Kaagaz Ke Phool at Metro: Nostalgia Tethered

As we settle into our seats to watch the film, a young girl—around ten years old—skips along the aisle to the front. Shortly after, an older man follows, gripping a wooden walking stick, dressed in a crisp white shirt and cream trousers. A moment later, a woman follows slowly, with fresh flowers decking her hair along with a pearl necklace, shimmering earrings and bangles. The scent of fresh flowers and the formal attire provide a pleasant surprise, an unexpected layer—suddenly elevating the afternoon to the air of an opening night. Guru Dutt’s cult classic Kaagaz Ke Phool (Paper Flowers, 1959) is the fare for the Sunday matinee at the iconic Metro, now suffixed with an INOX testifying its allegiance to the world of multiplexes. While purchasing tickets, I had prepared for a possible trickle of ‘nostalgic’ emotions but did not foresee this dramatic prologue enacted by these three characters. The appearance of an imagined ‘past experience’ needs scrutiny because it overwhelms the senses. It invites us to examine some possible deeper sense of nostalgia that is not wafer-thin and caught in the curvature of Art Deco, something that also invokes a possible ethical longing.

The protagonist (Guru Dutt) returns once more to the summation of his life—his past, the film studio and his craft.

The film opens with an older man, Suresh (Guru Dutt), visiting a film studio filled with equipment and constructed sets. His deep-set eyes, full of despair, scan what appears to be an inertia within the emptiness. The story beckons us through a flashback into his life as a director at the peak of his career, devoted to his craft. It evokes the familiar trope of the maestro—surrounded by subordinates committed to his vision. Also, a sense of personal chaos is represented through his broken family—including an estranged wife living with her wealthy parents and a daughter in boarding school.

Shanti (Waheeda Rehman) stumbles into the live set.

Meanwhile, Suresh has a chance meeting with a young woman, Shanti (Waheeda Rehman), as they coincidentally seek refuge under a tree during a storm. Shanti, who has no family, travels to Bombay to return a coat Suresh had given her. While waiting for him at the studio, she stumbles into a live set and is caught on camera.

The attire, the dimness of film-screening room and the crew standing in deference to the "creative" vision of the protagonist together attempt to portray an element of "wonder".

Seeing the rushes from the day, Suresh decides to make her the star of his next film. As they get to know each other, they are increasingly besotted with one another. This reaches its culmination when she takes care of him after he is hurt in a car accident. However, a short while later, she is condemned to a life of self-imposed isolation triggered by the protagonist’s anxious daughter’s inability to accept the new romance.

The trope of the fallen hero serves as an internal guide towards making the audience long for the past (within the film).

This sets in motion a fall from grace for the protagonist. As the romance sinks into its own moral uncertainty, the maestro-artist collapses into alcohol-infused agony. An earnest, sincere life as an artist and individual only allows meagre support for the fallen protagonist as this downward spiral is unleashed. His former chauffeur gives him refuge. His lover forgoes her exile in films, making a deal with the producer to renew the protagonist’s career. He refuses to relent, unwilling to compromise with anybody while sinking into his own moral abyss. His final moment takes place at the director’s seat on his old set. We return to the silence of the opening scene that ends as the final flourish. Amidst the commotion and a storm, the emptiness is displaced. A strange longing and a possible nostalgia—swelling through the film—culminates with the appearance of the text ‘THE END’.

With a disdain for fanfare and an obsession surrounding the craft, Suresh is disappointed with Shanti attending a party when a shoot is due soon. Moral uprightness merges with excellence, which becomes the bedrock of virtue in the internal value structure that the film constructs.

The obvious motifs of an ethical self-abnegation, compassion and love are contrasted with selfishness, greed and indifference. Meanwhile, misogyny, patriarchy and a disdain for the unfortunate are present in expected doses. The protagonist’s brother-in-law, Rakesh a.k.a ‘Rocky’ (Johnny Walker), valorises an ‘unhindered’ life of bachelorhood as some sort of peculiar freedom from attachment. Suresh has this odd sense of superiority as he seeks to control Shanti’s appearance, questioning her commitment to the craft at times. On the other hand, he stubbornly refuses her help or assistance to renew his career. Then where (or even why) does one seek or find nostalgia in such a world of emotions and characters that both attract and repel in equal measure? Or is there a world of things and rendered histories that make us continuously produce our own version of nostalgia, not necessarily rooted in ethical content?

Scraping the surface of this ‘nostalgia’ matters, especially since this surface of “Art Deco” Mumbai/Bombay tends to limit itself to appearance and its attached fanfare, lending it a golden-era visage. The sets, the songs, the cars, the clothes and the scent of recently ‘decolonised’ (or maybe recolonised) people—with their summer dresses and well-tailored dinner jackets—provide a savoury charm to many. Do these then act as metaphors for longing for unwrinkled moments? Are these simply parodying a longing for a version of simplicity that ‘elite’ memory consumes and maybe desires? Is this then the source of nostalgia—of a lost past? Or is this merely a projection of a sub-par present that triggers yearning?

One would assume that it is difficult to separate the two. A recent spurt of screenings of classic films from the ‘golden black-and-white era’ appear to mark a burgeoning infrastructure of nostalgia. S.A. Howard refers to the “poverty of the present requirement”, where nostalgia emerges from a feeling that the past was better than the present. What matters is whether memory is constructed as much as it is remembered by an increasingly shared public imagination actuated by social media. Does the separation of remembering and constructing the past signify intention with reference to how nostalgia is deployed? After all, the professional historian—who assembles (constructs) history—may leave the remembering and nostalgia to the ordinary pedestrian.

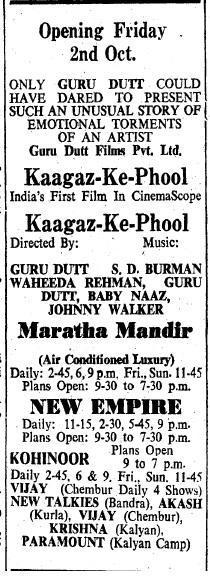

Advertisement for the premiere of Kaagaz Ke Phool. (Image credit: Times of India archive.)

Released on 2 October 1959, Kaagaz Ke Phool premiered a short walk away from the now PVR INOX Metro at the New Empire (among other cinema theatres in the city). The building stands abandoned, hidden in a lane opposite the iconic Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus (erstwhile Victoria Terminus). While Howard calls attention to the “irretrievability of the past”, this experience seems to suggest ‘retrievability’ produced through the present. A present that is an assortment of shards, blunted or sharpened by our shared lives. The news ‘ticker’ tells of persisting humiliation and violence for marginalised peoples, endless wars, millions dead or dying, natural disasters and the shrinking space for justice and freedom. Social location continues to define one’s grade and status. In this scenario, nostalgia can serve as a longing for the past. But when do we deploy it and when do we choose to ignore it?

If films can offer us an opening to pierce the present with the past, can it transform the everyday into a mode of seeing broader global dynamics? For instance, the 1960 Filmfare Awards were held at the Regal cinema. At this event, Kaagaz Ke Phool won awards for the best art direction and best cinematography. Gamal Abdel Nasser, then Egyptian President and leader of the 1952 Egyptian Revolution—which contributed to the development of Third World solidarity during the Cold War—was the distinguished guest who presided over the award ceremony.

.jpg)

Gamel Abdel Nasser at the 1960 Filmfare award ceremony. (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.)

Does the politics of “non-alignment” and collaboration within the global south urge nostalgia in the present context? This fact possibly troubles the present, as much as it distances the past. The memory of a friendly head of state attending a commercial film award function evokes nostalgia for many reasons—anti-imperialist foreign policy being one of them. But, if nostalgia attempts to valorise the past, we are reminded that governments (of undesirable hues) can imitate these gestures to display their commitment to films that antagonise any possibility for an anti-imperialist collaboration. Nostalgia, it would appear then, is irrevocably tethered to the moment that produces it.

To learn more about the screening of films from the past in contemporary commercial spaces, read Sucheta Chakraborty’s essay on the restoration of Shyam Benegal’s Manthan (1976).

All images are stills from Kaagaz Ke Phool (Paper Flowers, 1959) unless mentioned otherwise.