To Film a City: In Conversation with Shaina Anand and Ashok Sukumaran

In this continuing conversation with Shweta Kishore, Shaina Anand and Ashok Sukumaran from the artistic collective CAMP discuss their engagement with documentary cultures, the use of soundscapes and the construction of a new kind of spectatorship. They speak about the projects Bombay Tilts Down (2022) and A Photogenetic Line (2019) as well as the confluence of local histories and city cultures with the image-making of documentary and surveillance.

Shweta Kishore (SK): In Bombay Tilts Down, you use protest music and people’s poetry that is closely connected to the history of Bombay and its working-class cultures. How does the audio fit in with the visuals? A lot of alternate discourses around class and urban development are often silenced. Is that something you were thinking about?

Shaina Anand (SA): We have two alternating soundtracks. There is an ambient, quieter one where the landscape speaks to you first. Then there is the airwaves one, where we are not saying whether the sound is emerging from down or up. It is travelling, “on air”. A lot of the recordings are of dead poets, balladeers and singers, but their voices can be heard today because they were recorded. We bring an archive alive.

The “standing on shoulders” and passing the baton that we do in our archival practice continues in the soundtrack for Bombay Tilts Down with the inclusion of lok shayars (people’s poets), singers and a new generation of artists like Bamboy, who did the music for our film. He grew up in Parel, near where the camera is located.

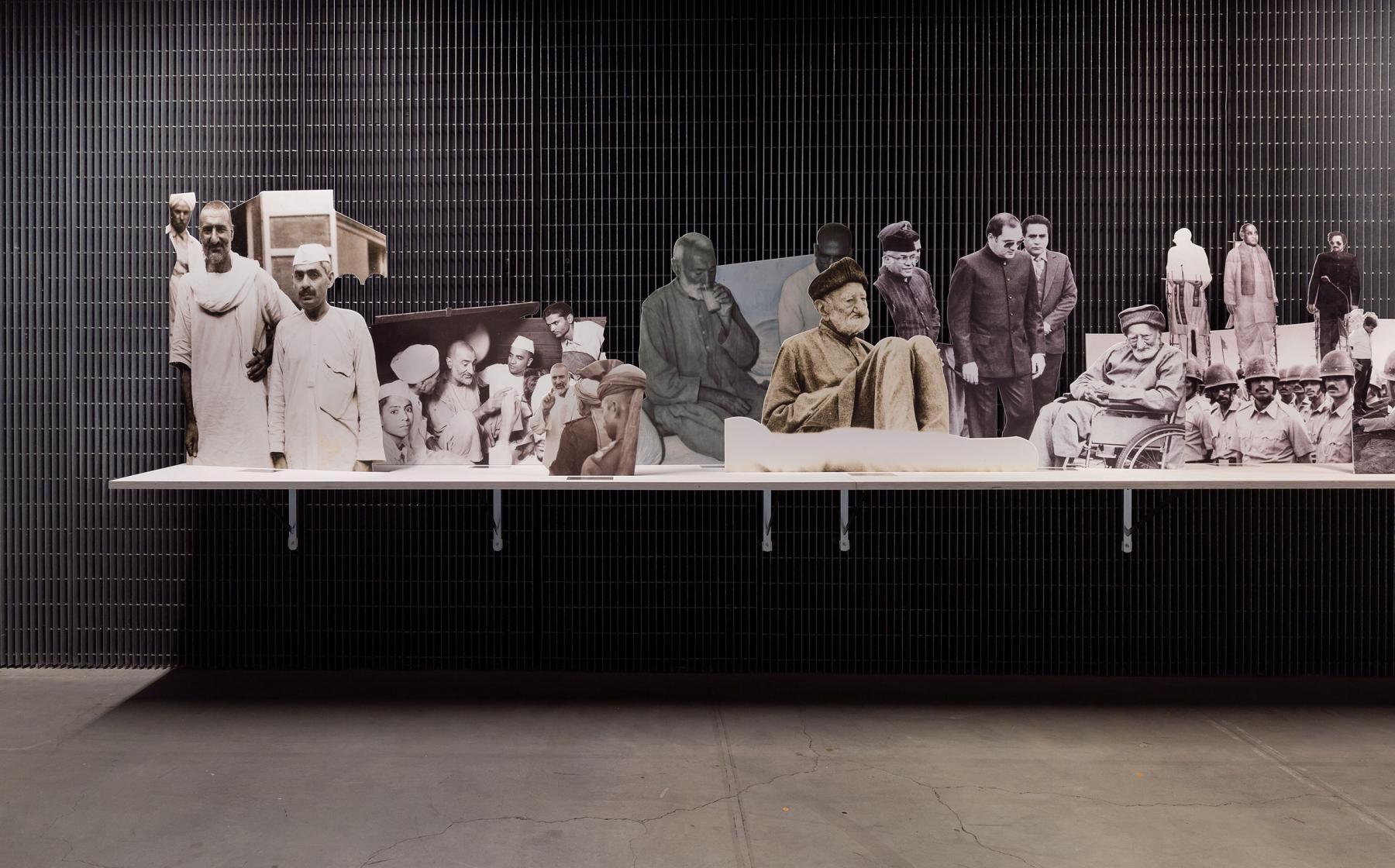

Installation view, Photographic Line, 2019. CAMP, To See is to Change, Design Hub Gallery, Melbourne, 2024.

SK: How do you approach spectatorship in the gallery, given the scale and architecture of the work? Is there a different experience compared to the cinema theatre?

SA: The audience needs at least three or four loops to really get a sense of the details. Bombay Tilts Down is shown in a wide accordion because it is composed of these longitudes stuck together. People watch one or two of the loops standing back and are overwhelmed by the scale and choreography of it as a landscape. But the folds and breaks defy the landscape, panorama or the “immersive experience.” You are invited closer in to see a single screen, or a diptych, and then move on to the lyric video, and then get even closer to the screen. As you go closer, more details become visible. It is as if each tilt down is its own film, with its own geographical narrative.

What we are seeing are very dense and loaded histories. The question “Whose land is it?” undergirds the work. How deep the audience wants to go and what they want to take from this differs. The community sees it differently, the city-goers will see it differently and the housing rights activists will see it differently. The work is undoubtedly monumental, but then you can flip it around and say it is a kind of Arte Povera. It is one CCTV camera on a roof. It has been filmed pretty much on a zero budget during the pandemic by squatting on the roof of a hotel that boasts of its view. In that sense, it is extremely minimal, even though once it is set up, it resembles an Isaac Julien type of production.

Installation view, Bombay Tilts Down, 2022. CAMP, To See is to Change, Design Hub Gallery, Melbourne, 2024.

SK: We were talking about open archives as something that is not in the past or dead. I want to connect this idea with A Photogenetic Line. It makes visible other histories when images are detached from the logic of information. How is A Photogenetic Line connected to your interest in animating archives?

SA: In many ways, A Photogenetic Line draws from the archival websites Pad.ma and Indiancine.ma. Pad.ma features densely annotated listings that you can search and arrange by time code. These edits and affinities appear at first when you search text in the archive. Rules for montaging, which evoke assemblage or montage theory or even early AI, have been used in A Photogenetic Line.

Ashok Sukumaran (AS): A Photogenic Line is a linear 100-minute or 10-minute film, in which one image calls to the next. There are rules for aging people and similar words in photo captions themselves: what the image says, what the photo caption says and what is happening to time within the image. Montage-like rules that connect one image to the other.

Installation view, Photographic Line, 2019. CAMP, To See is to Change, Design Hub Gallery, Melbourne, 2024.

SK: Tell us about your experience as artists within the context of the contemporary move to decolonise art institutions. Have you experienced a different approach towards art from the Global South? Is there deeper critical engagement with this art?

SA: We chose to enter CCTV control rooms in the UK in 2008. This is a privilege given to us by way of art, and for me, this, for example, was a more generous gesture than making art from a brown colonial female subject position in a country that colonised my nation. Instead, the brown colonial female subject opens up the CCTV control room to members of the public. Similarly, I am privileged to have evening soirees in the markets of Senegal in 2008, with battery-powered screenings discussing Djibril Diop Mambéty, Ousmane Sembène, Raj Kapoor and Amar Akbar Anthony with the same passion. We also continued India’s historic solidarity with Palestine while filming there in 2009. And working with historic trade routes and sea farers across the non-national western Indian ocean is also a privilege. This is as an artist working from the Global South. India is like this big bully, and now ultra-right-wing nationalist and hostile to most neighbours. The art scenes from Colombo, Kathmandu and Dhaka are more welcoming and hospitable. You can exhibit Pakistani artists there—that is not possible in India at the moment.

AS: Globally, there is a lot more diversity among practising artists, which is great and very necessary. There are a lot of new subjects, positions and lived histories. We need some level of collaborative thinking, some joining of alliances and strategic solidarity because otherwise our ideologies get easily picked up in different ways by different powers. There is a lot of work to be done.

Installation view, Bombay Tilts Down, 2022. CAMP, To See is to Change, Design Hub Gallery, Melbourne, 2024.

In case you missed the first part of the conversation, read it here.

To learn more about CAMP, read Ankan Kazi’s essays on Bombay Tilts Down (2022) and The Neighbour Before the House (2009–11), as well as Gulmehar Dhillon’s reflections on A Photogenetic Line (2019).

All images courtesy of CAMP. Images by Christian Capurro.