Restoring Manthan: Cinephilia in the Age of Multiplexes

“A PVR is almost like a McDonald’s. It's like a franchise which is in every mohalla, every corner, every neighbourhood. At a time when people couldn’t go out of their houses and were watching everything online, I wanted to make it possible for cinema to reach the closest place they could be,” filmmaker, producer and archivist Shivendra Singh Dungarpur relays over a phone call. The founder-director of the Film Heritage Foundation recently helmed a resoundingly successful restoration project of Shyam Benegal’s Manthan (The Churning, 1976). The restored film, which is about Gujarat’s dairy cooperative movement, travelled to foreign shores and then was recently rereleased back to the Indian public—a full circle given that the film was famously financed by half a million dairy farmers who had each contributed Rs 2 towards its production.

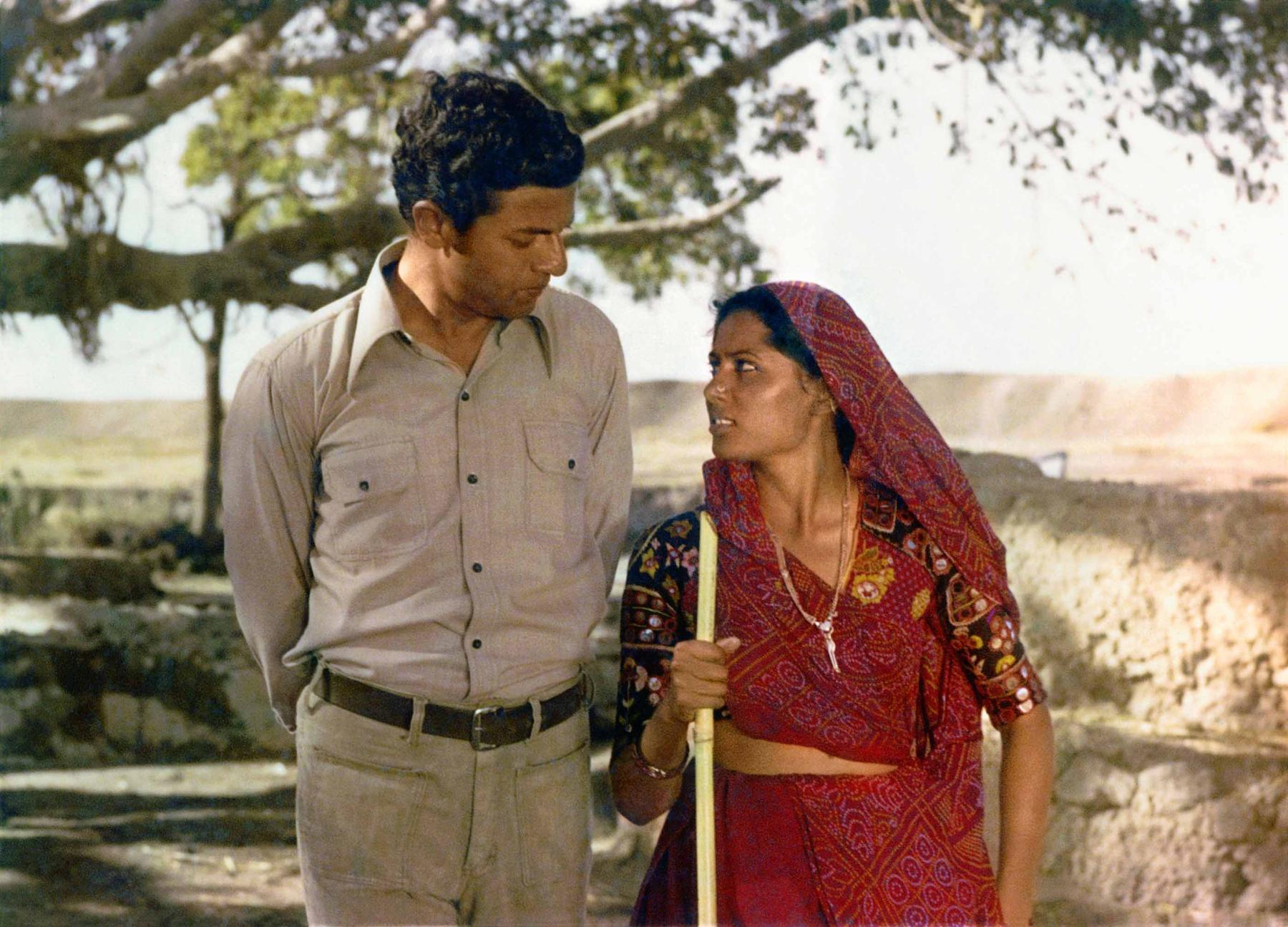

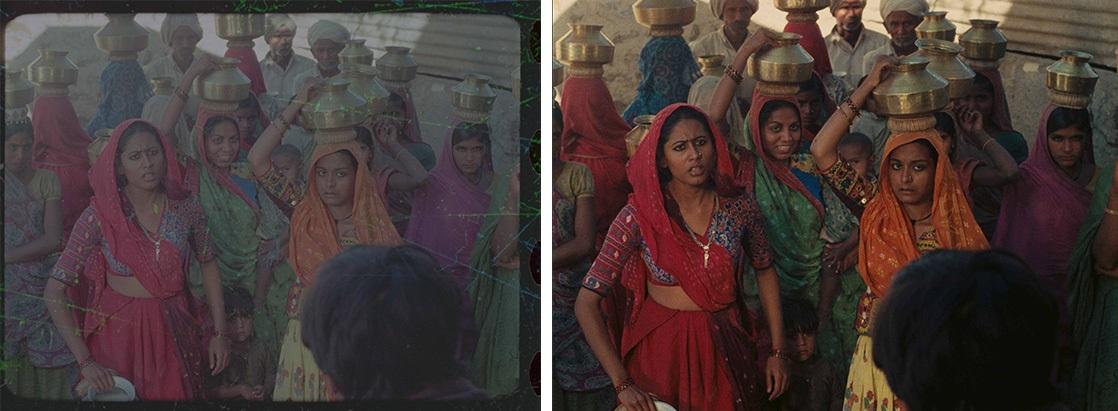

Still from the older digitised print version of the film (left) and the restored film still (right) from Manthan (1976) featuring Smita Patil.

The idea of screening old classics outside of the hallowed spaces of cultural organisations and festival retrospectives by bringing them to your friendly neighbourhood multiplex was one Dungarpur first championed back in 2022. On the occasion of Amitabh Bachchan’s 80th birthday, the Film Heritage Foundation organised “Bachchan: Back to the Beginning”, where eleven of the superstar’s films from the 1970s and ’80s were screened at PVRs in seventeen cities across the country over four days. “It stemmed from the fact that I'm still a big Bachchan fan,” Dungarpur shared. PVR INOX’s Managing Director Ajay Bijli’s initial offer was of a single theatre, but at a time when people were still reticent about going to watch movies in person, Dungarpur insisted that nostalgia might help fill seats again. Bachchan himself, Dungarpur recalls, suggested that some of his more recent films be screened, but the film restorer held firm to his original idea.

.jpg)

Photographic still from the making of Manthan (1976), featuring director Shyam Benegal, DOP Govind Nihalani and the film crew.

The almost unexpected enthusiasm the retro-festival received, motivated the Foundation to host others like it, commemorating the centenaries of actors Dilip Kumar and Dev Anand. There were also standalone events, such as Kamal Amrohi’s 1949 classic Mahal, being screened in 35mm at Mumbai’s Regal Cinema. “A thousand people turned up on a rainy day in Bombay to watch the film. There were people from Ashok Kumar’s village in the audience,” Dungarpur recalls. While a younger generation discovered the charms of watching these classics for the first time in the way their makers intended, for older audience members, Dungarpur believed they rekindled memories of relationships that had once been forged at the movie theatre. At the same time, there was also something of their collective moment that seeped into this eager reception. Dungarpur recalls, “It was not just cinema they were celebrating. They were celebrating life itself, survival and [the triumph over] Covid. There was the happiness of sharing an experience after having been confined into spaces and situations that, in many cases, had been very tragic.”

An archivist compares film stills as part of the restoration process at the Film Heritage Foundation.

Manthan’s release set a new record not just because of its wide distribution—the film screened in fifty-one cities, in over a hundred cinemas—but also because it was the Foundation’s first full-fledged restoration that was shown to the public. “In the case of the Bachchan, Dev Anand or Dilip Kumar festivals, the films were restored by the respective private parties like Shemaroo and Ultra,” says Dungarpur. “We were only showcasing the films to create awareness of our film heritage. But Manthan was our restoration. People could see the difference. They could see the grain, the beauty of the film image. It set the standard for restoration in India.” The biggest takeaway, he says, has been the discourse around restoration in the mainstream, which he considers a first for India. “When people started talking about restoration, it meant they could see what the difference was in the other restoration compared to this. Our aim was to not only make people aware of preservation and heritage, but also of what restoration exactly entails.”

Shyam Benegal (left) and Shivendra Singh Dungarpur (right), viewing the restored film reel of Manthan.

Cinepolis and PVR screens showed Manthan in cities like Muzaffarpur, Bhatinda and Patna. In Kolkata, shows were sold out, with requests pouring in for more screenings. “It took over everything in cinemas on those two days. It did better than the recent releases,” Dungarpur tells us. He pointed to how multiplexes enabled a situation where old films, albeit for just two days, competed with the sales of tickets for contemporary films, even doing better in the absence of worthy new contenders. Moreover, in a video released by the Foundation to announce the screenings, Shyam Benegal recalls how “[in 1976], the film opened [in cinemas] all over Gujarat and farmers came to Ahmedabad and Vadodara to see the film. You had this strange sight of people coming [from outside] in bullock carts and on foot [and gathering in large numbers]”. It is interesting to note that nearly fifty years later, it is the multiplex that has become the site for a renewed interest in film heritage and reversed that journey, attempting to bring the film to more viewers across cities.

Girish Karnad and Smita Patil, in a still from Manthan, restored by the Film Heritage Foundation.

When the multiplex format appeared in India in the late 1990s in the era of economic liberalisation, implicit in its institution was the logic of social exclusion and filmic diversity, where different kinds of films would be made and shown to an increasingly middle and upper middle class audience. Gita Viswanath writes about the altered economics of filmmaking encouraged by the multiplex theatre in The Multiplex: Crowd, Audience and the Genre Film (2007). Viswanath mentions that the move away from the production of “complete entertainment packages” of the earlier decades paved the way in the early 2000s for several low-budget, issue-based films focused on specific themes and styles that also refrained from using big stars.

Original film still (left) and the Film Heritage Foundation’s restored still (right) from Manthan.

Films like Manthan may not have been made in the multiplex era; but given their specificities seem to be filling up a space for films on critical issues created by the format of the multiplex, and indeed thriving in it. Other restorations by the Foundation, like Aribam Syam Sharma’s Ishanou (The Chosen One, 1990) and Nirad Mohapatra's Maya Miriga (The Mirage, 1984) are slated for release in the Northeast and Odisha respectively. There is a point to be made about film culture arguably retaining its nostalgia, through large numbers of viewers seeking “low-quality” restorations uploaded or re-uploaded on freemium platforms such as YouTube by Shemaroo, Usha, etc. But the fact that the mechanics of the multiplex—which, free from the pressures of having to fill 1000-seater single screens daily, could allow for more specialised films to exist—has made it a natural fit for these restorations is worth considering. Dungarpur's efforts have clearly zeroed in on a sweet spot where films like Manthan have found a new home and audiences used to watching different kinds of films. Like the restorations then, the format of the multiplex itself seems to have been responsible for granting these films a second lease on life.

.jpg)

Smita Patil in a promotional film still from Manthan (1976).

To learn more about different archival engagements with film, read Ketaki Varma’s two-part essay on Project Cinema City (2008–13), Najrin Islam’s conversations with Anuj Malhotra on the Garga Archives and with Mariam Ghani on her work with Afghan Film Archives, as well as an editorially curated album from the publication Filmi Jagat: A Scrapbook (Shared Universe of Early Hindi Cinema).

All images are courtesy of Shyam Benegal, Shivendra Singh Dungarpur and the Film Heritage Foundation.