Art in Delay, Hesitation as Film: Maisam Ali’s In Retreat

In Retreat (2024) was the first Indian feature to have its world premiere in the Cannes ACID sidebar. It had its Asia Premiere last week at the Busan International Film Festival.

Maisam Ali's In Retreat (2024) is an itinerant’s tale. Its unnamed protagonist (Harish Khanna) has been away from his mountainous home in Ladakh for years. Now back in town, we see him almost always on the move—on buses, in cars, on foot. Vignettes of different lives—a family in mourning, a couple’s quarrel, a roadside drunk’s spirit-fuelled singing—play out through open windows and on the narrow streets outside as the protagonist roves constantly. A witness to each episode and yet never fully part of any one, his fleeting involvement with each story seems to be a way of putting off participation in his own. His perpetual state of wandering in the film then becomes a metaphor for his inability to stop; a pause that would have allowed, presumably both in the past and in the present, the possibility of a return home. His roving becomes his way of deferring the moment of return. To pause is to confront a reality he seems bent on avoiding.

Maisam Ali.

Moments into the film, as he sits inside a bus, lulled to sleep by its movement, a sequence that slowly culminates in a reveal of the film’s title against a pale evening sky becomes Maisam Ali’s lyrical expression of his film’s central concern. As the music swells, the camera’s focus gently shifts from the passenger’s languid face to the passing landscape outside his window, the move underscoring the setting of the bus and the itinerancy it represents. The voice-over that fills in for his silences throughout the film articulates the traveller’s dream: of an endless road that allows an escape from one’s stories, a perpetual delaying of tomorrow. Ali’s debut feature is about—and also effectively is—its character’s act of deferring, suspension turned to art. In Retreat essentially materialises in the space and time between the two shots of its protagonist standing before his house. The first occurs in the opening minutes of the film as someone inside the house can be heard expounding the value of those who are present through both good and bad times, and the second at the end of a long night spent on the streets. Contained within these parenthetical appearances is the bulk of Ali’s film, which follows its character on his procrastinatory wanderings around the town. In Retreat becomes a document of his hesitation. It is the forever-lengthening road of the nomad. It is reluctance in film form.

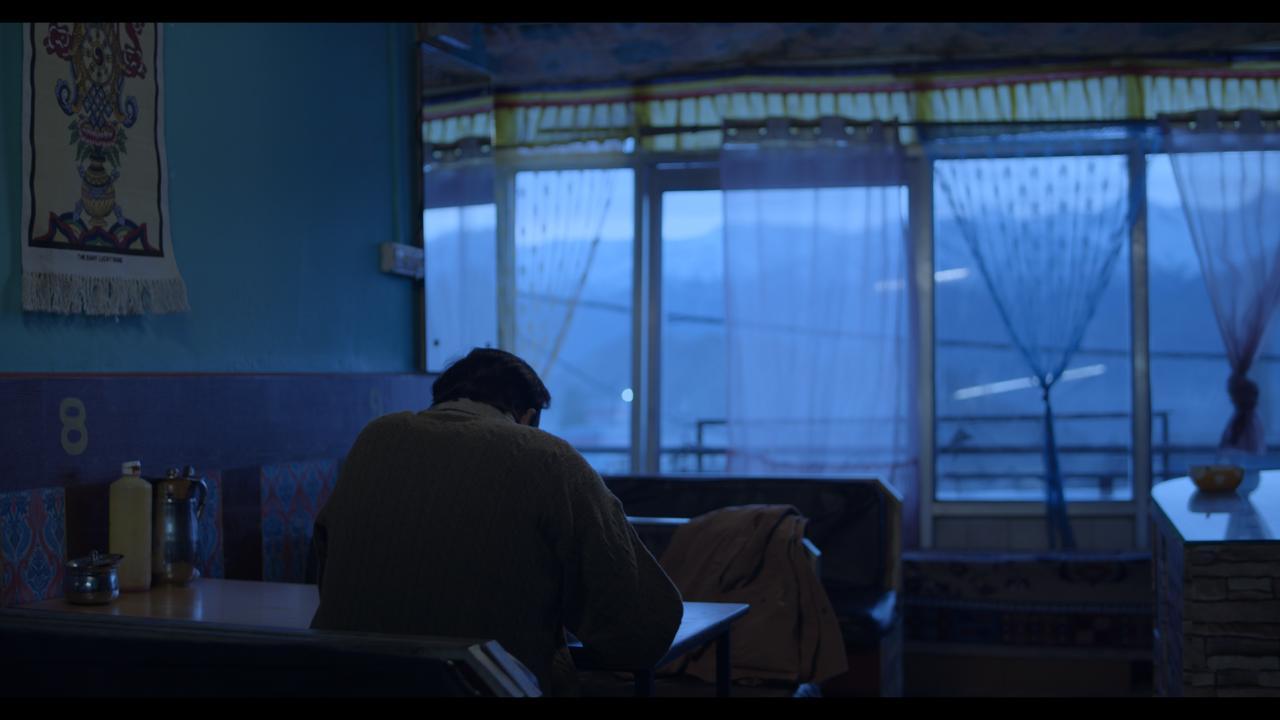

Instead of the instantly recognisable views of Ladakh’s famed beauty and majestic mountains, in Ali's film, the blue hills, when visible, are mediated through moving bus windows or the frayed curtains of a dingy eatery, as in the still above.

In Retreat eschews specifics—we know nothing about why the protagonist had to leave home, where he has been all this while and why his homecoming is so fraught with sadness. Instead, dwelling on a man’s absence at his brother’s funeral and reluctance to face his family afterwards, the film turns into a languorous, melancholic and occasionally even guilty meditation on universal themes of belonging, freedom, home and acceptance. Moreover, in a film where most details remain unknown, the native-turned-‘outsider’ figure—who struggles both literally and figuratively to communicate with people from his own land and is made to feel like a stranger in his home and community—transcends his immediate surroundings to carry echoes of larger, pervasive and global crises around land, rootedness, identity and outsiderhood. Reports of Palestinians forced from their homes, of the displaced thousands attempting to return to northern Gaza only to come under Israeli fire, of Israel’s demolition of Palestinian homes, lives and infrastructure in the occupied West Bank and of Palestinians who have lived their entire lives in refugee camps yearning for a return to their homeland inevitably fill in the spaces left open by the invisible, unstated boundaries that obstruct In Retreat’s character’s own homecoming. The fraught meanings of terms such as home, loss, borders, displacement and return offer ways to blur distinctions between reality and fiction.

A still from Maisam Ali's In Retreat (2024).

The film’s underlying gloom douses it in cool blues and purples. Gone are the instantly recognisable views of Ladakh’s famed beauty and majestic mountains long favoured by filmmakers. Often shrouded in the darkness of the night, the blue hills, when visible, are mediated through moving bus windows or the frayed curtains of a dingy eatery. The rare clear view, on the other hand, is fuss-free and matter-of-fact, its pristineness more often than not slashed by electrical cables and wires. Similarly, in place of an identifiable expansive landscape, we are shown crowded marketplaces, narrow alleys and cramped buses. Apart from pointing to an obvious reluctance to present picturesque shots, and indicative of a local’s familiarity (Iran-born Ali spent the formative years of his life in Ladakh), these views of the region also serve to diminish their identifiability and therefore specificity in the popular imagination. By consistently and consciously taking away these details, Ali seems to insist on making a universal film, of telling a story that could be anybody’s and anywhere. Ali, a Shia Muslim from a Kashmiri trading community that eventually settled in Ladakh, has spoken both of the influence on him of a Ladakhi Buddhist sensibility and of Iranian cinema, especially of the films of Abbas Kiarostami. Ali’s film, with its penchant for quiet contemplation as well as roving disposition carry echoes of those influences. Yet, in his portrayal of everyday ordinariness, the debutant filmmaker has pursued a singular artistic vision; the film is gentle and with a lack of judgement, it is poetic, minimalist and ambiguous.

Iran-born Ali spent the formative years of his life in Ladakh. As a result, the film is imbued with an insider's vision and sense of familiarity.

Adding to the film’s relatively unconventional representations of Ladakh are its repeated shots of a hand sketching the mountain town’s terrain, houses and people. Of the things it meticulously draws is a funeral procession, presumably the one the film’s protagonist as well as its viewers—we—didn’t see. Once the film has indulged its central character’s desire for avoidance, becoming in effect a record of that avoidance, it is as if it cannot hold within its own form the event he has so deliberately missed. It remains loyal to his response; to slip into the past (say, through a flashback) to show us the funeral that he has chosen to be absent from is not only to break the alliance it has shared with him but also to show him up for his non-attendance. The burden of representation of such an event then must fall on another medium (drawing). Art perhaps attempts to assuage a guilt the film itself cannot relieve its protagonist from.

In Retreat was the first Indian feature to have its world premiere in the Cannes ACID sidebar. It had its Asia Premiere last week at the Busan International Film Festival.

To learn more about films set in Ladakh, revisit Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Achal Mishra’s Ri (2023), and to read on films set in Himalayan mountain regions, see Ankan Kazi’s reflection on Keljang Dorzee’s Why is the Sky Dark at Night? and Shranup Tandukar’s essay on Rajan Kathet and Sunir Pandey’s documentary Dhorpatan (No Winter Holidays).

To read more about Indian films traveling to Cannes, you can also read Najrin Islam’s essays on the structure of feeling in Payal Kapadia’s oeuvre, and on A Night of Knowing Nothing, which won the Golden Eye Award for Best Documentary at the 74th Cannes Film Festival.

All images courtesy of Varsha Productions.