Against Abstraction: In Conversation with Maen Hammad and Dina Salem

In this edited conversation with Kamayani Sharma, Palestinian photographers Maen Hammad and Dina Salem speak about Against Abstraction, an activation they initiated with Sari Tarazi and Ahmad Alaqra at Arles from 1 July to 7 July 2024, supported by DoubleDummy Studio and Tanvi Mishra. Aggregating and algorithmically analysing audiovisual media from Gaza circulating on local Telegram groups, the project collates a timeline of the ongoing genocide. Hammad and Salem discuss the challenge of representation under the hegemony of Western corporate media and elaborate on their process of reconstructing a chronology of resistance. Speaking about their newsletter Unbranding Liberation, released alongside the display of the timeline, Hammad and Salem discuss how images of Palestinian trauma are made abstract by the twin forces of capitalism and colonialism. By sourcing and displaying material from Gazans circulating on encrypted platforms, Against Abstraction critiques the co-option and effacement of their suffering in a dominant visual culture determined by the codes of occupation.

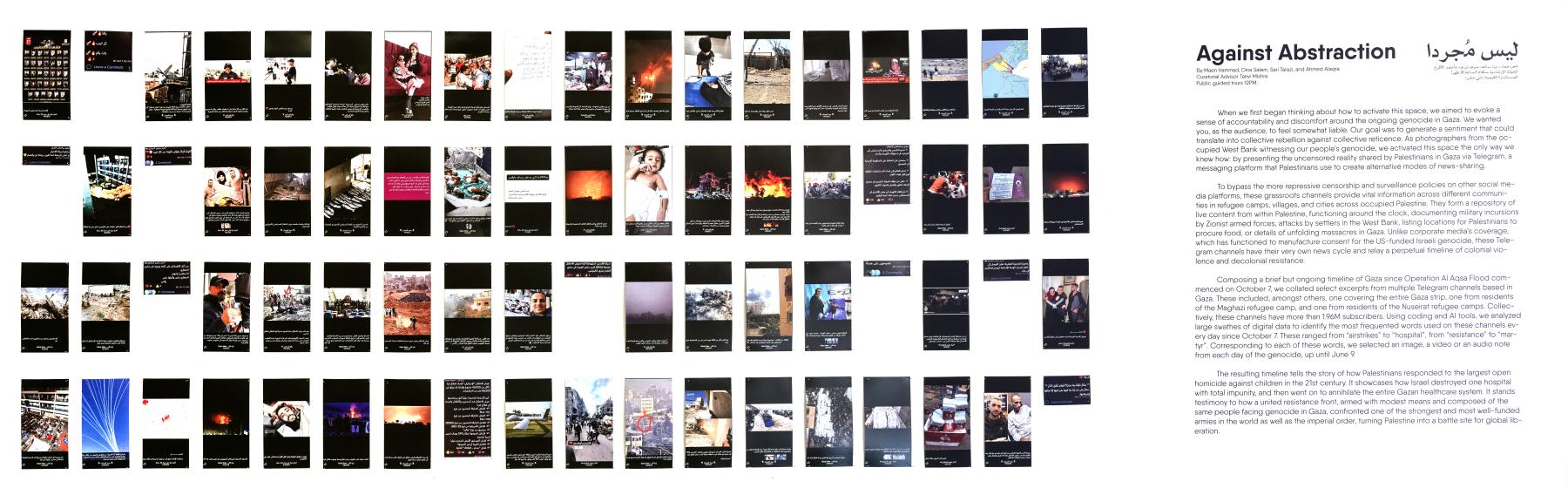

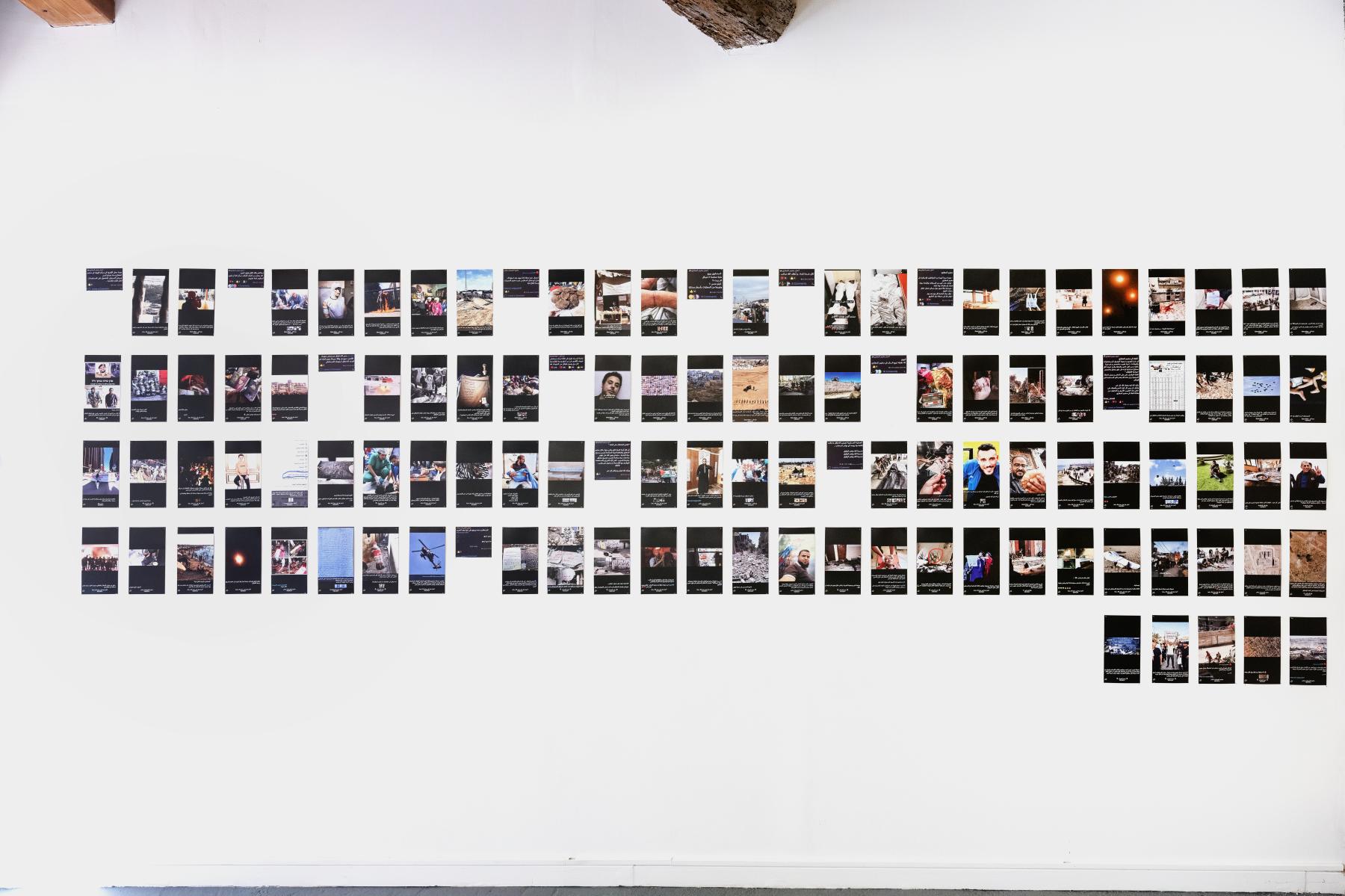

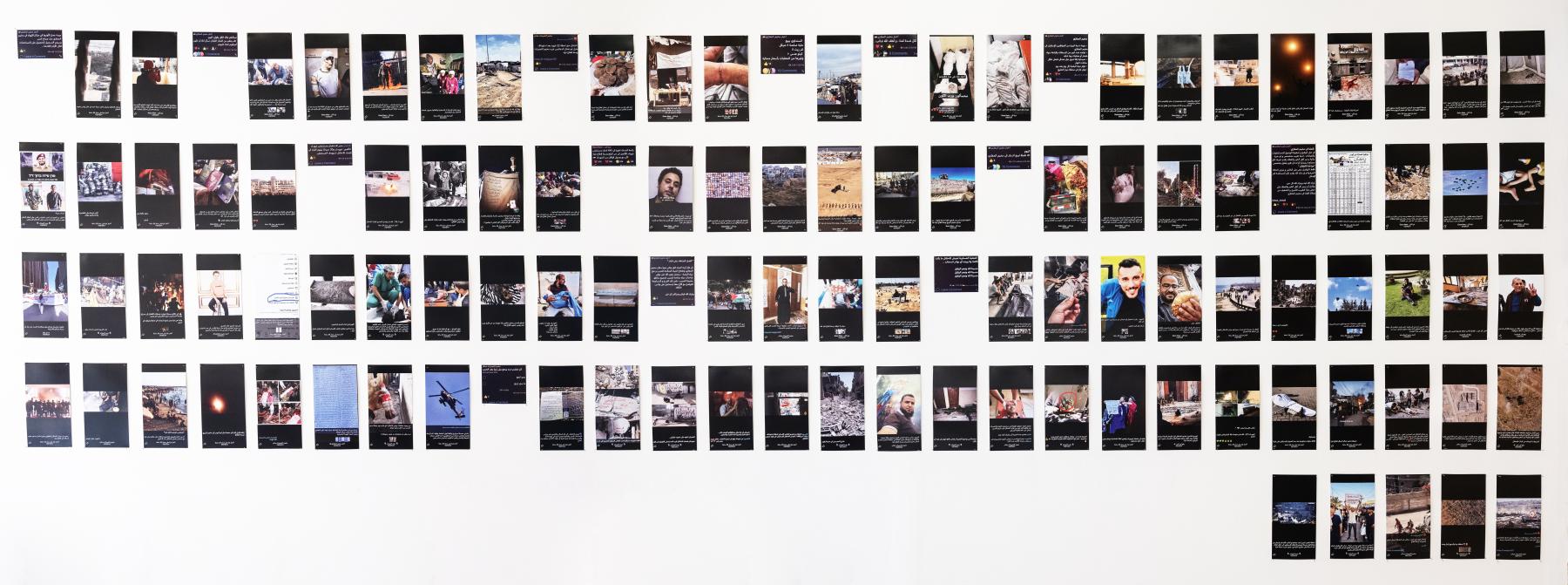

Installation image from Against Abstraction.

Kamayani Sharma (KS): Can you describe the logistics of aggregating and analysing material from Telegram channels? What were the challenges and rewards of this approach?

Maen Hammad (MH): We were overwhelmed initially. Telegram is obviously the source material for this activation, but there are thousands of messages a day from hundreds of different groups. It was like…

Dina Salem (DS): A database.

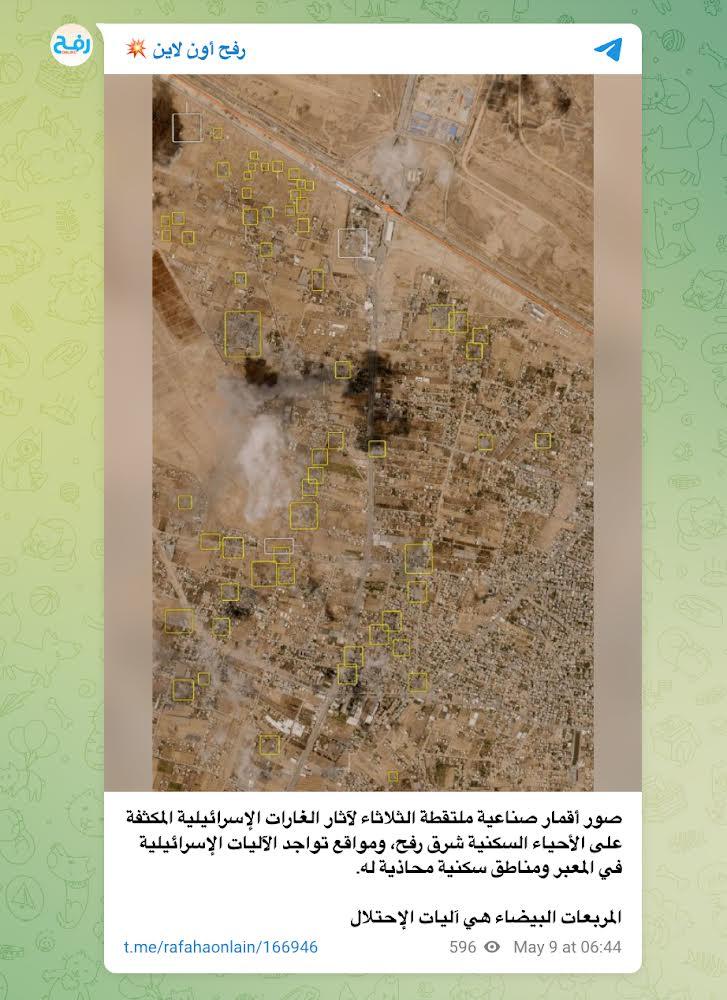

MH: One of the co-activators was able to use AI tools to aggregate the most used words per day across seven different channels. He used Python coding to create huge Excel sheets that had a thousand tabs every day. Then we would take the most used words to go back to the day in question and source one video, photo or audio note that contained those words. For example, on a certain day, it would be a very specific neighbourhood mentioned eighteen times in one group chat. And ostensibly, that meant nothing, right? But if you go back into the Telegram group, you see this story, “The Israelis are saying they're going to strike this neighborhood.” Then a few other videos show the evidence of that strike. A few other videos also show the martyrs from that strike.

And you get this very real story, evidence from Palestinians in Gaza who are everyday people documenting their genocide. It eventually became this research deck where we could then source the screenshots, print them on this very ironic fine art paper and use the stories from people in Gaza to provide this self-narration of a timeline.

A screenshot from the "رفح أون لاين" Telegram channel on 9 May 2024. Translation: "Satellite images taken on Tuesday of the intense Israeli airstrikes on residential neighborhoods in east Rafah, and the locations of Israeli vehicles at the crossing and surrounding residential areas. The white squares are Israeli vehicles."

KS: I am reminded of Edward Said’s essay “Palestinians Under Siege”, in which he talks about the maplessness of Palestinians. Timelines are a kind of chronological map, so his term could also refer to temporal suspension. What does the visual format of the timeline or, rather, the “counter-timeline” enable politically and aesthetically?

DS: Things are very difficult to historicise in Palestine because the violence is ongoing, it is a core aspect of our daily lives. And so I think about this dichotomy of history and memory, in that Gaza is the only place on earth where time is different, where everything has changed, where the world has just completely turned on itself.

Even when I think about the first hospital that Israel bombed, it feels like it happened so long ago, but actually it really was not that long ago. I think that is what this timeline achieves and shows. Just how easy it is for colonial violence to elevate itself right before our eyes. And we are not even aware of it, because people are just scrolling through the events in Gaza.

KS: In your newsletter Unbranding Liberation, you connect the visual strategy of abstraction to the ideologies and practices of colonialism and capitalism, as you pointed out. Can you elaborate on how you resist these processes of political economy through a critique of the abstract image?

DS: Under capitalism, the idea of liberation is abstract in and of itself. Palestine has become something abstract. We are referring to this relationship between capitalism and colonialism for its tendency to not only abstract such ideas but also appropriate them. Even anti-Zionism is liable to be appropriated under capitalism.

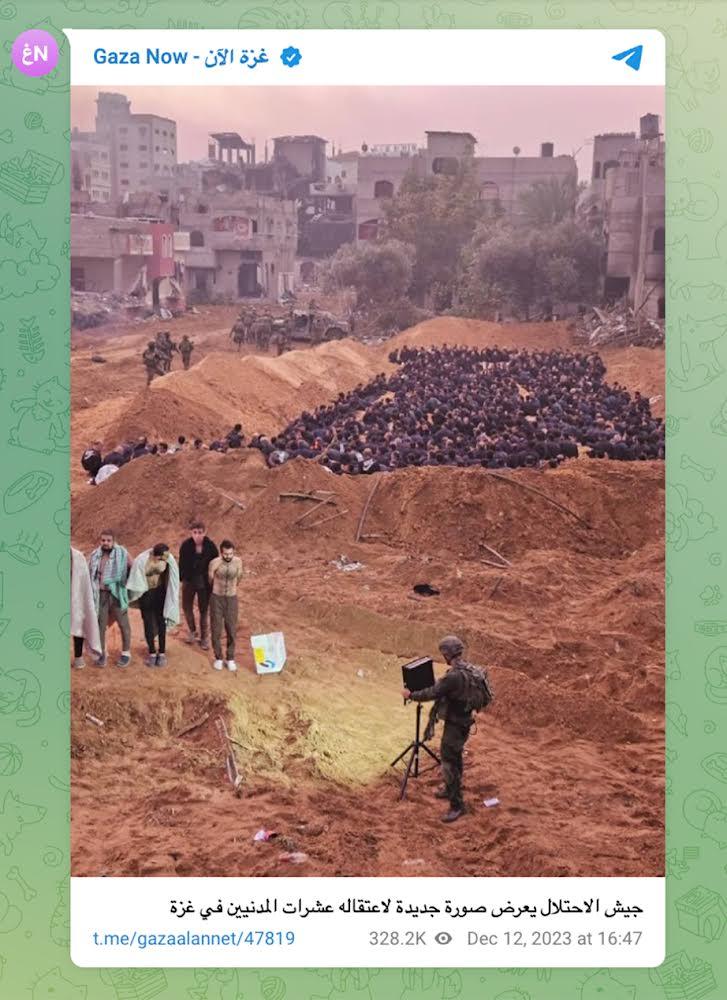

This is what we refer to in the newsprint as trends of consumption. These ideas have already been abstracted and stripped of their meaning for colonised people to become commodified, digestible and consumable. People in Gaza have been reduced to bodies on screens and videos such that you can see a video of a child who has been orphaned, and you are just able to move on from that; you do not have to return to it. So there is this disconnect between us and people who are actually undergoing genocide that makes them invisible in our own minds, not just through censorship and surveillance. We ourselves also cease to see them.

Installation image from Against Abstraction.

MH: You can have slogans on or about Palestine that end up breaking news or creating this rumble, but those are not the words used by Palestinians living the reality of genocide.

And I guess this project was an exploration of what their words, videos and source material are to provide this counter—that is, I cannot say 100 percent unabstracted because we are looking at it through a screen using different tools, 50 miles away—but it is a bit closer to what is being shared from Gaza.

KS: How do you view this problem of visually representing violence in an age of social media? On the one hand, Palestinians are more in control of narrating the truth of occupation than perhaps ever before—TikTok intifada is a term that keeps circulating in the Western media. At the same time, they experience apartheid and occupation in the digital realm.

DS: I do not know if it is about telling the truth anymore, because narrating the truth is a burden on the oppressed and the colonised. We have always known what Zionism is—that it rests upon the extermination of Palestinians. This has been our life all along. It is a tired conversation. If those images—after more than 300 days—are not enough to end the genocide, I think that has to make us question the very idea of representation and of relaying experiences to others through social media.

MH: It is this double-edged sword where mainstream social media platforms are showing more of what is happening, but it is this incomplete picture. To the point of this TikTok intifada, one good thing is that there is a whole new young generation that is seeing the very material costs of capitalism and colonial violence, as well as the resistance.

I just do not believe that seeing through a screen will liberate Palestine. I guess one concern with this short-form digital consumptive model is that it can be very superficial and serotonin-based. What I am more interested in is how these digital tools can provide openings for people to do more important things offline.

DS: Political education does not come from a TikTok video.

Solidarity itself needs to be reimagined. It is not enough to know. It is not enough to bear witness. Liberation requires sacrifice. These are the ones that really suffer the consequences of surveillance and censorship and all the mechanisms that exist to demobilise and suppress.

A screenshot from the "Gaza Now - غزة الآن" Telegram channel on 12 December 2023. Translation: "The occupation army shows a new picture of its arrest of dozens of civilians in Gaza."

KS: I was thinking about your project also in conversation with the more recent turn to forensic investigations like those conducted by Forensic Architecture and Bellingcat, etc. They too are abstractions of visuals from occupied Palestine.

MH: Forensic Architecture and forensic investigations provide important documentation and evidence. But rarely are they talked about or used by Palestinians. It tacks onto this long list of reports and frameworks that are regurgitating what Palestinians have been saying since 1948—that this settler colonial project wants to kill us, remove us, erase us and take our land and natural resources to appease one people over another.

We use open source tools, but in and of itself, it was proof that there is a completely different reality in Gaza, that Palestinians, the victims of the genocide, are filming, recording and sharing. For a project against abstraction, that is a very different starting point from a research investigation into an individual massacre.

DS: There is also this underlying need to lend credibility. An investigation indicates that there is a possibility that the hospital was not bombed by Israel. We do not need the New York Times or Forensic Architecture to tell us who bombed the hospital.

We know those things. What we need is for it to stop and for accountability to be in place.

Installation image of Against Abstraction.

To learn more about questions of representation with reference to the genocide in Palestine, read Najrin Islam’s essay on Palestinian filmmakers reclaiming their narrative and Radhika Saraf’s three-part essay unpacking W.E.B. Du Bois’ notion of the colour line.

Images courtesy of DoubleDummy Studio, unless mentioned otherwise.