A Tripod Made of Stone: Interview with CAMP’s Shaina Anand and Ashok Sukumaran

In this edited conversation with Shweta Kishore, Shaina Anand and Ashok Sukumaran speak about the inception of CAMP as an artistic collective and their continuing focus on decentering relations of being, seeing and being seen. Anand and Sukumaran discuss how developing site-specific methodologies, including unusual combinations of media technology and materials, as well as collaboration with human and non-human entities, is central to their media art practice. Their interests lie in the experimental repurposing of analogue and digital technologies such as CCTV, computers, servers, video recorders and switchers. They work with infrastructures, archives, documents and objects to create art that puts into question our understanding of materials, structures, media and art itself. At the same time, engaging the collective in both production and exhibition, projects re-map the boundaries between art, social and lived space. Located in spaces of popular habitation such as neighbourhoods, streets, docks, terraces and markets, their artworks comment on the institutional ‘placing’ of art and its relations with spaces of production and consumption. In this conversation, we explore these topics and CAMP’s core belief in re-working the relations between author-subject-technology and regimes of visibility and invisibility, thus enticing us towards a political form of seeing and sensing.

Shweta Kishore (SK): How do you define your media practice and how is it related to your artistic and professional backgrounds?

Shaina Anand (SA): CAMP came together in 2007. We all came from very distinct and diverse practices that were not necessarily within the ambit of ’Fine Arts’. Ashok had studied architecture and media arts, while I had studied film and history. And Sanjay (Bhangar), who co-founded CAMP with us, was involved in Indymedia and software programming.

When we set up CAMP, we made a statement of what it is that we wanted CAMP to be. There was a conscious effort to not define ourselves as a ‘collective’, but rather as a space of a forcefield of conditions, materials and actions that would allow us “to think and to build what is possible, equitable and interesting for the future.” As we turn seventeen this year, it is nice to look back and know that we stuck to our raison d'etre; the about page on studio.camp remains unchanged since 2007.

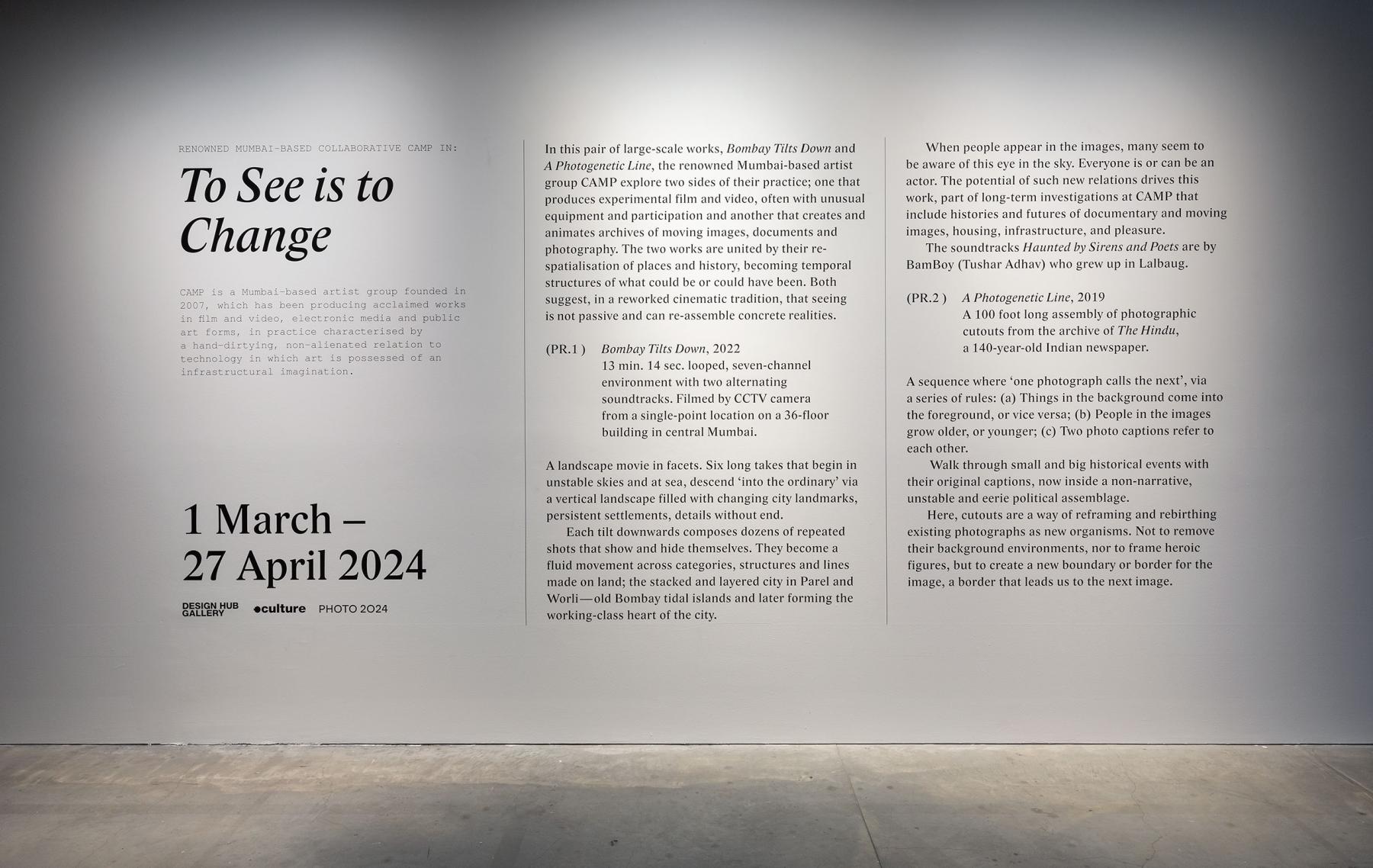

Installation view, CAMP, To See is to Change, Exhibition Text, Design Hub Gallery, Melbourne, 2024.

SK: Can you talk more about CAMP’s early approaches?

Ashok Sukumaran (AS): We took a complicated route—trying to frame the relationship of early twenty-first century media to a specific situation. In an early project, I worked with electricians and street decorators in Bombay to create patterns of movement on the street—theirs were highly evolved ways of accessing public space and using moving images and animation.

SA: I came to it with a clear critique of documentary filmmaking practices as they existed in the mid-1990s in our region. Within the history of cinema and documentary film, there have been many moments where images were ruptured, boldly assembled, materially tweaked—everything passing through the strip of film and the world around it taken apart or critiqued. The figure of the independent documentary filmmaker in early 2000s India was different from that of the previous decade. You could have your own camera and your own editing machine! There was joy and liberation in owning a second-hand mini-DV camera and in taking your own images. But then I would sit back down and think, “Damn, I have thought so much about this, and I have also complained about what I can do to change the image. What is that missing image? Where can it come from? What can be cinema by other means?” Those questions began our experimentation.

We were using everyday technology that was around us to make art. Those early proto-CAMP projects were electrical and distributive experiments. We worked on the ground with terrestrial networks. Switches and hand cranks appeared on promenades and city squares, where people could send lights and signals, or even share electricity. TV sets with CCTV grids in neighbourhoods where people could performatively communicate, TV channels inside markets. Members of the public inside CCTV control rooms, or performing under city cameras. There are several ways to describe what we were doing: interventions, performances, dialogical art, interactive art, public art, happenings, new documentary, all of the above? It was not very clear what it was.

Installation view, Photographic Line, 2019. CAMP, To See is to Change, Design Hub Gallery, Melbourne, 2024.

SK: Talking about the use of found footage and CCTV, your methodology is not only about creating an artefact, but it has a social energy to it. Tell us what your process of gathering materials and images looks like.

AS: (Words like) ‘found’ have become very neutral for us. It is an uncomfortable word, and we have always found it strange because it reminds you of the art historical ‘found object’. But our (method) is very different; you are seeking it out. There is a politics to it.

SA: When we built our own pop-up infrastructure for CCTV in Jerusalem in 2009 (for The Neighbour Before The House), it was 100% guerrilla filmmaking. You are not going via the Israeli state or asking the city police for permission to film on the streets and at monuments. You are doing all of it with a cheap CCTV camera, cables and mics, with the support of a network of comrades and subjects. In this case, the subjects became the ones taking the shots.

Installation view, Bombay Tilts Down, 2022. CAMP, To See is to Change, Design Hub Gallery, Melbourne, 2024.

AS: The method is like a triangle; the subject is behind the camera and the camera is fixed to a building. A friend described it as a tripod made of stone. The author is somewhere on the side, provoking all this. We used this approach in Bombay Tilts Down (2022) as well.

SK: Technology is often assumed to be transparent—for example, the role of the camera, who has the power to operate it, or what its limits are and how that shapes what is filmed, is often concealed in the artefact. In the context of Bombay Tilts Down, the technology is not transparent. Can you speak about this aspect of technology in your work?

AS: The whole point is to show the non-transparency of media. We are using a device and a set of methods, and sometimes we reveal that, so you know you are not watching a (scripted) narrative. We allow this idea of “falling from the sky” to tell you what a generic CCTV camera can do these days if it is not just waiting for an event. Our camera starts to scan or move on its own and thus becomes much more powerful. A “patrolling” feature built into the surveillance mechanism allows us to continuously explore the vertical landscape and therefore a hierarchy within the city.

People who live in apartment blocks, even if living in pretty bad conditions, have great interest in investing in CCTV equipment. They are willing to invest large amounts of money in this system, which ends up being used for all kinds of things—from tracking people's children to spreading stories and playing out social rivalries. There is a fascination around it.

Installation view, Bombay Tilts Down, 2022. CAMP, To See is to Change, Design Hub Gallery, Melbourne, 2024.

SK: Could you talk more about the location and the local histories that you were engaging with?

SA: The camera was mounted on a pole fixed to existing window-cleaning infrastructure atop a well-known hotel. Everything you see across the six screens is the west side view from Central Mumbai. You can see Hornby Vellard, a colonial-era causeway linking Worli to Bombay Island and Colaba, eventually uniting all seven estuarial “islands” of Bombay. In the ocean is a one-of-its-kind in the world and one of Bombay's oldest monuments, the fifteenth-century dargah (shrine) of Haji Ali of Samarkand. The dargah has its own legend—Ali did not want to plunder the earth, so he requested not to be buried on land and instead to be cast out at sea. The Hornby Vellard was built 250 years ago and now the coastal road is being built on top of it, literally swallowing the Haji Ali Dargah.

When the film starts, you can see offshore oil rigs and the Prongs lighthouse, which is 15 kilometres away from this camera, because of its range. You can see the horizon of the open sea and the large shipping containers in the distance. You see the trawlers and the larger fishing boats of certain influential Koli communities, but also the smaller ones in their chappus (row boats) with bag nets. You see the (construction) cranes, the birds in thermal, and the tall buildings: old wealth and new. You sense the future, as the storms come in. Then, each screen zeros into a particular building and begins to drop and take a longitudinal scan of the environment, till it reaches the ground some kilometres later. Several “single shots” or “long takes” were filmed from that single point over months. Distance is flattened as the camera tilts down, creating a painting-like flatness. The shots subtly dissolve and fade into footage from another time. It is like you are painting over the image with these downward strokes. Another day comes, and another character appears and looks at you.

Installation view, Bombay Tilts Down, 2022. CAMP, To See is to Change, Design Hub Gallery, Melbourne, 2024.

AS: Cosmopolitan Bombay is being violently chopped up into these property lots, which are being watched over by cameras. There is that level of everyday violence.

SA: That violence is structural. Masao Adachi wrote about landscape theory, or what he called Fūkei-Ron, where he states that to understand power, you must understand geography and the landscape.

To learn more about CAMP, read Ankan Kazi’s essays on Bombay Tilts Down (2022) and The Neighbour Before the House (2009–11), as well as Gulmehar Dhillon’s reflections on A Photogenetic Line (2019).

All images courtesy of CAMP. Images by Christian Capurro.