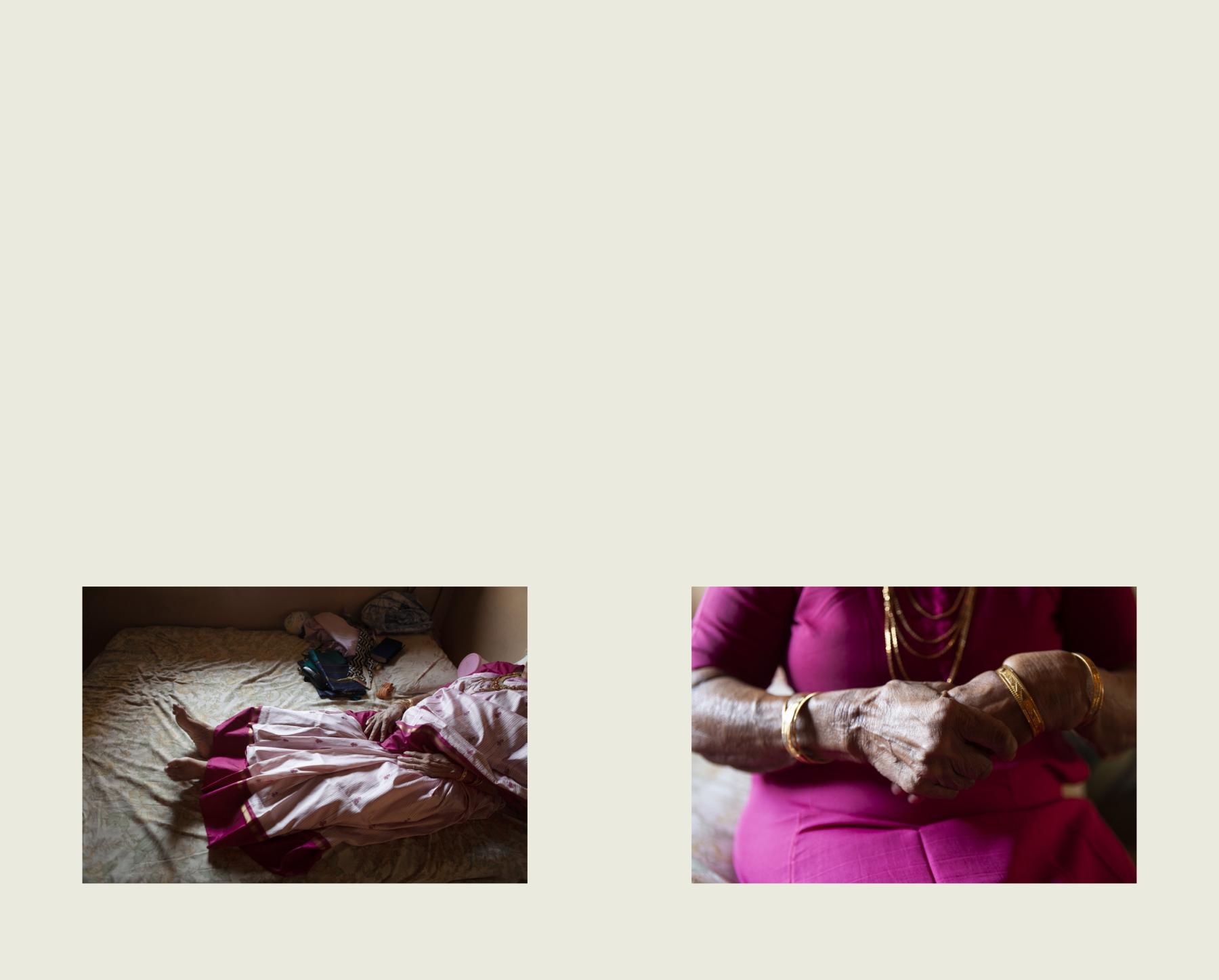

In many ways, Braided is an exploration of the afterlife of the family album, in the form of the photobook in the digital age. Along with the horizontal format reminiscent of the family album, the photobook also incorporates unconventional portraiture with an intense focus on the aging female body. It includes closeups of feet, the body draped in a saree and bangled hands. The artist also documents the process of getting ready before taking the image. The decision to include such images in the photobook, which would have otherwise been discarded in the family album, is also noteworthy in the choice of subject matter for memorialisation.

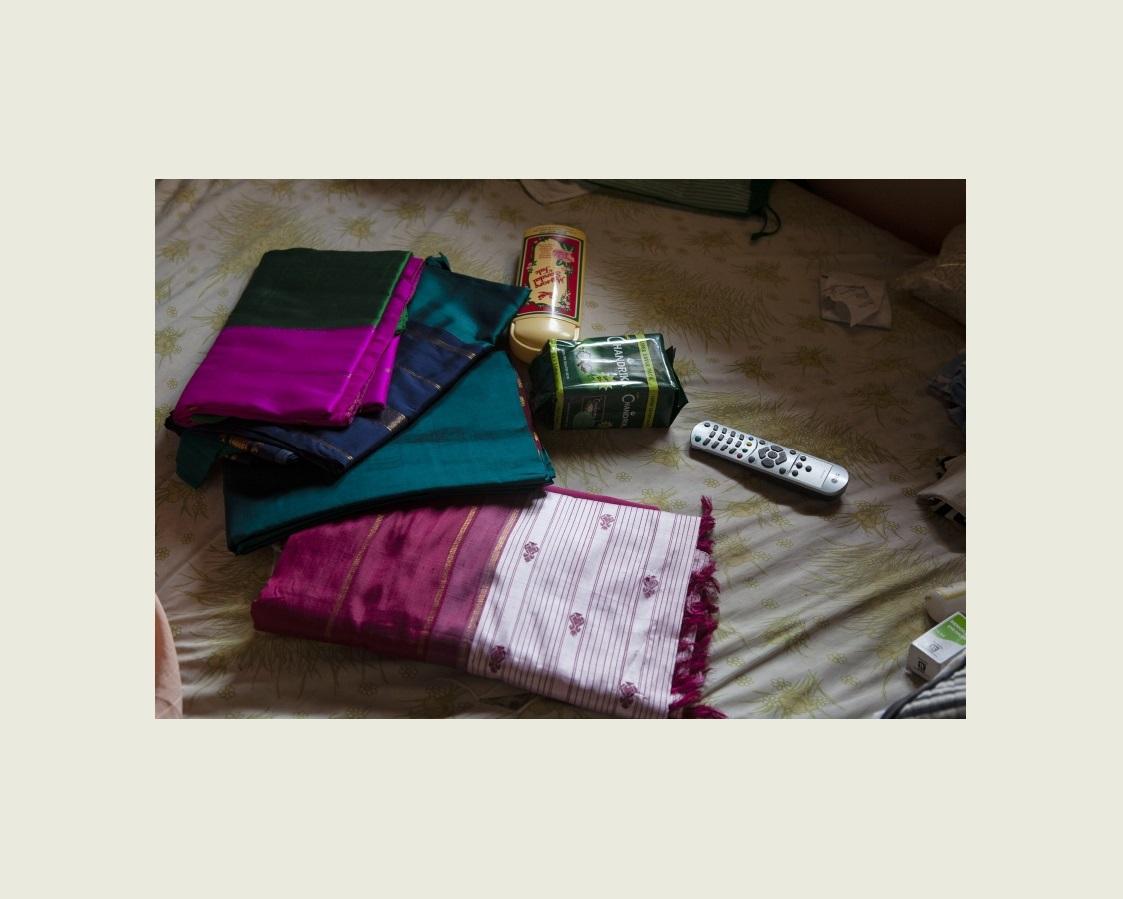

Braided speaks volumes about the profound potentialities of remembrance embedded in objects of everyday use. Such objects outlive their users, bearing their material traces long after they have passed away. If one looks at the strategies Mallar employs to visualise an intimate portrait of her Amma, specific objects emerge as protagonists and narrators—the TV remote, piles of clothes, toiletries, the red comb, etc. The fact that these everyday objects are linked to women’s lives within the home brings us to the role of women in memory-making. Apart from digitally scanning, editing and inserting photographs from her family album, pre-photographic memorialisation practices in the form of embroidery, painting, letters and, especially, hair are referred to in Braided through various digital tools. This evokes not just a complex web of temporalities, but also the historical role of women as the family archivists. The history of the domestic, private sphere has for centuries been archived and memorialised by women.

Amma’s portraiture with a close-up of her hands and feet.

Documenting the process of getting ready.

What we view in Braided is not just a documentation of family history, but also a curation of the landscapes of memory and grief through digital image-making. The entire journey through the photobook is bold, intimate and intensely sensual—fingers engaging with the surface while traversing the materiality of the past in the digital present. Furthermore, Mallar embarks on pulling out certain photographs from the family album, digitally scanning and editing them, to subsequently inserting them in a photobook that will be mass reproduced. This has myriad implications: of not just historical visibility but also economic viability. For the longest time, women’s labour—creative or otherwise—went unrecognised beyond the domestic sphere.

Before the advent of photography, the only tangible memories of a female ancestor might be a piece of embroidered fabric, or—in very few cases—an occasional handwritten letter. But with the gradual dissemination of photography in the private realm, women became the primary keepers of tangible memory in the form of family albums. However, none of this was mechanically reproducible or exposed to the market. Thus, prior to the proliferation of social media and digital visual cultures, the tangible creative labour of ordinary women stayed within closed doors, unseen by the public. With the rise of an object like the photobook, which is inherently reproducible and made for the market with an intention to generate capital, the importance as well as the influence of domestic histories have been substantially altered. Moreover, with the rise of social media networks, every entity—from a photobook to a human being—has a distributed, even diffused presence over multiple online sites. Braided is no different, and Sheetal Mallar’s decision to reproduce this particular intimate world signals a new age where personal histories proliferate in uncountable ways.

To learn more about artists who have explored the gendered dimensions of family dynamics and personal histories, read Sukanya Baskar’s reflections on Riti Sengupta’s Things I can’t say out loud (2020–Ongoing), Sukanya Deb’s essay and curated album from the Feminist Memory Project by the Nepal Picture Library, as well as Shranup Tandukar’s observations on Prasuna Dongol’s Before You Were My Mother (2022). Also read Anisha Baid’s essay on Geoffrey Batchen’s concept of vernacular photographies.

All images are scans from the photobook Braided (2023) by Sheetal Mallar. Images courtesy of the artist.