Constructing Archives of Community: Srinivas Kuruganti on 1980s California

When Srinivas Kuruganti landed in California from Delhi in 1986, he felt intense exhilaration at his sudden independence. However, the reality of not having a support system was intimidating. So was having to figure out how to have conversations with unknown people, with a different language and accent—even though he was born in Maryland, Washington, DC, and had intermittently spent parts of his childhood there, before permanently settling in Delhi. Hanging out with the Asian community, going out to eat Chinese or Korean food, partying in the dorms and clubbing with the Afghan community led to close friendships and bonds. Most of them had left their homes like him, and they would explore the city together.

In his photo book Pictures in My Hand of a Boy I Still Resemble (2024), Kuruganti creates a narrative of his time in California with his friends and partners. He had begun photographing them with his father’s camera from the 1960s, which he had brought along with him. In a conversation with the author, Kuruganti recalls that at the time of making these images, he was not thinking as a ‘photographer’ and was not considering the images as documentation but a means to relive the past. Unmistakable intimacy exudes through the images, such as in a photograph of a girl posing coyly on a park bench. There is an evident sense of ease with the photographer, whose presence is consistently established. Everyone actually wanted to be photographed, said Kuruganti, which made many images look staged.

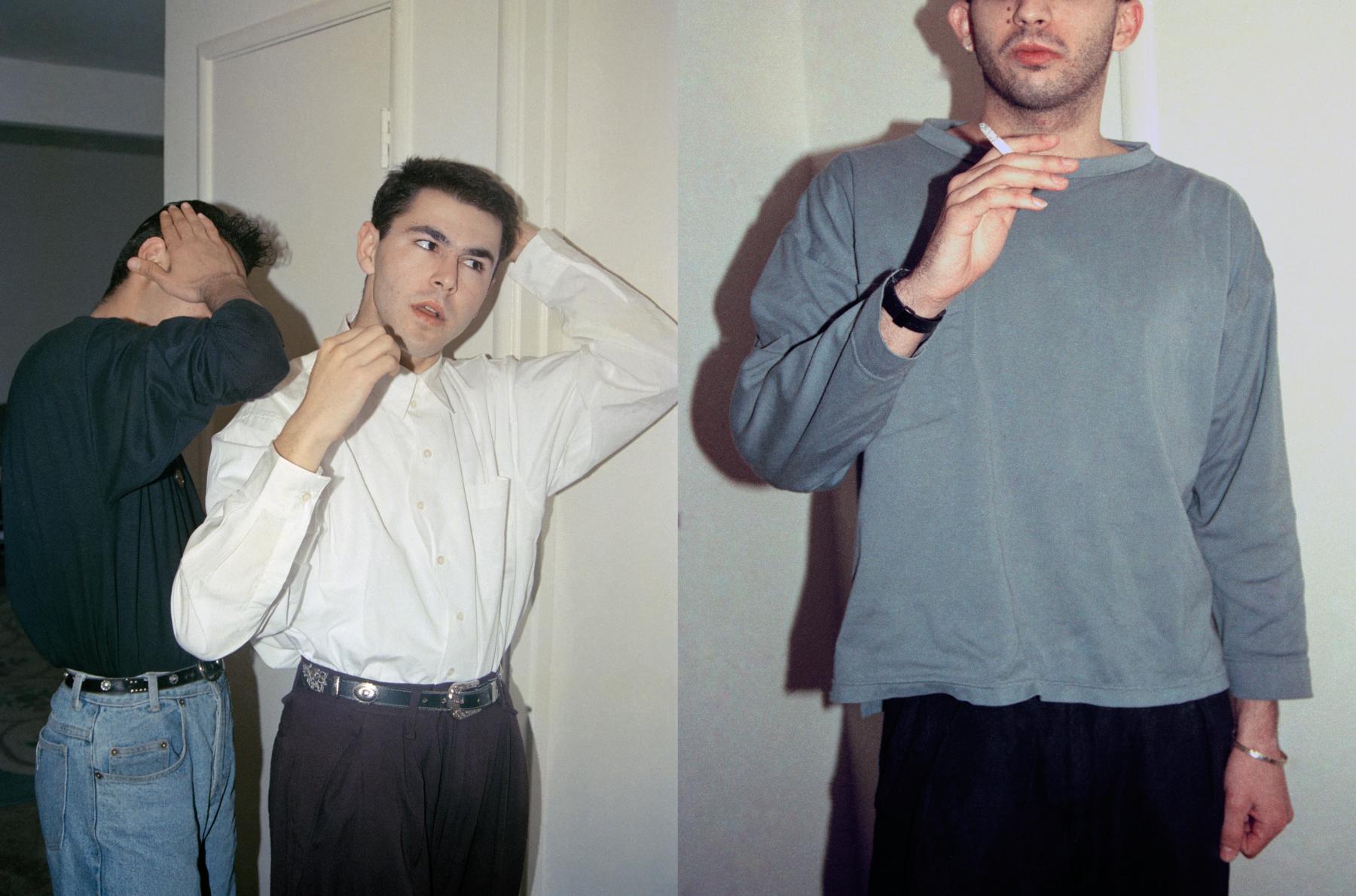

In another image that gives the illusion of having been staged, two of his friends stand as if in the middle of a performance—they were probably styling their hair before going out. Similarly, in another photograph, his friend Mustafa stands on the table wearing nothing but a towel, as if he were being shot for an advertisement or an editorial spread. People were always performing, Kuruganti acknowledged—even he would, when he was being photographed. Editing becomes a significant aspect of constructing the narrative. In the picture above, his friend’s face is hidden. Instead, the photographer foregrounds his friend’s hand as it holds the cigarette—possibly highlighting the reason why a young Kuruganti photographed this in the first place.

With photographs of posters of actors in a friend’s room or leaflets announcing a club night, it almost seems like a personal diary or an album filled with trinkets and paraphernalia. Photography, here, was a collaborative act where the photographed contributed to the act of photographing by performing for the camera. Single authorship is further diluted as some of the images, particularly of the artist himself, have been taken by his friends. A kind of trust that emerges from being together shines through in these photographs. Many of these images actually found their way into the family album maintained by his parents, after he sent some photographs back home. He did not want this book to become a conventional album and decided to fictionalise the narrative. Moving against chronology, he zooms into portions of images, like a friend’s face in a car, to heighten the emotion in the moment of viewing, almost creating an illusion of a film sequence. He also withholds the identity of his friends, thereby leaving a puzzle for the active viewer to play, guess and be confused with.

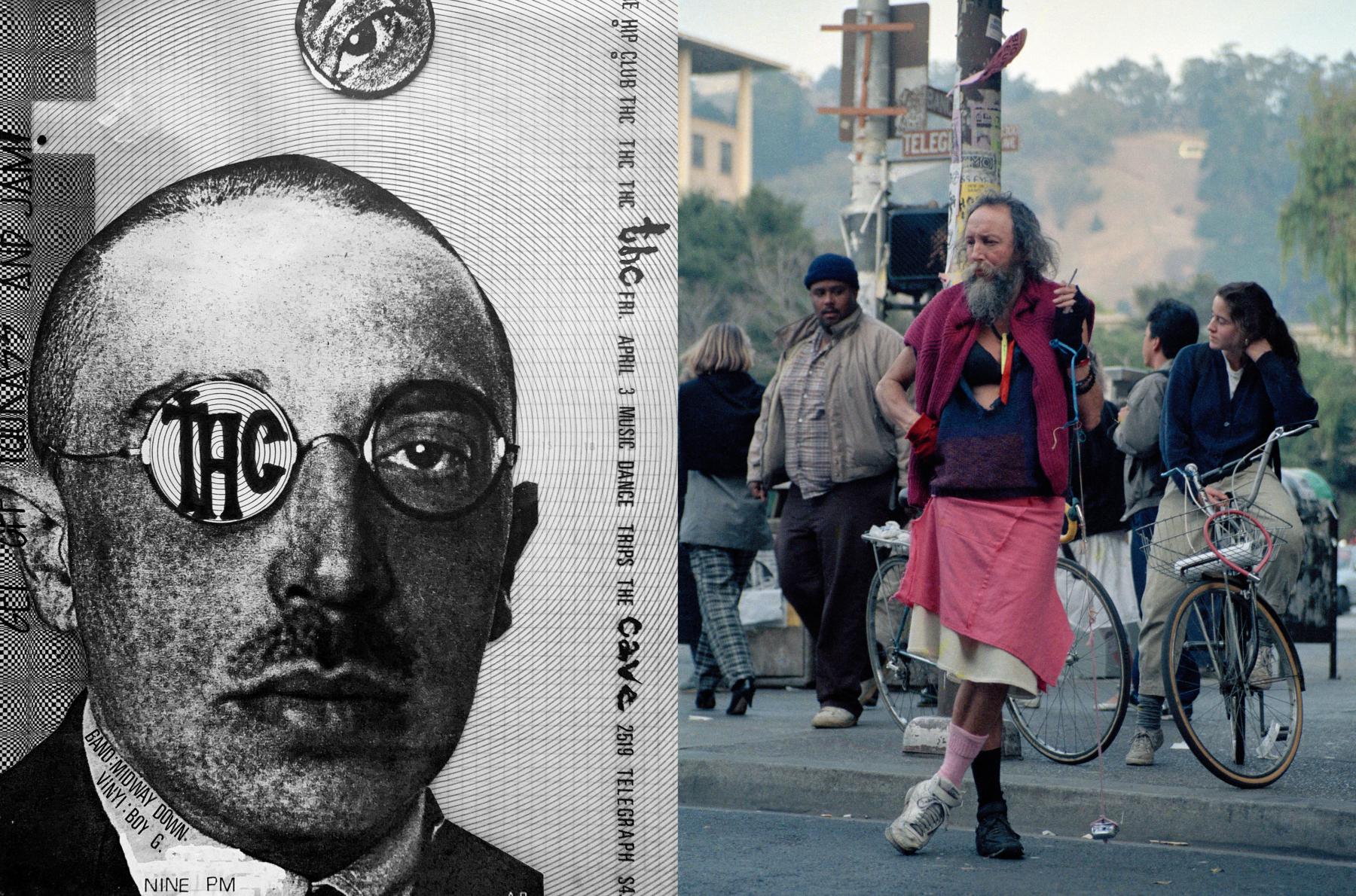

During the 1980s, club culture was thriving in LA, especially in the Eastside, with DJs mixing disco, new wave, pop, reggae and freestyle. Berkeley Square, a club in California that was run by their Vietnamese friend Son Tran, held parties and had live bands. Kuruganti recalls how people would walk down the streets passing flyers for clubs—they could also be found at record stores like ‘Rasputin Records’. This photograph of a poster announces a THC night at Berkeley Square, which was a special night for either a live band or DJing, which their friend Marcel often did. After a friend became a bartender there, it became a place to hang out and get free drinks, while listening to metal, new wave, rock and punk.

Music genres like punk and goth were influencing fashion, which found itself becoming a significant part of youth culture and streetwear—like leather jackets. When Marcel, Mustafa and David started wearing black clothes with interesting shoes and haircuts, Kuruganti was enthralled. He too adopted black clothes, started applying eyeliner and wearing harem pants. The young artist also got quirky haircuts from a Filipino hairstylist—much to the surprise of his family, who were faced with a strange haircut when he would return home. To source their leather jackets or metal studs, the group often went to a Punjabi-owned shop in the Haight district of San Francisco, called ‘Daljit’s’, and Srinivas felt a connection to Sardarji, who ran the shop, who would talk in Hindi to him. He once bought buckled pointed-toe shoes which he is sporting in this photograph, taken by a friend.

The emulsion has come off the negative in the image above, causing this flare. These negatives travelled with him as he moved from California to New York to London to Delhi to Mumbai and finally, back to Delhi. He wanted to highlight the impermanence of a medium which is supposed to preserve time. Here, the man sports an Iron Maiden T-shirt, once again highlighting what music young people were listening to. Surprisingly, he did not take any photographs of Berkeley Square, even though he recalls watching bands like Samiam perform, which later became household names. Kuruganti also watched Harry Dean Stanton perform with his band, before he even knew who the actor was. DV8 was another club in San Francisco where they would go dancing till early morning. For Kuruganti, capturing the intensity of friendship seemed more important.

Going through these photographs after thirty years, Kuruganti wondered what made him take this image of a cabinet of alcohol from one of the dorm parties. The whole affair was a practiced routine: drive to the store and pick up large quantities of cheap alcohol—things permissible within a student’s budget—and return to the dorms. At one of these parties, he got his ear pierced with a thumbtack. Could this image have served as a remembrance of the kind of community nightlife and excess that seemed fascinating to a younger version of him then?

During that time, bikes were becoming part of mainstream culture, albeit predominantly white culture, with Harley Davidson becoming remarketed as everyone’s bike—anyone could own it. When his friend Hansoo bought a 1000cc motorcycle, the two would hit the highway at 120 miles per hour, feeling exhilarated at the risky act and immersed in the aerodynamics of the motorcycle, which made their bodies lean forward. When Mustafa got a road-style bike, they would go out on weekend trips and picnics. The motorcycle became significant to sustaining this diverse community.

This above image is from when six of them took a car trip to Mexico. He must have set up a timer on his tripod, Kuruganti recalled, and it just so happened that David was right in front of the camera. Another figure on the left seemed to have been caught mid-movement, as he rushed to join his friends. Kuruganti captures these moments of serendipity in his images, which highlight the rawness of emotion on an unsuspecting face or the careless abandon in between moments of formally posing for the camera, like the other three friends in this photograph.

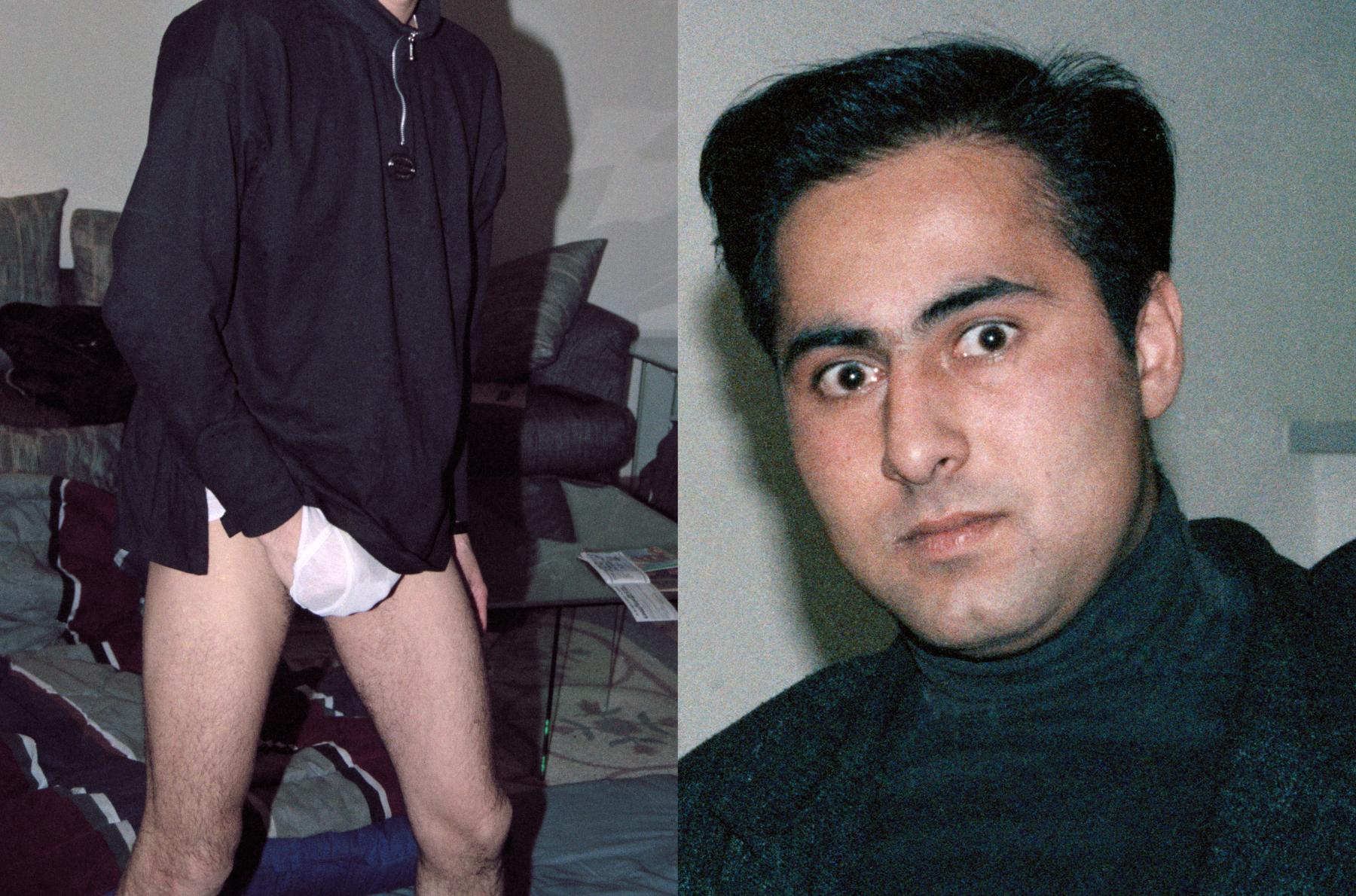

Another way Kuruganti constructs the narrative in the book is through juxtaposition. In this spread, a boy has his hands in his pants (left), while a friend’s scandalised face follows it, once again like a film sequence. Then no one really cared how they were being photographed, Kuruganti recalled. Playfulness is imbibed in the editing and placement, and the original context of the image might be forgotten for us as we are immersed in what Kuruganti wants us to see. For him, looking back does not only mean nostalgia but also amazement at having indulged in risqué and risky behaviour—and not feel ashamed of the lack of self-censorship.

This image is actually a still from a film which Kuruganti made during a slightly darker period in his life. He had dropped out of college and was feeling really lost, caught up in the cycle of working eighteen-hour shifts at Chez Panisse, not making enough money and the sense of temporariness surrounding everything. It was a Super-8 film questioning the idea of being invisible, which perhaps stemmed from a certain stasis in his life. Moreover, being single amidst friends—all of whom had girlfriends—furthered this isolation. Here, he dressed up Mustafa, wrapping cloth around his face—almost like the film versions of ‘The Invisible Man’, as he performed his invisibility.

An extremely self-reflexive image (left), the numbers were given to the negatives after Kuruganti would drop off the film at the lab. It was a shop that sold groceries and everyday necessities like shampoo, but it also had a little counter to get films processed. Kuruganti recalled the excitement of picking up the photographs after they had been processed as everyone would sit with the images and be astonished at what they or he had photographed—he would also give them a copy, although he wonders if anyone had preserved them at all. These images construct a portrait of young South Asian students near and far away from home, at a time in the ’80s when music, club culture and the activities around it were creating a certain community. Uninhibited, Pictures in My Hand of a Boy I Still Resemble captures the joys and the heartbreaks of being young.

To learn more about Srinivas Kuruganti’s practice, revisit Najrin Islam’s two-part conversation with the artist on The Analogue Approach Project (TAAP) and on working with his own archive. Also watch an episode of In Person featuring The Analogue Approach Project.

All images from Pictures in My Hand of a Boy I Still Resemble (2024) by Srinivas Kuruganti. Images courtesy of the artist.