A Satire of Patriarchy: Examining Kathal - A Jackfruit Mystery

Kathal - A Jackfruit Mystery (2023), directed by Yashowardhan Mishra, stars Sanya Malhotra as inspector Mahima Basoor in the hinterland of the Bundelkhand region in north and central India. The film offers a satirical take on the nature of bureaucracy, politics and the police procedural through its insipid and dry humour. Kathal revolves around the theft of two jackfruits—belonging to a exotic variety named “Uncle Hong”—from the garden of MLA Munnalal Pateria (Vijay Raaz). The plot unfolds amidst a village rooted in a prejudiced, myopic view of women, where forty-three missing women are of less concern, reduced to a trivial quotidian story that effaces any investigation and newspaper headlines. However, Mahima ingeniously steers police energy and resources to find the missing girl by directly incriminating her as the thief of the stolen jackfruits.

Vijay Raaz as MLA Munnalal Pateria, talking about the stolen jackfruits dubbed the “Uncle Hong” variety.

The kidnapped girl is the gardener's daughter, who works for Pateria. Her abduction insensitively results in slut-shaming her for chewing tobacco and wearing ripped jeans, which, according to society, is an inherent marker of her disposition and hence subsequent outcome. The mystery of the missing jackfruit ensues in a chaotic search for the kidnapped girl.

In a patriarchal society, men typically dictate the norms and codes of conduct, altering them as and when to suit their convenience. This leads to the codification and expectations of social and personal behaviour, which are strictly monitored to exert and retain control. The protagonist, Mahima, seemingly breaks the stereotypes and gender norms expected of her as a female inspector. However, Mahima subconsciously also inhabits normative expectations embedded in patriarchal structures that society fosters. She eventually succumbs to its forces without ever realising it.

An argument between Mahima and Saurabh, referring to his use of brutal violence. Mahima, as his superior officer, chastises Saurabh, but the scene frames Saurabh’s reaction as mired in his underlying sexism and casteism.

On the one hand, Mahima chastises the woman constable on her team about the domestic labour she is expected to perform; on the other hand, Mahima ruminates on her upcoming promotion in the police force as her love interest, Constable Saurabh (Anant V Joshi), remains her subordinate at work, a fearful realisation of an irrevocable widening gap between them. Saurabh often falls into an ingrained casteist mindset, whether it is beating innocent marginalised poor people at a wedding march or deliberate ignorance to pay heed to a gardener’s complaint about his missing daughter. His redemption arc and Mahima’s constant efforts to bridge the power and social gap between them are lacklustre due to the pervasive intersection of caste, class and gender.

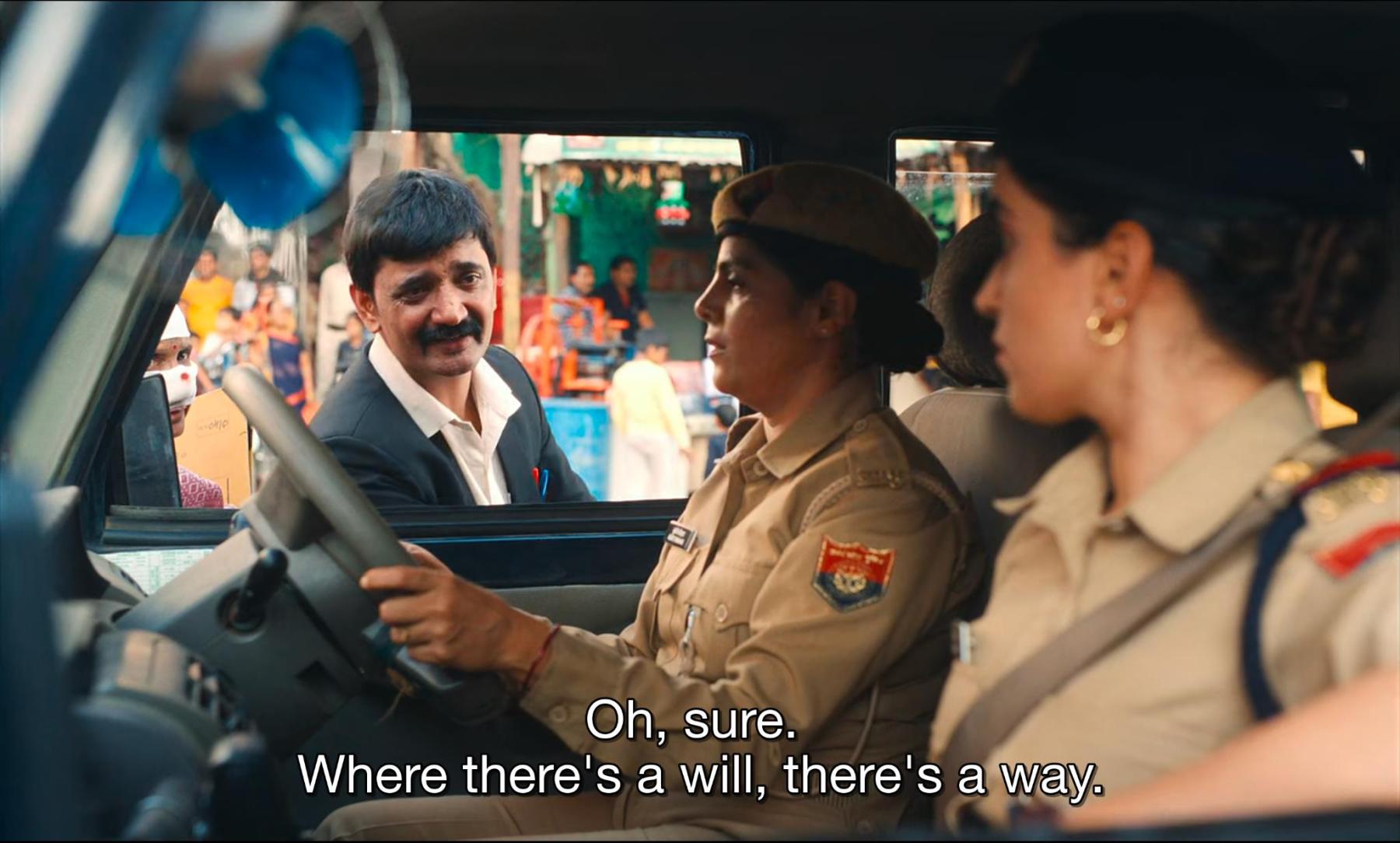

Encounter between Kunti’s Husband and Mahima.

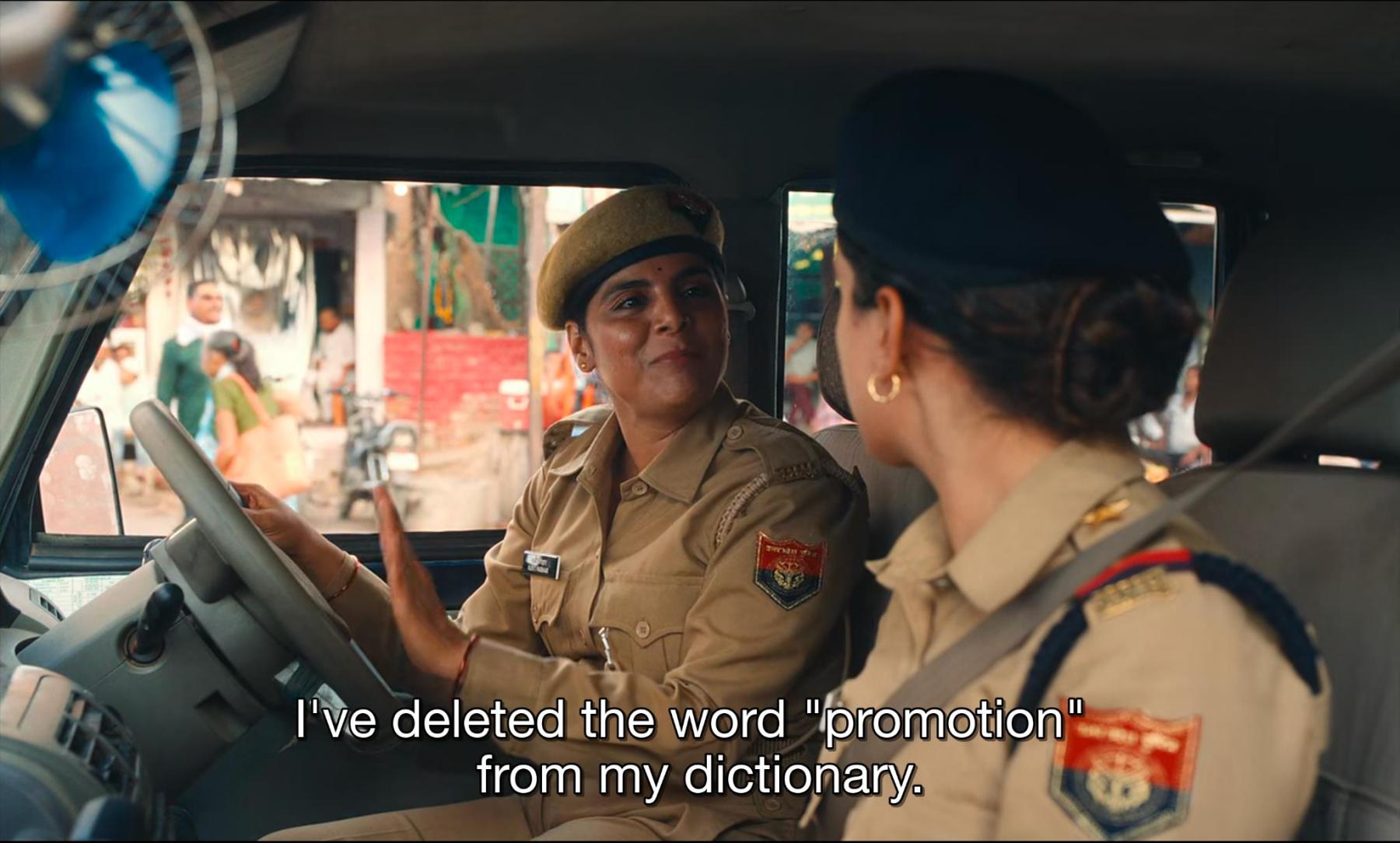

The film makes apparent social hierarchies in the patriarchal system that levies expectations on women, whether in the domestic or work space, despite their position or role in society. Mishra presents the two distinct approaches he sees in the women of the police force through a conversation between Mahima and Kunti in the police jeep. In the scene, Kunti encounters her lawyer husband, who stops their jeep in the middle of the road. He asks Kunti to make aloo bonda (a deep-fried potato snack) for his friends at dinner. Kunti hesitantly asks Mahima if she will get free by then. Kunti’s husband, without even letting Mahima speak, dismisses her by saying, “Hojayega, jaha chah hai waha rah hai. Kyu, madam ji?” (“Of course it will happen; where there is a will, there is a way. Right, madam?”) After the husband leaves, Mahima asks Kunti, “Will you make aloo bonda for your whole life? What will you do after the promotion?” Kunti naively responds, “I will get transferred after promotion, and then who will manage my husband and father-in-law? I have removed the word ‘promotion’ from my dictionary forever.” The film seems to suggest Mahima’s transgression through Kunti’s submission to the gendered division of domestic labour. Despite being embroiled in a high-stakes investigation as a part of her duties, Kunti has to make time to cook food and entertain her husband’s friends.

Kunti acts as a foil to Mahima, embodying a submissive approach to her family and not harbouring any ambitions for her job.

Another scene towards the film's end shows a wall painting of Mahima with the inscription Naari-Sammann, Police ka Abhiyan (Women Power, a Campaign by the Police). The senior officers ask Mahima, “Do you recognise her?” To their dismay, she says she does not. They laughingly tell her, “It is you!” The scene's humour lies in the fact that the painting does not remotely resemble Mahima. It points towards the emptiness of ‘social justice’ campaigns that claim to be working towards empowerment while at the same time subtly removing them from the centres of power or anything that makes them clearly distinct.

The scene places its humour in the visual representation of ‘tokenism’, where a female police officer that does not remotely resemble Mahima in any way is referenced as such by her male superior officers.

The film’s narrative is layered with the everyday casteism that is inherent in the Bundelkhandi society, which forms the crux of the film. From Saurabh’s father making comments alluding to Mahima’s caste identity, calling her ‘Basoran’ to the constable Mishra ji, a Brahmin, who chastises Saurabh for letting Mahima scream at him. MLA Pateria reacts viscerally when Mahima, following up on the jackfruit investigation, steps on his carpet. The incident is immediately followed by his proclamation to "sprinkle gangajal" (water from the Ganga). Constable Mishra’s hypocritical nature is evident in his anxieties around his daughter’s marriage. As an upper-caste Brahmin, Mishra wants another Brahmin man for his daughter. He is willing to pay dowry and flaunts his daughter’s picture to Saurabh while remarking that she wears jeans and shirts and is completely subservient.

From the opening scene of the film, showing a slogan against casteism by promoting education, health and values.

Yasowardhan Mishra carefully stages cellphones as a central plot device in this political wild goose-chase turned manhunt. The gardener’s cell phone is found in the MLA’s yard, which leads to him becoming a suspect. The kidnappers’ location is extracted by the cyber cell and a subsequent visit by the police to a spectacles shop. It is omnipresent, from being the vessel through which senior officers dictate orders to Mahima to the sinister ways orders “from above” are conveyed through phone calls, causing the imprisonment and release of people at the will of those in power. These intangible movements of influence are a direct jibe at the fallacy of law and order. Nevertheless, the film’s satire lingers when we realise the gardener’s cellphone is costlier than the ‘kathals’ the police suspect him of stealing. The story culminates in a court sequence. In the penultimate scene, Mahima declares that while jackfruits can be grown again, the girls who are taken away never return to their homes.

Subtle placement of a news ticker when Pateria threatens to burn the SP’s office if the jackfruits are not found.

A Dalit protagonist like Mahima Basoor is a rarity in most mainstream Hindi cinema. However, the film fails to delve deeply into structural complexities and address the systematic discrimination faced by marginalised people. Mahima is subject to casteist comments and patriarchal subjugation despite upholding a prominent position in the police force. The narrative, with its superficiality in dealing with caste issues, never brings forth her identity as a Dalit woman, which places her at the intersection of caste and gender oppression. The light atmosphere of the film, with its antics and jibes, reduces the urgent pressures pertaining to structural reform into cheap humour catering to the upper-caste audience. The incompetent police force with dominant upper-caste individuals such as Mishra, who perpetuates caste-based aggression, is reduced to a thoughtless and doltish character for entertainment. It misses the opportunity to comment on existing biases within law enforcement. The tokenistic approach and such trivialisation of struggles faced by marginalised people often lead to stereotyping and prejudices subject to further discrimination and violence. The film holds the risk of maintaining the status quo where such discrimination is seen as incidental rather than integral to social structures.

To learn more about the intersectional representation of caste and gender, read Ankan Kazi’s reflections on Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh’s Writing with Fire (2021), a walkthrough with Supriya Dongre at the Serendipity Arts Festival (2022) and Arushi Vats in conversation with Diwas Raja Kc on Dalit: A Quest for Dignity (2018).

All images are stills from Kathal (2023) by Yashowardhan Mishra, courtesy of the director.