Humanity After Nuremberg: The Colour Line

Since 7 October 2003, Israel has dropped 75,000 tonnes of explosives on Gaza, displacing over 1.7 million people, 80 percent of the population. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

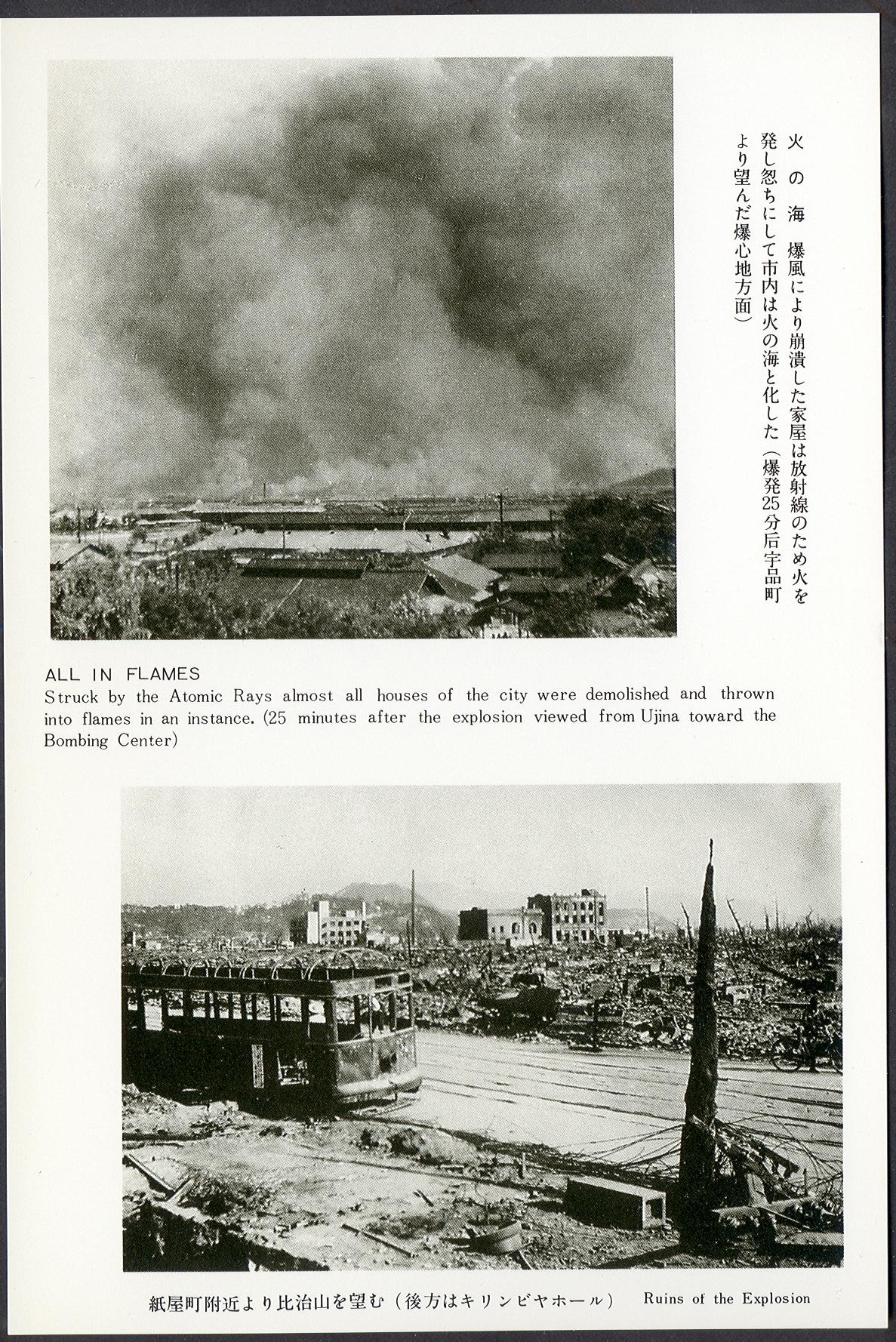

Since 7 October 2023, Israel has dropped at least 75,000 tonnes of explosives on Gaza. This is nearly double the combined explosive effects of the world’s first nuclear bombs, dropped by the U.S. on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, of 15,000 and 25,000 tonnes respectively.

On 6 August 1945, the US detonated the first nuclear atomic bomb on Hiroshima, killing an estimated 1,40,000 people. (Image courtesy of Flickr.)

Yet, while Japan was tried for its involvement in World War II, particularly the killing of civilians across its colonial territories, America was never persecuted for the killing of over 200,000 Japanese people, overwhelmingly civilians, in Hiroshima and Nagasaki alone. In this three-part series, I examine the Soviet-produced documentary Nuremberg Trials (1947) by Yelizaveta Svilova, the docu-drama mini-series Tokyo Trial (2017) by Pieter Verhoeff and Rob W. King and footage from South Africa’s genocide case against Israel (2023), as well as interviews of the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC). I want to think through W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept of “the colour line” as instructive in the contemporary qualification of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

First Photograph of the International Military Tribunal of the Far East in Tokyo, which the Allies began on 3 May 1946. (Image courtesy of University of Virginia Law Library.)

From 1946–48, the International Military Tribunal of the Far East—also known as the Tokyo Trial—organised and held under the aegis of the U.S. as one of the war’s victors, tried twenty-eight Japanese officials for crimes against peace (also known as wars of aggression), war crimes and crimes against humanity. Following from the Nuremberg Trials in 1945-46, which changed the purview of international criminal law from establishing the code of conduct in war to judging the legality of war itself, the Tokyo Trial demonstrated the commitment to a new world order wherein history would “never again” be repeated.

Documentary (Russian Version).jpg)

At the Nuremberg Trials, it was said from the ditch of death, the dead will rise to witness justice. (Still from Nuremberg Trial, 1947.)

If in Nuremberg, where the Nazis might have been individually insignificant in the fascist machine but “represented living symbols of racial hatred, of terrorism and violence, and of the arrogance and cruelty of power,” so too in Tokyo. If in Nuremberg it was said, “into the courtroom will come the martyrs… the dead will rise, they will rise from the graves… and the children, they too will come… now the victims will judge the butchers,” so too in Tokyo. However, unlike the unanimous verdict at the Nuremberg Trials, the Tokyo Trial saw three dissenting verdicts. The fiercest disagreement came from the Indian appointee to the tribunal, Justice Radhabinod Pal, on the grounds that Japan’s actions cannot be divorced from the context of the colonisation of Asian peoples, bringing to light also the atrocities committed by the U.S. in Japan. Thus, if Nuremberg formed a constitutive exception for the persecution of Europe in war crimes, the Tokyo Trial engenders what can only appear to be a “colour line.”

In an article entitled “The Color Line” (1881), the American abolitionist Frederick Douglass explained how slavery may have ended the “money motive for assailing the Negro” but not the “love of power and dominion.” If Douglass considers “the color line” as a structure of segregation within America, W.E.B. Du Bois expands the concept to articulate the problem of racism globally. Thus, in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), Du Bois writes: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.”

Elaborating on this problem in an analysis of “The African Roots of War” (1915), Du Bois speaks of World War I as a competition of the “spoils of trade-empire” between European nations who “look for expansion, not in Europe but in Asia, and particularly in Africa. ‘We want no inch of French territory,’ said Germany to England, but Germany was ‘unable to give’ similar assurances as to France in Asia,” he writes sardonically. Moreover, through the imperial capital’s “public threats of competition by colored labour,” the European world over is now taken by the assumption that “if white men do not throttle colored men, then China, India and Africa will do to Europe what Europe has done and seeks to do to them.”

Documentary (Russian Version).png)

The Soviet prosecutor recalled that 9 million people from occupied territories were packed in railways to be carried off to slavery. (Still from Nuremberg Trial, 1947.)

In a scene from the Nuremberg Trial, which primarily utilises stock footage, the voiceover states “Hitler said, ‘Germany needs slaves, many slaves’, and the slaves—men, women and children—flowed in a never-ending stream to the slave markets of Germany… to unbearable toil and early death. This was the appalling fate the Germans had planned for all mankind.”

Slavery had been the basis of Western capitalism from the sixteenth century onwards; except until then, Europe was built on the trans-Atlantic slavery of coloured peoples. Yet, this moral outrage at the fate of Europe was welcomed the world over; in fact, a majority of the Allied forces came from its colonised territories, with 2.5 million Indians and over a million Africans contributing to the war effort. While WWII led to the persecution of Nazi officials for war crimes, in 2024, despite South Africa’s case against Israel at the ICJ and the recent ruling of the ICJ declaring Israel’s presence in Palestine as unlawful, Israel continues unabated, supported by its allies in the West, particularly America and Germany. This brings into question whether the phrase “Never Again” for crimes against humanity, Nuremberg’s knell, is reserved only for Europe? Does it not extend to Asia, Africa and the Middle East?

Formerly enslaved people at Boone Hall Plantation in South Carolina are amongst the 12.5 million Africans who were transported to the Americas by European and American slave traders between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. (Image courtesy of Flickr.)

Recalling Aime Cesaire’s Discourse on Colonialism (1950), wherein he says the following with reference to the Christian bourgeoisie of the twentieth century, can prove useful:

“What he cannot forgive Hitler for is not the crime in itself, the crime against man, it is not the humiliation of man as such, it is the crime against the white man, the humiliation of the white man, and the fact that he applied to European colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the ‘coolies’ of India, and the ‘niggers’ of Africa.”

This distinction between “crime against man” and “crime against the white man” would be revealed in the contradiction of the Tokyo Trial, the subject of the second part of this essay.

To read more about postcoloniality in media histories, read Shivani Kasumra’s essay on Navina Sundaram and Ankan Kazi’s report on a conversation between Sinthujan Varatharajah and Suchitra Vijayan.