Archive of Absurdities: Abstraction, Waste and Sonic Memory

I was reading Khaldun’s Muqaddimah, and it struck me that the warfare economy’s tendency of running away is the opposite image of Khaldun’s ideal of nation-building.

- Aziz Hazara (AH)

Aziz Hazara’s second solo show at Experimenter, Muqaddimah, presents a series of contradictions as a way of insistence on viewing the war economy’s technologies of control along with its waste. The artist makes a satirical comment on contestations of power while simultaneously telling stories of the landscape of human suffering in Afghanistan. The first part of this essay grapples with his quest to depict the profit motive of the military-industrial complex and the afterlives of war objects by juxtaposing the transformation of everyday objects into instruments of war and the trajectories of militarised technologies as they are rendered into waste. This essay follows Hazara into the next set of contradictions to ask, at what point does war become infeasible? As the ongoing genocide of Palestinians and recent Israeli invasion of Lebanon exemplify—sustained as the conflict is, and invigorating of the same war economy that tethered America to Afghanistan—the decision for military withdrawal, or rather for an imperialist power to flee from the land it occupied, is not when the human cost is too much. And what happens when the occupier leaves? Does the morning after mark the end of war?

.png)

Kite Balloons (2016).

Occupation has its own logic of “loot”—governed by an ever-expanding post/neo/colonial capitalist regime of accumulation and dispossession—that structures contestations of power and pervades the affective fabric of the society in which it operates. In Kite Balloons (2016), Hazara’s still image of the gigantic aerostat radar systems that floated above Kabul, Kandahar and other Afghan cities from the early 2010s serves not only as a document of wartime surveillance practices, but also of the perpetuation of a culture of “loot,” of plunder and abandonment. Thus, when the Americans evacuated in 2021, an act Hazara repeatedly calls, rather aptly, تماشا (tamasha, or a drama), they left these technologies of surveillance in the sky—now, no longer of use to them. These technologies, now abandoned, precipitated a looting contest amongst Afghans to grab hold of whatever was available, waiting to be integrated into a thriving waste economy.

UNHCR Tent.

If Hazara’s photographic intervention documents objects left over by every successive imperialist regime as symbols of waste, his attempt, as he says, is to demonstrate how occupation never leaves. Speaking of the Soviet tanks, which continue to occupy space in every neighbourhood as literal reminders of the continuing presence of the occupier long after they have left, American drone warfare with its sophisticated technologies, has, he emphasises, its own economies of memory. For, recyclable militarised objects—leftovers from both Soviet and American wars—stripped off their original function as instruments of war-making, are now rendered waste. But they re-enter the Afghan economy, he explains, through black markets where they are sold at deflated prices. For instance, a UN tent worth $100 can now be found at a mujahideen bazaar for $5. In other instances, they are transformed into everyday articles, like a masala dabba (spice box), constituting tangible archaeologies of civilian lives.

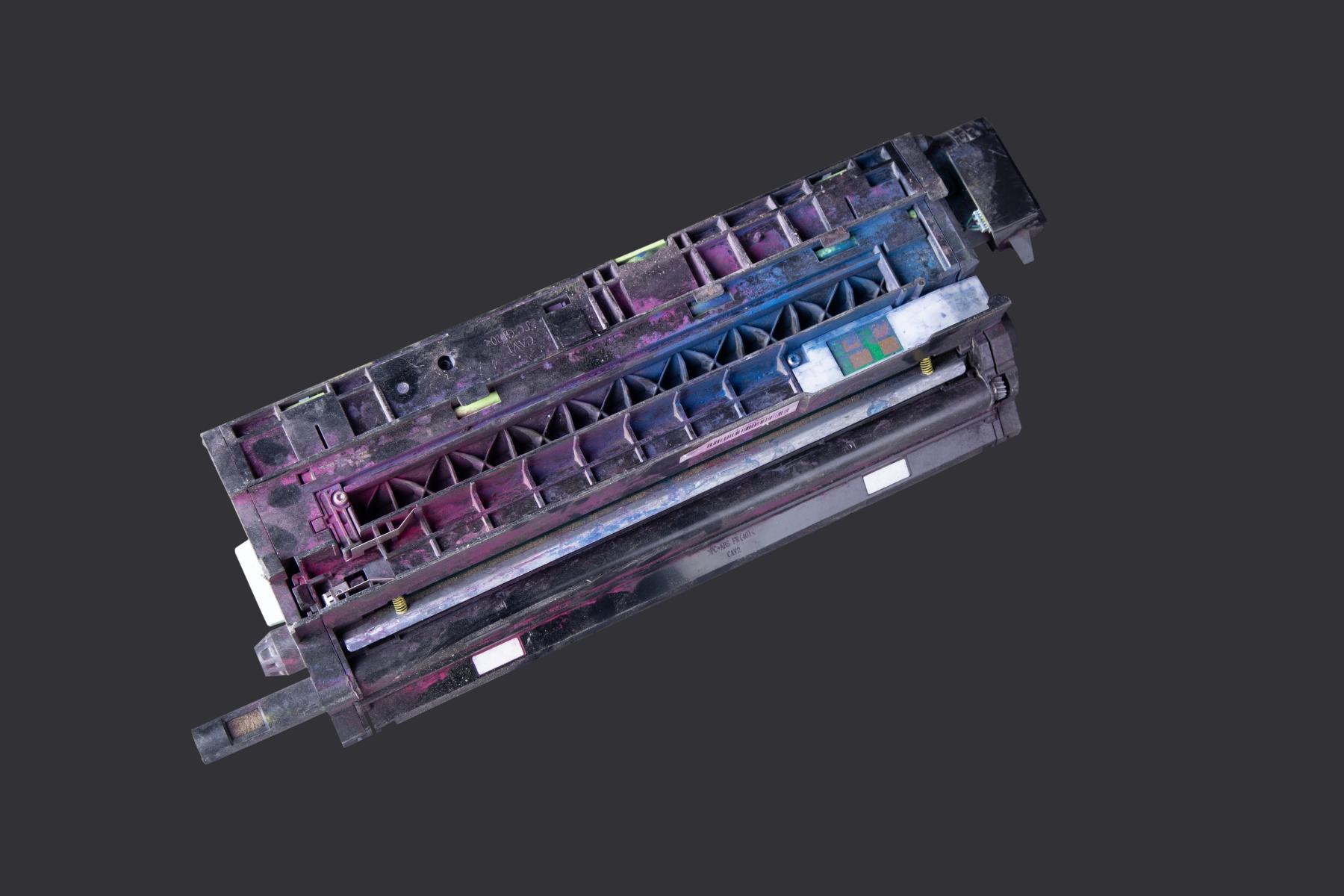

Untitled (Bagram) (2024).

The juxtaposition of Bushka-Bazi (2023) with Untitled (Bagram) (2024) as we saw in the first part of this essay—of the sonic landscapes of struggles for political power with material cultures of waste, and of political regimes governed by the profit motive with Khaldun’s concept of عصبيّة (asabiyyah), or social solidarity—sharply and evocatively speaks of the reduction of Afghans to that of waste. Their presence becomes necessary to sustain the war economy, which is precisely why, in the logic of capital, they are rendered dispensable.

.png)

Untitled (2016).

War detritus is not only what is left behind; it is also what is recycled, feeding into the making of contemporary Afghan society. Is waste then not only the abandoned material objects but the transformation of Afghan society and its people into the backyard of colonial powers? As Hazara points out, with American arms-manufacturing companies photographing weaponry against the skies of Afghanistan—a marketing strategy so they can sell their products to others participating in the military-industrial complex—does the Afghan landscape also serve as raw material for perpetuating further cycles of profit-making for capitalist wars in recurrently expanding new zones of conflict?

Abstraction is a double-edged sword.

- AH

.jpg)

Dialectic (2016/2024).

Dialectic (2016/2024), a pair of video installations, is yet another exposition of Hazara’s penchant critique of both war and the tropes of Western corporate media’s representation of suffering. In a nation that has gone through three regime changes in the last forty–fifty years—in the 1990s, 2001 and 2021—every time there is a transition from one regime to the next, Hazara says, there is a period of four or five days when nobody knows anything. The film, placed in the centre of the room, is then an “archive of absurdities” within warfare, marked perhaps by the image of Santa Claus amidst a portrait of everyday life in a warzone, momentarily suspended.

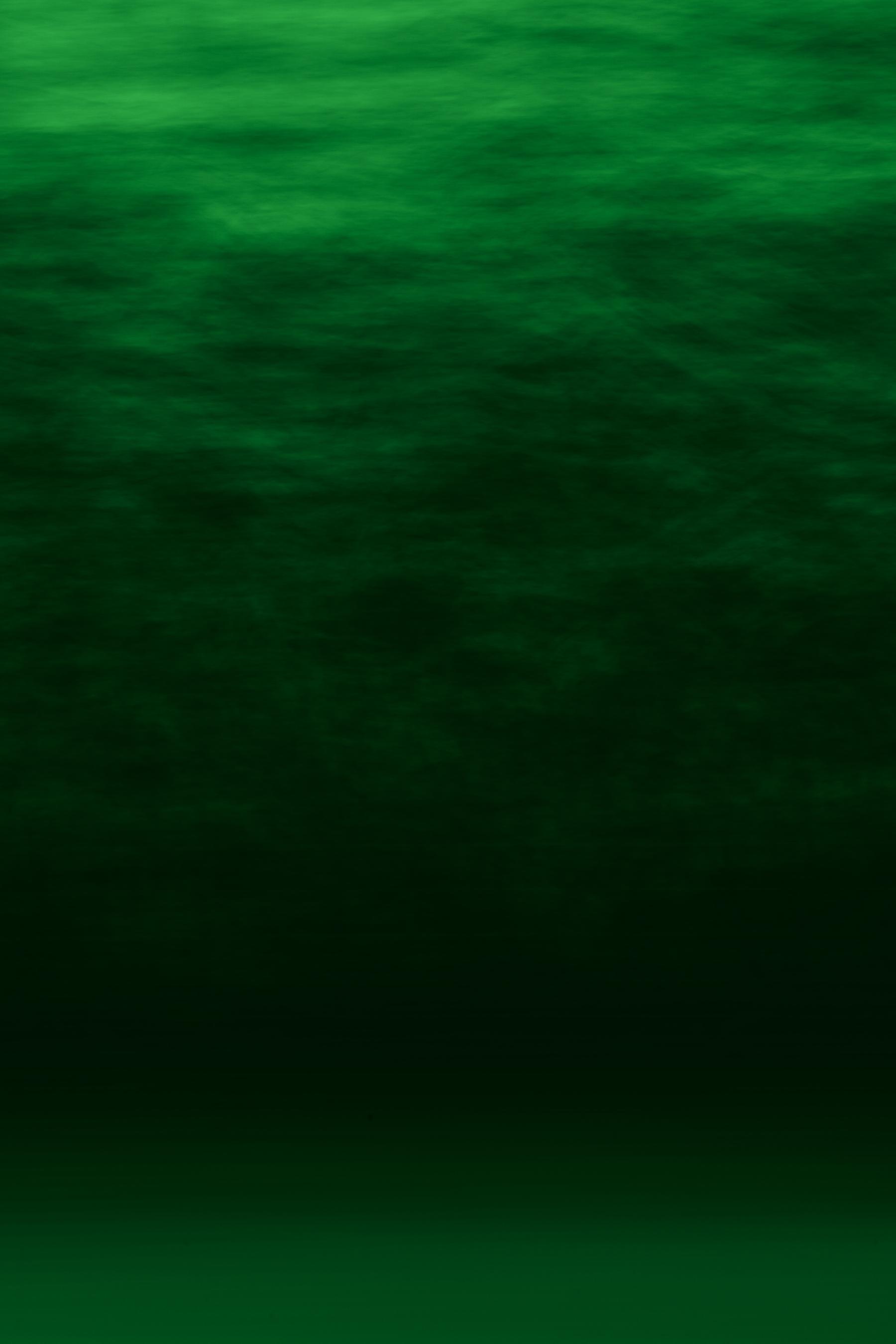

.jpg)

Installation view of Dialectic (2016/2024).

Set against it, on a larger screen to the right, is a green-tinted video made with a military night-vision camera that American soldiers used in low-light situations, or night raids during which suspects were targeted in the dark and sent to a detention area on a military base, without knowledge of their families, considered by many as worse than air raids. An extra-judicial attack with high levels of civilian casualties, this military tactic has parallels with the Israeli Defence Force’s strategy of “walking through walls,” where the city is not only the site but also the method of warfare, decimating the population from the inside out.

A British colonial officer stationed in Punjab said of the Pathans in the Khyber-Pakhtun region, they are masculine, brutal, fanatic; mullahs, saints and devils all at the same time, they are the most dangerous people in British India. This colonial gaze continues, constructing Pathan male bodies as uncivilised and from whom the women need to be liberated.

- AH

Interspersed with footage filmed by American soldiers—which obfuscates the humanity of Afghans by turning them into objects of dangerous masculinity and renders the lands they inhabit in need of control—Hazara’s video is a poetic gesture towards sensory memory and love of one’s homeland. In so far as it encounters and attempts to converse with nature in its vital form, it offers an internal critique of the colonial gaze and its abstraction of the Afghan subject and landscape. At the same time, it also abstracts from the perilous everyday images of war, which already finds critique in Hazara’s record of moments of absurdity in the transitional periods of occupying regimes. Even as both video installations contain specific dramas of internal juxtapositions, it is in the placement of these two films—the illegible abstract perpendicular to and engulfing the legible concrete—that Hazara reveals once again, a cascade of layered contradictions, that consistently offer critique, without resolution.

What is one abstracting? There is a power relation between the abstracted and the one who abstracts.

- AH

Moon sighting (2024).

If Hazara’s images of waste objects against plain black backgrounds—Untitled (Bagram) (2024)—serve as a critical abstraction of the modalities and leftovers of war, his concerns remain focused on political action. “If one were to show how modern warfare was making money, one needs evidence,” he says, in a brutal reminder of the burden of proof in international law. Moon sighting (2024) captures the moment of explosion of a Kamikaze, when “everything becomes abstract, everything is falling apart. While it is evidence of a strike and its aftermath, it looks like evidence but does not read like evidence.” It is an archaeological site—"half-image, half-document” insofar as “nothing makes sense, nothing is readable; it acts as a testimony of the occupation.”

کابل تو ہمارا شہر ہے

(Kabul toh humara sheher hain). We know its every corner.

- AH

.jpg)

Rehearsal (2020).

Returning to the question of sound, I ask Hazara about Rehearsal (2020), where a young boy, standing on the shoulders of another, imitates the action of soldiers firing American M-15 military rifles. “The question is one of memory,” the artist says as the sonic memory of warscapes become carved in one’s habitation and imagination of home.

“Kabul is no longer the city it once was. Home is a romantic junkyard,” he laughs. Before gently reciting the Pashto proverb,

“هر کس را وطنش کشمیر است.

“(Har châta khpal watan kashmir de)

“For everyone, their homeland is as beautiful as Kashmir.

In case you missed the first part of this essay, read it here.

To learn more about the representation of conflict in Afghanistan, revisit Najrin Islam’s essay on the feminist lens of Roya Sadat and also a two-part conversation with Miriam Ghani on recuperating the documentary archives of Afghan film. Also read Radhika Saraf’s two part essay on Samira Makhmalbaf’s At Five in the Afternoon (2003).

All works from Muqaddimah (2024) by Aziz Hazara. Installation views photographed by Abner Fernandes. Images courtesy of the artist and Experimenter.