The Dimensions of Memory: Nostalgia for the Light by Patricio Guzmán

Speaking of the endless expanse of the desert, Guzmán compares it to “a vast open book of memory,” inviting observers of all kinds, particularly astronomers making use of the dry climate to study the cosmos. While the observatories themselves serve a similar purpose of searching for the traces of deeper origins, Guzmán narrates how the translucent skies make for observers in their own right.

Much like the deliberate, discoidal movements of the observatory telescopes that it opens with, Nostalgia for the Light (2010), by Patricio Guzmán, follows the aftermath and impact of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet's regime from 1973–90. Through his resolute narration, Guzmán’s documentary introduces us to the search for a past unravelling in the Atacama Desert in the 1970s. The film draws an important parallel between astronomers and archaeologists researching humanity's past in space and on earth respectively, and the traumatic quest that Chilean women pursue, as they seek the remains of their loved ones who disappeared as political prisoners under Pinochet. The film interviews both the researchers and the women who have sifted the desert for their brothers, sons and husbands for over three decades. It interweaves historical and archival material to substantiate the narrative itself. Over the years, Guzmán’s work has focused significantly on socio-political issues and human rights abuses in Chile; however, Nostalgia for the Light presents a powerful paradox, platforming humanity’s collective question on our earliest origins against the active erasure of our most recent histories.

Lautaro Núñez, a Chilean historian, is emphatic about preserving memory to ensure the dead and the disappeared are never forgotten, asserting his—and a shared national—right to remember the wrongs and wronged of history.

The Atacama Desert in Chile bears a strong resemblance to Mars, reiterated by the fact that nothing lives in its barren expanse. A landscape with a complete lack of humidity coupled with translucent skies and its dry climate, Guzmán explains the desert was a transit route, connecting high plains and the sea. During Pinochet’s reign in the 1970s, it grew into a condemned place. Its salty earth mummified the bodies the dictatorship buried, making it a “vast open book of memory,” as the filmmaker narrates. The film follows how, using its dry environment to perform their research, astronomers built observatories to understand the cosmos. Similarly, harnessing the desert’s ability to preserve traces from the past, archaeologists studied the marks left on mountain facades and on old trade routes. One is urged to ask, how do we traverse the weight of such a site, where weightlessness—of culpability, nationhood and belonging—is not only implied but evident?

The women dig in the desert for fragments of bones that might have remained after Pinochet’s unjust removal of the bodies of the dead in an attempt to prevent anyone from finding them.

Taking us through history, Guzmán shared a glimpse of Chile’s golden age of astronomy that was overturned by the coup d’etat orchestrated by Pinochet in 1973, ending civilian rule. After his rise to power, Pinochet persecuted leftists, socialists and political critics, resulting in the executions, internment and torture of thousands of people, many of whom were imprisoned in the Chacabuco concentration camp. Guzmán is taken through the ruins of the camp by Luis Henriquez, a former prisoner who was part of a small group of people at the site who came together to observe the stars. Astronomy was later banned by the military, who feared that the prisoners would eventually escape. The desert preserves death and memory, and it is unbiased in what it swallows and keeps; as the film shows us, the past is more accessible in some places, particularly in its midst. We are reminded of how, despite yearning to reach the dimensions of galaxies made visible by its observatories, Chile remains in the grasp of its own past, immobilised by a state-sponsored reticence that refuses to acknowledge its actions, avoiding culpability of any kind.

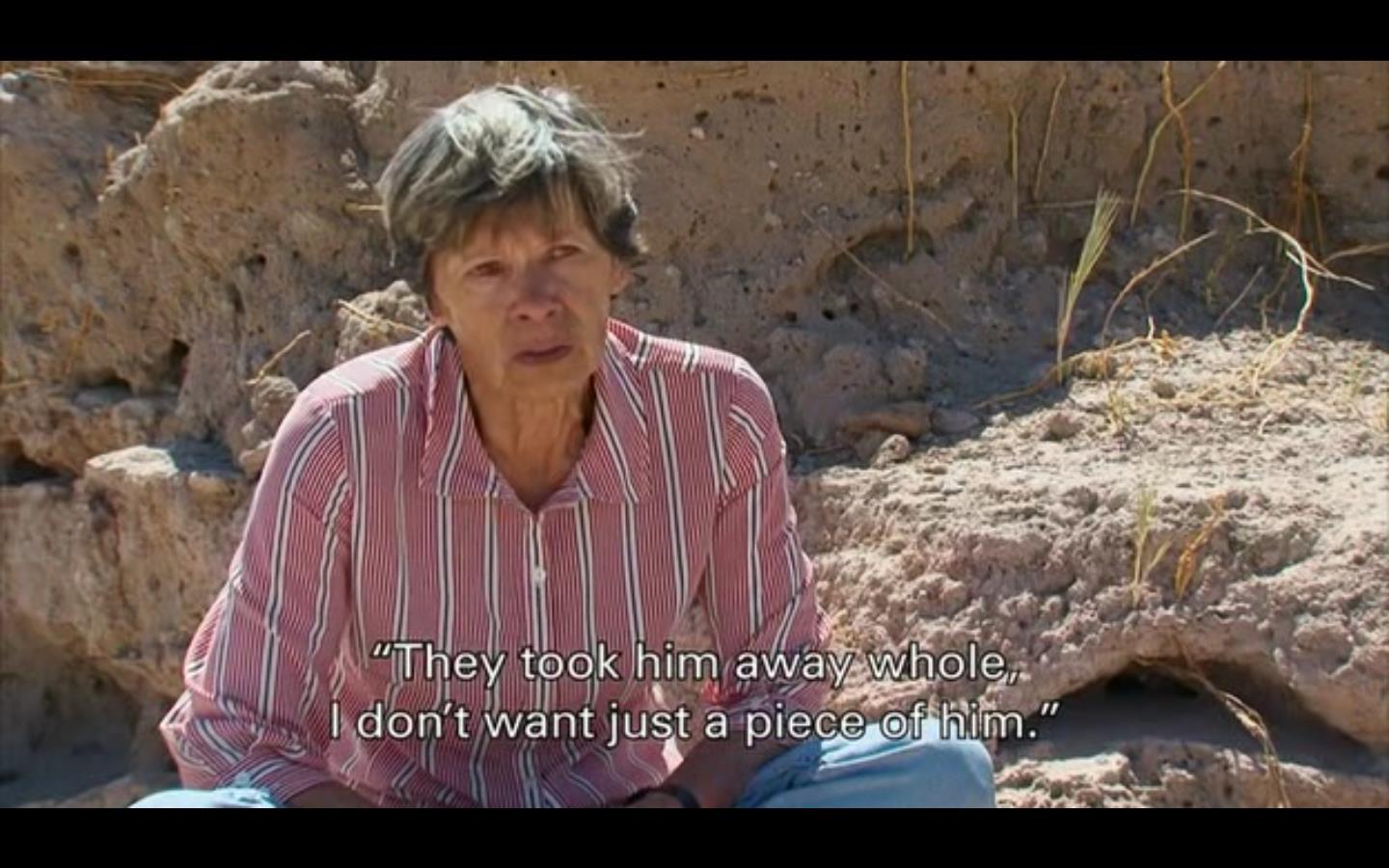

Violeta Berríos recounts her experience of being told searchers had found a piece of her son. Refusing to accept just the fragment, she remains adamant in her hope to find him whole. She wishes the telescopes could also see through the earth because if that were possible, her search for answers would have now been completed.

Nostalgia for the Light focuses on a similarity as well as a difference: we see the astronomers' desire to understand the past and origin of the universe and we see the archaeologists winnowing through the land and its depths. The difference presents itself in the desire for answers that is evident in both these previous examples, but is inclined towards a steep urgency with the women of Chile. The women at the centre of the documentary differ in their scouring for answers, striving for closure, yet receiving only fragments—or sometimes nothing—despite their years of waiting. Guzmán speaks to Vicky Saavedra and Violeta Berríos, determined in their twenty-eight-year-long search to find fragments and shards of bones of their relatives. We are told of how Pinochet assassinated and buried the bodies of political prisoners in the Atacama Desert. To further prevent them from being found, he had them dug up and dispersed—some even thrown into the sea. Guzmán listens to the women speak of how they are viewed as ‘Chile’s leprosy,’ as the lowest of the lows that the state must bear.

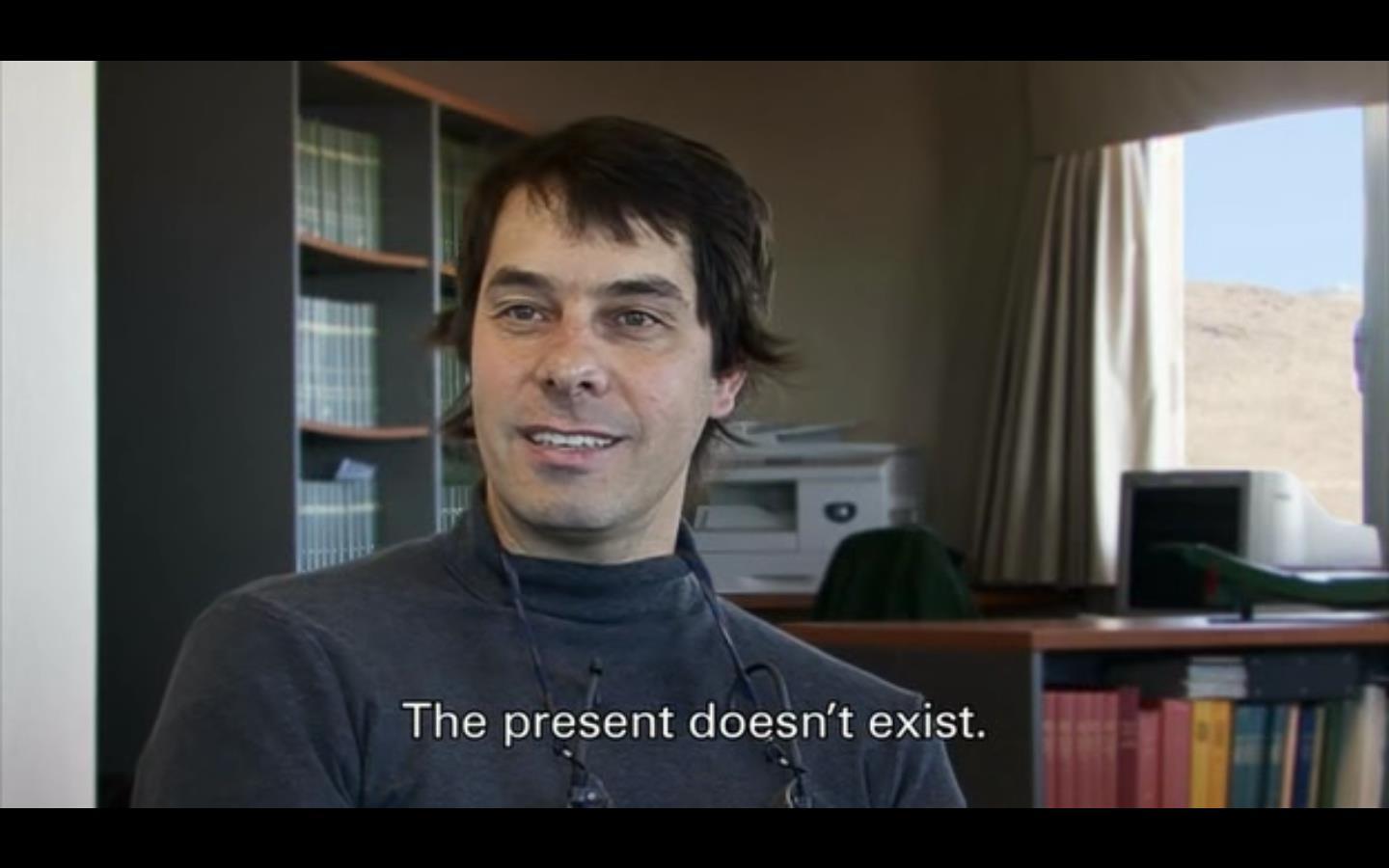

Astronomer Gaspar Galaz appears as a resourceful consultant in the film, piecing together the concepts that drive research in astronomy and the realities that fuel the more traumatic search for answers undertaken by the women of Chile. Guzmán’s decision to include scientists in his film is justified by their immense clarity that does not validate empty positivism but instead urges for more affective, intuitive studies of history and the past.

Guzmán asks a question, also echoed by his interviewees: will the past be remembered? In a poignant declaration, Lautaro Núñez states that everyone must be involved in preserving the memory of such tragedy. In a scene from the film, astronomer and child of detainees as well as disappeared parents, Valentina Rodriguez calmly gestures to the inherent cyclicality of it all—the disappeared and their absences assume new dimensions, where pain and loss is no longer singular and instead tends towards the optimistic; where the strength to endure a search and a waiting is passed down. As the camera pauses before her and her infant son, she speaks of how she feels peaceful knowing the ‘manufacturing defect’ of having witnessed such violence will not be experienced by her children, who will instead inherit her optimism. At the end of the film, the floor of the observatory is lit by sunlight, telescopes are recalibrated and ladders are shifted into place. Guzmán is aware of how the efforts of the women do not converge with those of the astronomers. In a poetic closing scene, we see the converging presences of Saavedra and Berríos in the observatory—reading, looking, searching—into and alongside the cosmos, for a past that refuses to disappear.

Victor Gonzalez, a young astronomer who has grown up as a child of exile, is featured in the film alongside his mother. The latter works to heal and rehabilitate survivors, refugees and family members from Pinochet’s time. While preparing a meal, she tells Victor how it is difficult for the families who lost their loved ones to continually encounter the torturers who walk free on the street as it re-traumatises them.

To learn more about works across South Asia that explore the lives of those who continue to search for their loved ones who have been disappeared, read Sukanya Deb’s essays on Siva Sai Jeevanantham’s In the Same River (2017–21) and Rohit Saha’s 1528 (2017), Anisha Baid’s conversation with Ashfika Rahman on her work Files of the Disappeared (2018–Ongoing) and Annalisa Mansukhani’s reflections on Leena Manimekalai’s film White Van Stories (2014).

All images are stills from Nostalgia for the Light (2010) by Patricio Guzmán. Images courtesy of the filmmaker and Icarus Films.