Staging a Film: Stills from Tagore’s Natir Puja

In 1931, Rabindranath Tagore filmed a version of his stage drama Natir Puja (A Dancer’s Worship) for B.N. Sircar’s New Theatres studio in erstwhile Calcutta. Based on his own narrative poem Pujarini, the play was derived from the Abadan Shatak, a Pali book of Buddhist stories. It recounted the tale of a court dancer Srimati, who sacrificed herself at the altar of Buddha after his religious philosophy was censured by King Ajatasatru. A story of devotion and sacrifice, Tagore wrote the playscript along with his nephew, Dinendranath Tagore. Featuring an all-female cast, it was staged as a drama in the New Theatres studio and then filmed like a record of the production. Natir Puja was released in 1932 by the studio, which was hoping to ride the coattails of Tagore’s increasing fame. New Theatres promised Tagore that half the proceeds of the film’s box office returns would be donated to his experimental school at Santiniketan.

Film Still from the sets of Natir Puja, Rabindranath Tagore’s solo directorial venture. (Photograph by Nitin Bose.)

A review in the newspaper The Bengalee pointed out the rare privilege of being provided access to the amateur dance and stage dramas that Tagore regularly put up with his family members and students in Calcutta and Santiniketan:

“The most striking feature of the film is the interpretative dance of the artiste who played the role of Srimati. To Rabindranath belongs the credit for revival of this ancient Indian art and its inclusion in this film must give an opportunity to many who have not seen it danced by the poet and his pupils during the seasonal festivals he is in the habit of celebrating in Calcutta to see and admire these dances.”

By the 1930s, Indian audiences had already been trained to recognise filmed space as a constellation of techniques and objects separate from the flat, staged space of the drama, irrespective of the subject or genre of the film, as the long history of devotional films attests. The film flopped.

Subsequently, its print was lost in a fire at the New Theatres studio in the 1940s. While efforts have been made lately by scholars and restorers to recover a copy of the film—a crucial endeavour for its historical association with Tagore, who never directed another film, as well as for being a major cultural event in Calcutta of the 1930s—it still remains a partial recovery, far from the 10,577-foot reel of the original.

The film was significant for its all-female cast, although some reports suggest that Tagore might have played a small role himself. They were all students from Santiniketan. (Photograph by Nitin Bose.)

The film shoot was an elaborate event in itself. As Sharmistha Gooptu writes in Bengali Cinema: An Other Nation (2011),

“For five days, a twenty-member New Theatres’ crew, including Subodh Mitra, who became a well-known director in the 1940s, litterateur Premankur Atorthy, and ace technicians Nitin and Mukul Bose, worked with the Santiniketan team. According to Mitra, though the production carried Tagore’s name as director, Tagore himself was present in the studio for a single day only when he recorded the speech delivered on his 70th birthday.”

Still photographs taken on the set by Nitin Bose—who was already a promising young director at New Theatres—remain some of the only materials that can index this complex theatrical/filmic event. The set photograph does not aspire to tell the narrative of the film; its role is to entice the audience with images that can suggest a world of inviting fantasy contained by the film.

Film still from Natir Puja. (Photograph by Nitin Bose.)

As evident in these film stills, there is a difficult ambivalence about the nature of the performance on show. They could just as well be images from a stage production. Even though artificial sets did not always aim for perfect verisimilitude, the production design of Natir Puja and its implication of a flat staged space—often pictured with the steps leading up to the stage left intact—suggest the kind of creative confusion that might have led to its commercial failure. The performances are shown to be in continuity with the stage design, unlike most other film stills that were careful enough to remove any suggestion of an artificial staged space, choosing often to go with blank or absent backgrounds instead as the images could then assume a more detachable quality for the collector/fan.

The stills exemplify the emphasis on devotion and sacrifice in the film clearly, but they rarely make the playful gesture that can involve an absent viewer or fan in the text. Bose’s photographs possess the quality of documentary evidence and serve as worthy illustrations of the important production, but they struggle to leap into the commercial, popular zone of affect that other productions could pull off with more ease.

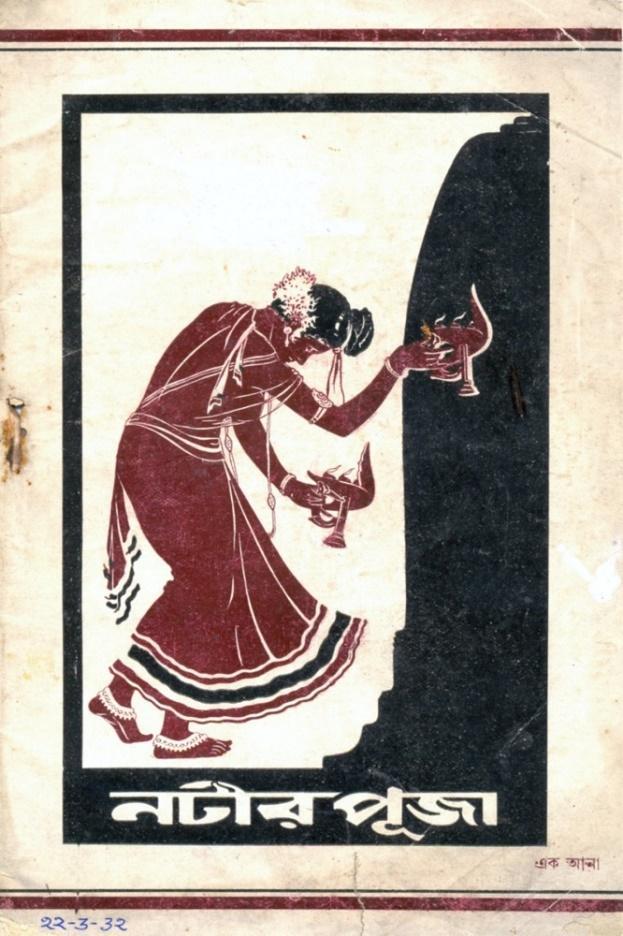

Cover of a chapbook made to aid New Theatres’ publicity plans for the film. It contained lyrics to songs, the text of a speech by Tagore and other material to create a conversation around its production.

To learn more about early cinema histories in India, read Ketaki Varma’s essay on the use of lobby cards for film publicity purposes as well as her two-part conversation with Debashree Mukherjee in the context of her book Bombay Hustle: Making Movies in a Colonial City (2021).

All images are from the private collection of Kazi Anirban. Images courtesy of Kazi Anirban.